Strong employment dashes hopes of year-end interest rate cut

There are two reasons why central banks cut interest rates – ability and need. Australia’s exceptionally strong employment report for September all but eliminated the need.

Australia’s strong employment data has all but dashed hopes of a rate cut by year-end.

With employment growth reaccelerating and the unemployment rate rising only slowly in response to a record-high labour force participation rate, there’s no overall need for the Reserve Bank to cut interest rates. The onus is squarely on upcoming inflation reports.

Put another way, it would be irresponsible for the RBA to cut rates while the economy is strong enough to easily soak up new entrants to the labour force – propping up aggregate demand – and the inflation rate remains well above the 2-3 per cent target band as it has been for three years running.

The RBA looked to have given it some optionality by backing away from its hawkish rhetoric since August, but any hope of a rate cut in the near term was always going to be predicated on data.

After a dovish speech on inflation expectations by RBA assistant governor Sarah Hunter on Wednesday, the money market was fully priced for a 25 basis point rate cut by February.

But after the jobs data, market pricing implied only a 72 per cent chance of a February rate cut.

The RBA has forecast that the unemployment rate will average 4.3 per cent in the September quarter and 4.4 per cent for the rest of its forecast horizon. Those forecasts see the annual growth rate of the wage price index fall from 4.0 per cent to 3.3 per cent, but only get underlying inflation back to the target band by the end of 2025 assuming relatively-low labour productivity growth.

The RBA believes the official cash rate to 4.35 per cent is “restrictive” versus the bank’s theoretical estimate of “neutral” – around 3.5 per cent – but it’s not doing much damage to the labour market.

