The state Crimes Act was supposed to impose criminal penalties for inciting violence based on race or religion and had been exposed as weak.

It was not used against any of those who had been caught in Sydney’s mosques targeting Jews for destruction.

The premier could draw little comfort from the fact that the equivalent law in the Commonwealth Criminal Code was just as useless.

This was a Sydney problem.

The wave of anti-Semitism started outside the Opera House and reached its zenith in a handful of the city’s mosques and universities where it was captured on video and disseminated globally.

The challenge for Minns was urgent. He needed to find a way of ditching Sydney’s current reputation as a safe space for anti-Semites and a dangerous place for Jews.

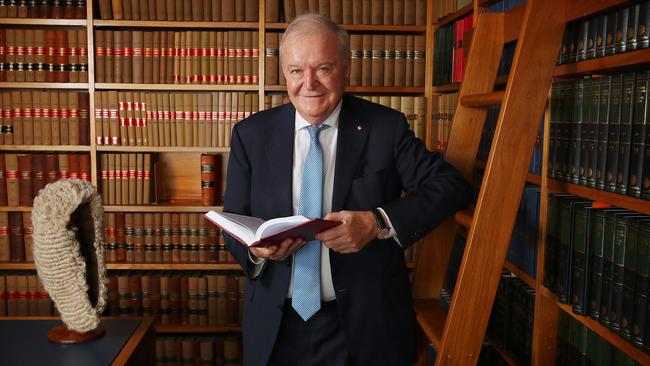

On February 14 he turned to former state Chief Justice Tom Bathurst and the NSW Law Reform Commission asking them to “expeditiously review” section 93Z of the Crimes Act – the provision that was supposed to deal with incitement of racial and religious violence.

Inciting violence is the main game. It is far more serious than the civil offence of racial or religious vilification which covers the lower end of the spectrum of hate speech.

By it seems that is how Bathurst and the Law Reform Commission have come to understand this problem.

They have just produced a paper outlining options for reform that might help excise the sickness that is afflicting Sydney without going over the top.

There are lessons here for the federal government.

This options paper is not the commission’s final position and it still needs to consider community feedback which can be made until June 28. So it needs to be treated with caution.

It contains ideas that could make it possible to crack down on those endorsing violence against Jews without taking the extreme step of criminalising speech that merely causes offence to particular religions.

Bathurst might just have headed off the rise of crude measures such as criminalising religious-based vilification and hate speech.

The options paper makes the point that opinions can differ about whether particular statements amount to religious hate speech – which is why it says this concept is not suitable for criminal law.

The real objective of this exercise, after all, is to crack down on incitement of religious-based violence – not to return to the Middle Ages with some sort of state-backed blasphemy law to punish critiques of religions.

The commission seems to be heading towards a principled position where hate preachers would suffer criminal penalties not because they cause offence but because they incite violence.

The options paper and some of the submissions leave the impression that Section 93Z suffers from two broad problems: the first is the way the law was designed; and the second is the overly cautious way in which it has been applied.

This provision was drawn up to deal with what is best described as direct incitement – clear-cut cases in which someone intentionally or recklessly threatens or incites violence towards others based on race, religion or several other characteristics.

But anyone with access to YouTube will see that the language used by hate preachers is generally not direct incitement but a form of words that is more accurately described as indirect incitement.

While this might fall outside the scope of 93Z the result is the same: violence against Jews is being championed.

The commission has received 42 submissions about section 93Z and the options paper notes that concerns were expressed that some of the language being used is “subtle enough to trigger violence but evade prosecution”.

“There were suggestions that ‘incite’ should be replaced or supplemented with additional terms as alternatives. Other terms suggested during consultations included ‘promote’, ‘advocate’, ‘glorify’, ‘stir up’ and ‘urge’,” it says.

One of the most compelling arguments for a broader approach to 93Z was put by the NSW Jewish Board of Deputies which drew on a 2014 report by a senate committee dealing with anti-terror legislation.

“It is no longer the case that explicit statements (which would provide evidence to meet the threshold of intention) are required to inspire others to take potentially devastating action in Australia or overseas,” the report of the senate committee said.

“The cumulative effect of more generalised statements when made by a person in a position of influence and authority can still have the impact of directly encouraging others to go overseas and fight or commit terrorist acts domestically,” it said.

Last Friday, in a case involving Indian man Avon Kanwal and the Sikh Kalistan independence movement, we learned that section 93Z is capable of securing convictions for clear-cut incidents of direct incitement.

Logically, therefore, don’t be surprised if the final report of Bathurst’s inquiry builds on that decision by expanding the scope of section 93Z to cover exactly the sort of indirect incitement that is being used against Jews.

Nor should anyone be surprised if the final report decides against criminalising speech that merely offends, insults, humiliates or intimidates – the awful formula that leads to civil penalties under section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act.

This seems to have been included in the options paper so it could be publicly rejected as inappropriate, just as the commission seems unconvinced about the case for a new offence of inciting racial or religious hatred.

Chris Merritt is vice-president of the Rule of Law Institute of Australia

Back in February, when it became obvious that Sydney’s hate preachers could spew their bile with impunity, NSW Premier Chris Minns knew he needed help.