Of the 30 biggest blockbuster initial public offerings, investors are down a little over $30m in total, with more flops than hits.

Returns from the next 30 stocks where the size of the ASX listing trails off pretty sharply (between $20m and $80m) don’t get much better, with investors down a collective $16m.

The negative returns come in a backdrop of what was one of the strongest markets of the past five years, with the broader S&P/ASX 200 benchmark up 13 per cent, rebounding from a negative year during a Covid-hit 2020.

Among the 99 companies that raised more than $10m, more than half, or 60, are sitting in negative territory.

So the test still stands that by the time retail investors buy in, it is often too late.

The losses during such a strong year for equity markets should be a wake-up call.

It shows vendors, mostly between private equity and investment banks, have shifted the dial back to greed. They have been pricing untested businesses at boomtime multiples and now it is all coming back to earth.

Losses are expected to get even more pronounced, with the ASX heading into a period of volatility as interest rates around the world start shifting higher.

The Brian Hartzer-chaired buy now, pay later Beforepay, which kicked off this year’s poor run of IPOs, has so far seen its shares down 44 per cent on its $3.41 raising price, ranking it one of the worst debuts on the ASX.

Shares in the payments business were sold into a deflating BNPL bubble, while there is caution around the business model of offering salary advances.

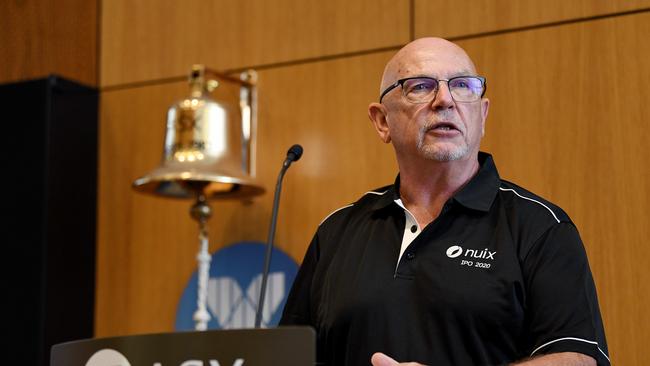

For its part, corporate regulator ASIC has been keeping a closer eye on the IPO market since the Nuix listing.

As well as accuracy in numbers, the regulator has been advising companies to include meaningful information around non-financial risks. This might be areas relating to how climate change could affect a company, supply chain risks or even the prospect the industry faces being “debanked” over time due to its carbon footprint.

The regulator is also understood to have stepped up scrutiny around the valuation of assets sitting on balance sheets.

Among the biggest IPOs last year, health services group APM Human Services shares are down 27 per cent in more than two months. Business bank Judo Capital is down 6.4 per cent, HealthCo REIT is off nearly 5 per cent. Others include Pepper Money, which is off 30 per cent, and bitcoin mining energy provider Iris Energy is off 66 per cent following its October debut.

However, it is not all bad news for investors. The $1.17bn listing of PEXA Group, which was spun out of Link Group, has gained traction and the shares are up 7.4 per cent. Elsewhere, the $627m debut of SiteMinder in October has delivered a 16.6 per cent return.

The standout case remains software provider Nuix, which made its market debut at the end of 2020, and has seen an implosion in investor returns following multiple profit downgrades, missed forecasts and an ASIC investigation into alleged insider trading that has cast a shadow over new listings. Nuix shares are now trading at a fraction of their $5.31 IPO price.

More than a year on, Nuix remains a reputational headache for investment bank Macquarie Group, which had a 70 per cent stake in the company and steered it to a listing despite governance issues bubbling to the surface.

Macquarie chief Shemara Wikramanayake has previously defended the bank’s role in the float, saying it had reviewed its IPO processes and found “no reason to believe” the forecasts could not have been achieved. Even so, Macquarie used the strength of its brand to help market the float.

Last year was one of the busiest for the IPO market on the ASX. It saw 99 listings of companies, with more than $10m in capital raised. JPMorgan noted this was the most in more than a decade and well up on the previous high of 55 in 2015. There’s a clear pattern of investor underperformance.

According to JPMorgan numbers, while the weighted average day-one relative performance of IPOs last year was strong at 7 per cent, returns faded over time with three-months relative performance only at 1 per cent.

Notably, the strongest returns among IPOs during 2020 also faded over time, with 12-month relative performance coming down 16 per cent.

Going back into the IPO class of 2020, a string of companies hit record lows this week, including Nuix (down 74 per cent), Booktopia (down 52 per cent) and Adore Beauty (down 55 per cent).

What are the lessons for investors? First up, fund managers say read the prospectus and understand what a company does.

At the most basic, investors need to know how a prospective company generates revenue. Also, ask about its so-called moat – its ability to maintain a competitive advantage and grow in its market.

What is its track record on earnings and what is the forecast? Just because a business is loss-making is not a bad thing, but what is the direction of the growth?

Most start-ups, such as Afterpay, lose money in the early years to fund the investment needed in the business. But watch the cashflows, which include borrowings, because all businesses are hungry for cash. Also, investors should look at how the shares stack up against other listed companies.

Other signs to watch for are what the business is raising money for. Marketing costs are usually a big red flag. Of the $35m recently raised by Beforepay, nearly half was earmarked for marketing and customer acquisition costs.

Also ask who is selling shares into the IPO and will the owners retain a stake and have skin in the game for the foreseeable future.

It’s not only investors who lose out on a float flop. For the companies involved, very often there is sound business behind an IPO.

One chief executive whose company remains under water conceded that a poor listing was like “always starting from behind”. Conversations with big investors become harder with greater demand on short-term performance.

johnstone@theaustralian.com.au

More people lost money on new stockmarket listings last year than made money. And that was in a boom year.