From Moscow with a mission: Lessons from a history for Netwealth

The unusual resume of Michael Heine proves he’s no ordinary boss.

Bartering commodities behind the Iron Curtain at the height of the Cold War and walking miles around a frozen Moscow to avoid being listened to by Soviet spies. Trading hundreds of millions of dollars of steel for BHP in Japan, South America and Europe.

Pioneering mortgage funds and property trusts, making a fortune in Melbourne commercial property and losing the rights to one of the biggest buildings on Collins Street in a bitter shareholder battle.

Top-rating radio stations bought for $90m with only a $1m deposit and then sold for $130m days later, only to later lose the entire profit. And then, finally and more recently, overseeing one of the most successful ASX floats in recent years.

It is an unusual resume for the managing director of a listed company, but Michael Heine is no ordinary boss.

Heine has spent a lifetime building businesses, yet at the age of 70, he and his son, Matt, are at the helm of their best venture yet as joint managing directors of the listed wealth management platform Netwealth.

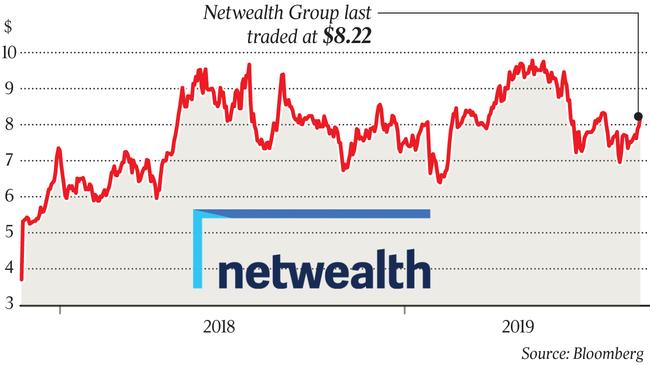

So successful has Netwealth been in less than two years on the ASX, during which the company’s shares have doubled in value and this week entered the ASX 200, that Heine has been catapulted to the elite ranks of the nation’s billionaires. On this year’s edition of The List — Australia’s Richest 250, published by The Australian, Heine and his family rank 66th with wealth of $1.3bn.

Yet Netwealth, the Heines joke, is a 20-year overnight success story, having been formed in 1999 after Heine had sold out of fund manager Heine Management in a $112m deal with Mercantile Mutual.

Netwealth is making a big investment in its operations to take advantage of the flight from the big banks by wealth advisers in the wake of the royal commission, with Heine saying: “We don’t want to be sitting here in three or four years’ time saying if only we’d done something. We want to sit there and say ‘thank god we did invest at the time’.”

Netwealth is not aligned with banks or other financial services groups, something that has helped it grow its business as the banking royal commission has kept competitors in the headlines for negative reasons.

But it has not always been an easy ride, as Heine has recorded for decades in the family’s “Lessons from History” — a document passed down between generations that records the lessons learnt during the highs and lows of business, through credit crunches and high interest rate eras, recessions and downturns.

“It gets expanded from time to time and it has some good things in there [including] basic and simple things like having a business plan and knowing where you want to go,” Heine says. “Another lesson is it ultimately is your fault. It is ultimately your responsibility. Taking responsibility for when things go wrong is more important than taking responsibility for when things go right.

“And for families or family-owned businesses, it is very often they continue to focus on ‘dad always did this or this is grandfather’s business’ [but] the world is changing around them and they are not prepared to adapt. Just because dad did zip 100 years ago doesn’t mean we have to do it today or do it that way.”

Business snatched

Heine is talking from his family’s rich — often extraordinary — history business. His father Walter, a German of Jewish heritage, ran a successful textiles business from Leipzig that was ultimately snatched from him by the Nazi government.

While Walter Heine was in London on business he was mistakenly identified as an enemy alien rather than a war refugee and was deported aboard the ship Dunera to Australia. The vessel had capacity for about 1600 people but about 2000 Jewish refugees, Italian fascists and German Nazis were crammed aboard in wretched conditions.

Walter Heine would eventually end up in an internment camp in the NSW town of Hay, via Tatura in Victoria, and later released to serve in the Australian Army, albeit in non-sensitive roles.

After World War II ended he would establish a trading company, Heine Brothers, which traded in products such as steel, wheat, wool and coal around the world, bartering with governments and companies. It would trade hundreds of millions of dollars of steel for BHP, import instant coffee and trade dozens of other products.

“The Chinese would skim their lakes for the water fleas and we sold hundreds of tonnes to Europe of that,” Heine says. “You might wonder what you do with water fleas. Well, it’s dried out and used as fish food.

