This says much more about the current government’s approach to human rights than the recent hoopla about how a national charter of rights would solve our problems.

Here’s a reminder of the human rights mechanism that was bestowed on this country by Labor under Hawke.

Evans promised in an international treaty that every Australian would have the right to a remedy for breaches of human rights found to be substantiated by an international tribunal.

By acceding to that treaty, Evans also promised that a remedy for those breaches would be provided within 180 days and the federal government would ensure that nobody else would be permitted to suffer the same breach of their human rights.

Against this background it might at first seem difficult to understand how the Albanese government could choose to sit on its hands when confronted with clear breaches of human rights that have been uncovered by Geoffrey Robertson, KC, one of the world’s leading human rights lawyers.

But the pieces begin to fall into place once it is realised that the promises made by Evans might require the Albanese government to lead a reform drive among the trouble-prone network of anti-corruption commissions.

That might be the only way of ensuring the human rights breaches that were inflicted on Robertson’s client are never repeated.

On June 7 last year Robertson won a ruling from the UN Human Rights Committee saying his client, businessman Charif Kazal, had his human rights breached by the NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption and should be provided with a remedy within 180 days.

Kazal was declared corrupt by ICAC in 2011 but when independent prosecutors examined the material that formed the basis for this assertion they declined to prosecute him for anything.

There is no merits appeal available against ICAC’s findings.

A warning that something was wrong came from former District Court judge John Nicholson in 2017. When he was ICAC’s acting inspector he examined Kazal’s plight and said parts of the ICAC system might be in breach of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

On Tuesday, solicitors representing Kazal wrote to the Attorney-General’s Department pointing out that 180 days had elapsed since the Human Rights Committee ruled in his favour but no proposal had been made by the government for compensation and reparation.

“In the absence of a proposal being submitted to Mr Kazal, we hold instructions to instruct a forensic accounting firm to finalise its report concerning the quantum of a claim for compensation,” the letter from Mitry Lawyers says.

The point to keep in mind is that the mechanism put in place by Evans and Hawke provides a way of achieving a remedy for breaches of human rights – if the federal government chooses to honour the promises made on Australia’s behalf.

It is also worth keeping in mind that Evans and Hawke chose this route just a few years after Labor’s 1985 push for a charter of rights was abandoned.

Unlike a statutory charter or constitutional bill of rights, the mechanism under the First Optional Protocol has no implications for the role of the judiciary, nor does it subject this country to external supervision by some international court.

It is, in substance, nothing more than a promise to protect human rights, to provide a remedy for breaches and to recognise that the UN Human Rights Committee is competent to identify any breaches.

Soon after this initiative was put in place, Hillary Charlesworth made the point that while Australians could now take human rights complaints to the UN committee, this was not a judicial procedure.

“The committee’s adoption of views in a particular case are not strictly binding on the country concerned: the committee’s views are simply forwarded to both the state and the individual involved and are published in its annual report to the General Assembly of the United Nations,” she wrote in the Melbourne University Law Review.

“Publicity is thus the committee’s greatest enforcement power,” Charlesworth wrote.

This seems to have escaped the Albanese government. While it is free to ignore the human rights abuse inflicted on Kazal, to do so will damage this country’s standing on human rights and play into the hands of our adversaries.

It might also raise doubts about why Labor is pursuing a national charter of rights while refusing to abide by an existing mechanism to protect human rights that was put in place by Evans and Hawke.

Given what is at stake it is hard to avoid the conclusion that the government might have been choosing to ignore Kazal, Robertson and the UN committee because they have opened the door on a massive reform project for the flawed national network of anti-corruption commissions.

Fundamental rights such as privacy, the right to a fair trial, the presumption of innocence and the right to a reputation have been swept away by these non-judicial commissions.

The UN committee’s ruling of last year suggests that a remedy for Kazal might need to extend a lot further.

It says that under the article 2 of the ICCPR “the state party [Australia] is also under an obligation to take all steps necessary to prevent similar violations from occurring in future”.

This could be a case in which the abuse of one man’s human rights is being ignored in order to protect institutions that abuse human rights.

Chris Merritt is vice-president of the Rule of Law Institute of Australia

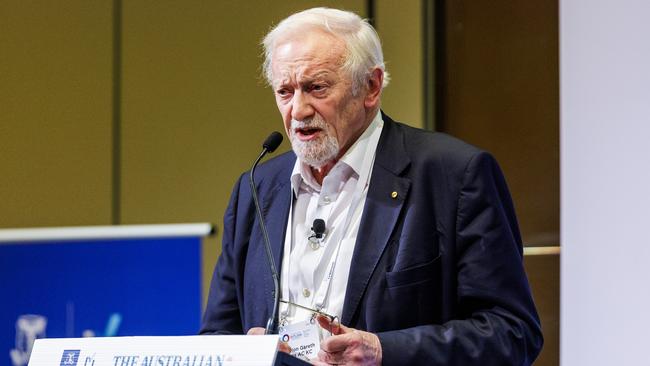

On September 25, 1991, when Gareth Evans was foreign minister, Bob Hawke’s Labor government made a series of promises on protecting human rights that the Albanese government seems determined to ignore.