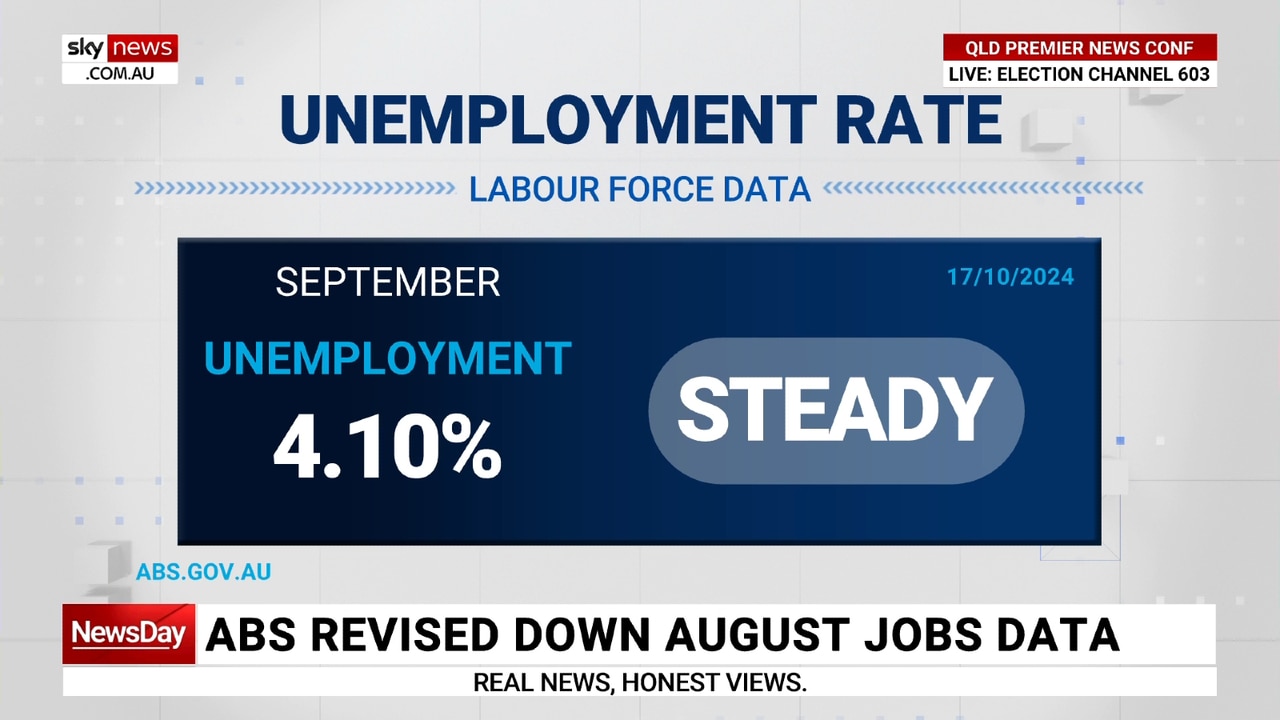

After rising steadily from a 50-year lows of 3.5 per cent in late 2023 to a two-and-half year high of 4.2 per cent by July 2024, the unemployment rate fell to a downwardly-revised 4.1 per cent in August and remained there in September.

Indeed, the jobless rate looks to have stalled around 4.1 per cent since January because of strong employment growth, even as the labour-force participation rate has soared from 66.5 per cent to a record high of 67.2 per cent in the same period.

Seasonally-adjusted jobs growth of 64,000 was almost 40,000 more than expected by economists.

Almost 52,000 of those jobs were in the full-time category that tends to be more durable.

With jobs growth exceeding consensus estimates for six months running, the annual rate of jobs growth has reaccelerated from 2.1 per cent in May to 3.1 per cent, the same level as February.

Capital Economics said the “red hot” jobs market precludes a year-end rate cut by the Reserve Bank.

“With job creation having continually surprised on the upside over the last few months, employment growth in September stood at 3.1 per cent year-on-year,” Capital Economics Australia and New Zealand economist Abhijit Surya said.

“Not only does that represent a marked acceleration from a recent trough of 2.2 per cent in May, it also means that employment growth is all but guaranteed to overshoot the RBA’s year-end forecast of 1.9 per cent.”

In other signs that the labour market is firing on all cylinders, hours worked rose for a third consecutive month to be 2.4 per cent higher than a year ago. Meanwhile, the underemployment rate fell to 6.3 per cent and the underutilisation rate fell to 10.4 per cent.

A composite measure of job vacancies monitored by Capital Economics also rose in September, and while still pointing to unemployment gradually approaching 5 per cent over the coming months, the risks were “clearly tilted towards the labour market loosening at a much slower pace”.

“Overall, today’s labour market data will only reinforce the RBA’s view that labour market conditions are still tight relative to full employment,” Mr Surya said.

Betashares said Australia’s strong employment report left the RBA’s decision over when rates would be cut crucially dependent on how quickly inflation falls.

“Today’s employment report does not rule out rate cuts, though it does rule out near-term rate cuts due to an overly weak economy,” Betashares Capital chief economist David Bassanese said.

“The RBA will be comforted by this report, as it implies it can continue to wait for a decent decline in inflation before cutting rates, rather than being forced into cutting rates due to weakness in the economy.”

He said Australia now faced the prospect of eventual rate cuts for “good” reasons rather than bad reasons – which boded well for both equity and bond market returns over the coming year.

However, the ASX 200 share index shied off a record high after the jobs data as bond yields spiked.

The policy sensitive 3-year yield rose as much as 8 basis points to a 2.5-month high of 3.84 per cent. The Aussie dollar bounced from a five-week low of US66.58c to a two-day high of US67.10c.

Mr Bassanese still thinks the RBA will be able to cut rates by February next year, provided the next two quarterly CPI reports confirm a downtrend in underlying trimmed mean inflation.

But annual trimmed mean inflation by the December quarter CPI report in late January will need to have fallen to 3.5 per cent or less, from the current rate of 3.9 per cent for the June quarter.

However, Mr Bassanese saw a growing chance of rate cuts as early as November or December, if the faster pace of declining inflation in the recent monthly CPI reports continued. In the past three months, annual trimmed mean inflation in the monthly CPI fell from 4.4 per cent to 3.4 per cent.

“At this pace, annual trimmed mean inflation in the monthly reports could be within the RBA’s 2-3 per cent target band by the October monthly report due on 27 November – opening up the tantalising prospect of a pre-Christmas rate cut at the 9-10 December policy meeting,” he said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout