More in store for Macquarie under Nicholas Moore

For Macquarie CEO Nicholas Moore, February 6 marks the 10-year milestone since he was named to replace Allan Moss.

For Macquarie Group chief executive Nicholas Moore, February 6 marks the 10-year milestone since he was named to replace Allan Moss. Moore took charge of the investment bank a few months later — just as the full force of the global financial crisis was about to hit.

It’s been a long time coming but the investment bank is a radically different beast from where it was before the crisis. Today about 80 per cent of its earnings are classed as annuity-style income, the smooth and predictable income stream through asset management, which oversees vast swaths of infrastructure on behalf of pension funds around the world or its leasing businesses.

The balance of its earnings comes from investment banking such as M&A advisory, equity capital markets activity and debt trading — something that it still dominates in Australia. As Macquarie shares push further past $100 each (closing yesterday at $101.98), this dynamic has become important. Investors reward companies with predictable earnings streams with higher share prices just as they mark down volatile earnings.

Ten years ago, as the financial crisis was gathering force, Macquarie’s earnings ratio was completely reversed with 30 per cent linked to annuity-style income and 70 per cent to capital markets.

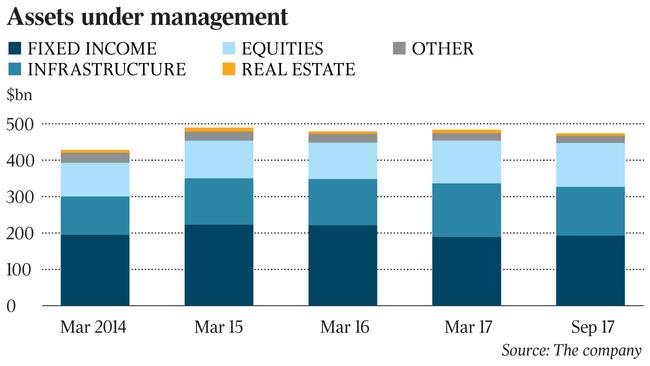

However, the extraordinary growth in the $470 billion Macquarie Asset Management arm — which is headed by the low-profile Shemara Wikramanayake, widely tipped as leading an internal field as Moore’s successor — could be in for a tougher run as the era of cheap money globally comes to an end.

The trillions of dollars pumped into quantitative easing programs around the world have pushed up asset prices, something that also benefited Macquarie significantly as it sells infrastructure assets from its funds acquired on the cheap over years.

Brokerage Citigroup recently noted as much, cautioning that Macquarie’s revenue is becoming lumpy again, growing at a faster rate than stable revenues, albeit from a much lower base.

Even so, few businesses listed on the ASX — and almost no other financial services player — can actually claim the composition of their earnings has been reshaped to the extent of Macquarie Group. That’s also in terms of growth in offshore earnings, with two-thirds now generated outside Australia.

It’s why the investment bank was truly stunned that it was classed as a “big five” bank when Scott Morrison slapped the banking tax on the big players in the May budget. Indeed, the next day, Macquarie, which has a reputation for employing some of the smartest people in the land, had never been so lost for words.

Macquarie issued a short statement saying it was “unclear” and “uncertain” about what impact the tax would have. For those looking for scale in banking, they won’t find it at Macquarie. Its lending and deposit books are smaller than Bendigo Bank’s and only slightly bigger than Suncorp’s.

Macquarie is still a player in infrastructure but its focus has shifted from toll roads and airports to something with a greener tinge.

It sees a massive amount of funds being invested in the renewables space over the medium term and wants a piece of the action. Today it is one of the biggest global private investors in green energy, with more than $15bn invested or arranged in renewables since 2010. This includes recently leading a consortium to acquire Britain’s Green Bank for $4bn — something that it plans to use to expand into mainland Europe.

For Macquarie, the master of reinvention, the trick is to find where it sees the next opportunity. In John Durie’s annual chief executive survey, published in The Australian shortly before Christmas, Moore nominated three main areas of growth for the bank: renewable energy, infrastructure and city building, and technology.

Renewable energy, he said, “extends into many areas of our business” and the bank has been active in the area for 10 years. Moore noted that Macquarie is already actively participating in building and connecting the cities of the future. Meanwhile technology and innovation is where Macquarie is looking to make inroads into retail banking.

For a read into the timing of Moore’s inevitable retirement, Macquarie is giving little away. But it can be said that much of his agenda has been implemented, including a re-engineering of the bank to take it away from the higher risk, pre-financial-crisis vehicle it once was.

For history buffs, it is worth noting that at the time of Moore’s elevation he was overseeing Macquarie Capital, an investment banking business at its core and responsible for 50 per cent of group-wide profits. In the last set of results, Wikramanayake’s asset management business accounted for 45 per cent of Macquarie’s profit contribution.

Still, recent top-level changes have provided an excuse for Macquarie to hold back on activating its succession plan.

The retirement of Stephen Allen as chief risk officer created a top-level reshuffle, with chief financial officer Patrick Upfold moved into the all-important chief risk officer role and Macquarie Capital’s Alex Harvey replacing Upfold.

At the same time, keep an eye on the progress of a $1bn share buyback program. Announced in October, Macquarie is yet to push the button on this while it considers whether the funds could be used to back another buying spree before the cycle well and truly turns.

The author holds a position in Macquarie Group shares.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout