That means if the labour and goods shortages boost inflation substantially then the current efforts by the Reserve Bank of Australia to keep a lid on interest rates are likely to fail. And that’s what the bond market is predicting. Any such failure will cause an interest rate squeeze on highly leveraged home borrowers. It is an indictment on our regulators that Australia has been allowed to fall into such a precarious position.

Our banks and the institutions who demanded higher profits also share the blame. The interest rate squeeze danger comes when banks are highly leveraged on home loans so if there is a default on, say 3 per cent of their home loans, it would destroy 30 per of the capital of some banks.

While the above are my conclusions, they come from a remarkable canvas of research produced by one of Australia’s top banking analysts, Matthew Wilson of Evans & Partners. I have selected three graphs that Wilson has prepared that graphically tell the tragic story and illustrate our vulnerability to the current shortages of goods and labour.

When interest rates are low then theoretically borrowers can afford larger and larger loan to income ratios. In the UK the regulators recognise that interest rates can rise so they stipulate that no more than 15 per cent of a bank home loan book can have a loan to income ratio greater than four and a half times. In Ireland, which was taken to the cleaners in the Global Financial Crisis, they stipulate that no more than 20 per cent of a bank housing loan book can have a ratio greater than 3.5 times The benchmark loan to income ratio is three times.

According to Wilson, in Australia a mammoth 65 per cent of home loans are above four times income and 22 per cent are above 6.5 times — many recent loans are around the 6.5-7 times level.

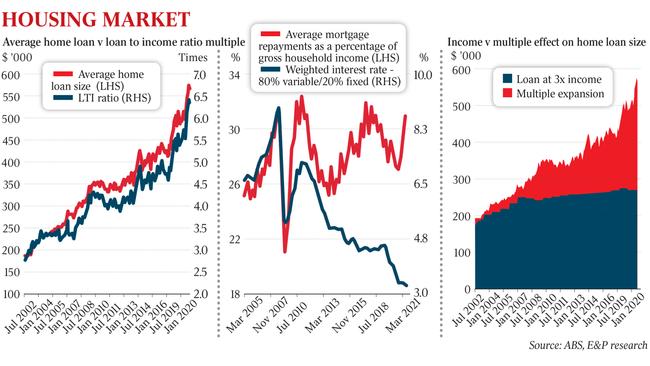

So now we turn to our graphs. The first one is entitled “Increasing house prices a function of increasing loan sizes”.

The red line is the average home loan size and you can see loan sizes have risen steadily since 2002 but starting in 2019 they jumped dramatically. And at the same time the loan to income ratio on which banks were basing their loans skyrocketed from 4.5 to 6.5 times.

This massive infusion of money into the housing market spawned by lower lending standards is what has driven dwelling prices. Significantly there was a pause in the escalation around the time of the banking royal commission.

The second graph removes any doubt as to what has happened and is titled “45 per cent of the loan book is purely multiple expansion”.

The Evans & Partners chart shows in the blue space the level of bank home loans at three times income — the standard benchmark level. The red part of the graph represents loans that have been granted on income multiples above three — that’s where all the extra money has come from.

The banking regulator APRA did nothing to stop this and obviously took comfort from the Reserve Bank forecast that interest rates were unlikely rise significantly until 2024. Last month APRA became wary. It required the banks to assess new borrowers’ ability to meet their loan repayments at an interest rate that is at least 3 percentage points above the loan product. This compares to a buffer of 2.5 per cent that was commonly used.

Wilson says “it’s a very tepid gradual process” that is designed as “a shot across the bow” to the banks, saying “hey slow down”.

Our third Evans & Partners chart, titled “Australian Mortgage Repayments” shows what would actually happen in Australia if there was a sizeable increase in interest rates.

The red line plots the percentage of gross household income that is devoted to mortgage repayments and shows the current level is around 31-32 per cent mark — very close to the peaks of 2010 and 2018. But in those years interest rates were substantially higher.

With mortgage interest rates now at token levels we have not reduced the mortgage repayments share of household income. That means if interest rates rose by, say, 2 per cent or 3 per cent — which would still be low by past standards — it would skyrocket the percentage of household income required to service the mortgages beyond 35 per cent, which is a level that Wilson believes is not sustainable.

In the US, housing loan rates are fixed for long periods, sometimes up to 30 years, whereas in Australia, while part of the market has fixed rates for two to three years, the biggest segment is based on short-term interest rates. That means we are far more sensitive to interest rate rises than the US.

What makes the current situation so dangerous is that while shortages of goods can be overcome, after a decade of only small wage rises big parts of the workforce is now seeking to catch up. The high level of mortgage payments to income is part of that thrust. But if the higher wage thrust becomes widespread then it locks in an inflationary/higher interest rate cycle

I pointed out last week under the heading “Chronic supply shortages and inflation ahead” we are experiencing an economic a boom that we have not seen for many decades. The Reserve Bank is hopeful that somehow or other inflation will stay down around the 3 per cent mark. But the Australian bond market is having none of it.

Last August the 10-year bond rate was around 1.2 per cent. It is now rising strongly above 1.8 per cent.

The world benchmark rate — the US 10-year bond rate — jumped to almost 1.7 per cent earlier this month. Alarmed, the Federal Reserve stepped up its bond buying and pushed the rate down below 1.6 per cent but it’s rising again.

The bond market is our early warning monitor.

As Australia heads into a period of serious shortages of goods and labour, new research material is showing that the vast majority of the house price rises in recent years have been as a result of lower lending standards by our banks.