“Dad started the business of sending wool, wheat and steel to China. All that exists today is founded from that. Not iron ore, though Dad did peg an iron ore lease in [Scott River] Western Australia and got an act of WA parliament for the first export licence. But as soon as Dad got that through, a bloke called Lang Hancock said ‘look what I’ve got here’.” Heine jokes he joined the business aged one — “that was what we talked about, it was Dad’s only hobby” — and says he travelled the world so extensively he can’t remember how many countries he’s visited in his life.

“We would go to trade fairs in Leipzig. We knew an intermediary with the [East German] government there and with one call we’d be waved through Checkpoint Charlie [in Berlin]. This is what socialism was really about!”

Then there were visits to Moscow, then the communist capital of the old Soviet Union. Heine recounts meetings with the then Australian ambassador, who would insist they trudge several miles in -40C temperatures in order to discuss business without someone listening.

Heine Brothers also employed a former trade commissioner in the late Laurie Matheson to run their Moscow office, with Matheson later going on to be thought to be an operative of ASIO — and perhaps even Soviet intelligence forces — and be central to the 1983 Combe-Ivanov affair that saw the Soviet first secretary expelled from Canberra.

“They were the exciting spy days. I remember Laurie would constantly tap on the table while we were talking. It was very annoying, but he did it because it was true spies, espionage and counter espionage times … and they were listening.”

As technology improved and financial markets grew more sophisticated, the need for trading houses would diminish. Heine admits the family probably did not see harder times looming — another of his lessons is to try to constantly anticipate the future — but crucially the business had by the 1980s started doing some mortgage lending using cash flows generated by the trading business.

That led to a move into unlisted property and mortgage trusts and even a battle for Melbourne’s 120 Collins Street that Heine Management bought from Kerry Packer and the Grollo family. That would later end in acrimony as BT seized control of the Grosvenor Trust Heine had listed to own the property. “For a long time, wherever I went, I looked out the window and thought ‘damn there’s that building’.”

Venturing into media

The 1980s also threw up other opportunities, including radio stations with Heine’s friend Glenn Wheatley. One big deal was putting down a $1m deposit to buy the MMM radio stations for $90m, only to flick the business on days later for $130m to Hoyts Media.

But the $40m profit was squandered as Heine took shares in the new company, which would collapse when the advertising market turned downwards.

In 1999, Heine Management was sold to Mercantile Mutual and Heine was searching for what to do next. With his interest in financial services and advising and technology, Netwealth was born, with a handful of staff and a business plan to build an online platform for financial advisers to manage their clients’ investments on offering dozens of products with state-of-the-art technology.

“The original plan was in three years we expected to have 100 advisers and $30m on the platform, $3bn [funds under management and advice] and we’d be quite profitable.”

Yet Matt Heine says it took a good five to six years for Netwealth to break even, when it reached $1.2bn funds FUMA.

“We were doing everything from writing privacy policies to seeing clients, designing websites and advertising,” Matt Heine says. “The typical response was you’ve got no clients and no money under management.

“We would have a non-super product and someone would say, well you need a super product. Then it was insurance, and then something else. So we spent a solid seven years playing catch-up. But we started to lead the market in a few things and then off we went.”

The senior Heine, meanwhile, says by about 2015 he realised the business was of sufficient scale to be a considerable success. More lessons followed, including a preference for recurring revenue — Netwealth earns fees from the users of its platform — risking their own money rather than someone else’s and an absolute belief in making a profit. No growth for growth’s sake.

By the time Netwealth listed on the ASX in November 2017, the firm had $17.4bn FUMA. Then came the banking royal commission, and a paradigm shift in wealth management away from the big institutions.

“There’s a lot of trust that has been lost across many industries, and that has got to be rebuilt, but from our point of view we are in a really good position to capture the market because the trust has been placed in us and is not being questioned,” says Michael Heine.

Today, the firm is aiming for a whopping $30bn FUMA by the end of June next year and is investing in its technology and systems to capture more wealthy individuals and families and quickly build the wealth managers already on its platform.

There is time for a couple more mantras from Heine’s “Lessons from History”: Stay in control and be prepared to make mistakes, but not big ones that could destroy a company.

“When you see the losses mounting, you say are you doing the right thing. This is the difference with an entrepreneur to anyone else: he believes his own bullshit,” Heine says.

“I also like to have more shares than any of the other bastards put together. It makes decision-making easier, but it goes back to also if I get it wrong, I know whose fault it is.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout