How Paul Howes tamed his dogmatic demons at KPMG

It was in a Harvard lecture theatre that Paul Howes suddenly saw in himself the primitive instinct that was stalling his career.

The nondescript national headquarters of the Australian Workers Union at Granville in Western Sydney is a world away from the perfectly manicured lawns and grand 18th century buildings of the Harvard Business School in Boston.

Yet one morning in the northern summer of 2015, Paul Howes — for 15 years a poster child of the union movement after a seven-year stint as the youngest-ever leader of the AWU — ironically found himself sitting in a lecture theatre of Harvard’s aptly named Organisational Behaviour Department.

He’d been sent on an all-expenses-paid, two-week management course aptly titled “Leading Professional Services Firms” by his still relatively new employer, accounting giant KPMG, which he joined in 2014 only a month after quitting the AWU.

As Howes listened intently to famed lecturer and author Thomas J. DeLong speak about one of his top performing students, an investment banker from the wrong side of town, it suddenly hit him.

“He talked about the inability of this guy to make the next level of leadership because of a behavioural impasse,’’ Howes tells The Weekend Australian in his first interview reflecting on his six-year transformation from headline-making union hitman to suit-wearing, BMW-driving accounting partner.

“I remember leaving the lecture and ringing my wife and saying ‘It was like this guy has looked into my soul and found who I am and why I am struggling to get to this next level of leadership in the firm’.”

Over a decade and a half in the union movement, if Howes had a bad interaction with someone, his response had been simple. And primitive.

“I would have immediately afterwards thought, as they do in politics, how do I get that person?” he now recalls.

“For me it was the most surprising element of selling out and moving to the other side. The personal development here at KPMG is far more significant than in my former life, where the feedback was ‘You are a dickhead and if you are one of mine, keep being a dickhead, and if you aren’t, I’ll get you’.”

Howes admits he brought to the accounting world a “Bonaparte” style of leadership, which irked many.

One feedback session with the firm’s HR tsar Deborah Yates was telling. She told him his behaviour not only limited his ability to be successful in his current role, but completely wiped out any opportunity for him to move up the ranks.

Howes was creating a culture where people actively avoided telling him bad news. For a time his reputation also worried the man that hired him, KPMG chief executive Gary Wingrove.

“If he didn’t agree with something or somebody had done something he didn’t agree with, he would be vocal on that. When he joined us originally, there were some inside the organisation who asked ‘Did we get this right?’,’’ Wingrove recalls.

But the transformation of the now 38-year old Howes has impacted not only the staff at KPMG, but the lives of his children from his first marriage and his wife of the past six years, Qantas loyalty boss Olivia Wirth.

These days Howes carries a black notepad in his suit pocket. In it is scrawled his personality profile and he looks at it every day and speaks to his fellow partners about it regularly.

When he has a bad interaction with a colleague or client, he immediately starts thinking to himself: “What do I do to rectify that? How should I have done that differently?”

“I was never before conscious of the impact I could have on others with my personality and my dogmatism as it existed sometimes. It is really confronting to get that feedback initially. I found it really, really hard,’’ he says.

“A lot of people thought I would be OK with that sort of feedback because I had been criticised so roundly in my former life. But it is very different being a called a communist to someone saying ‘Actually, you really have a negative impact on people because of these three things that you do’. I still to this day really struggle with adverse feedback. You feel it in your guts. I still feel like it’s a personal blow.”

Gary Wingrove says Howes has quickly learnt that there are times in professional services when you need to come to a consensus. Where two or three brains are better than one.

“He is still a strong decision-maker but he has learnt you get a better outcome from consensus.

“If you asked people on our executive team, they would comment on that as well,’’ he says.

Lower profile

It was former Business Council of Australia chief executive Katie Lahey and former Morgan Stanley Australia boss-turned Westpac director Steve Harker (a former research officer at the Federated Ironworker’s Association) who advised Howes during his final months in the union movement to lower his public profile.

Lahey specifically told him that if he wanted to have a proper business career, he needed to take a step back to prove himself, not just be a “walking headline”.

He also took advice from his psychologist, who told him to get out of the AWU for the sake of his sanity.

Howes has previously revealed that one of the reasons he left the union movement and the world of politics was the crippling impact it was having on his mental health.

For the past six years he has been a board member of Beyond Blue, the mental health-focused not-for-profit chaired by former prime minister Julia Gillard.

“I had crippling anxiety at the time. I didn’t talk to anyone about it,’’ Howes says.

“That was not something I ever had the courage to talk about when I was in the labour movement because that would have led to it being a point of attack.”

He says the final straw came one Saturday morning in the Westfield centre at Bondi Junction in Sydney when he was shopping with his son, Sam.

“Some crazy guy came up and started screaming at me about the carbon tax. Sam turned to me and said ‘Dad, why do they hate you so much?’

“I always think people who relish being famous have some deep issues that need to be resolved because there ain’t many upsides to it. Being recognised isn’t much fun,’’ he says.

“I wanted a different career and I didn’t want my previous career to define my next career. So I thought to do that effectively, I would have to take a deliberate step back.”

It took two years for Howes and Wirth to consciously kill their public profiles. Wirth earned hers as the Qantas PR spinner who stared down the unions alongside her boss — and Howes’ good friend — Alan Joyce in the infamous 2011 grounding of the airline.

For many months after starting at KPMG Howes was regularly named in newspaper coverage of the royal commission into the trade union movement.

Yet he forced himself not to return phone calls, not to bite when provoked. He turned to friends in politics for advice, who counselled him to treat his profile like a drug addition.

“I was very conscious at becoming truly faceless,’’ he quips with a smile, referring to his infamous tag as one of the “faceless men” who helped remove Kevin Rudd and install Julia Gillard as prime minister.

His initial role at KPMG was to build the firm’s customer, brand and marketing advisory offering and he felt the weight of expectation from the start.

For a time he felt like an impostor, sharing offices with partners boasting triple degrees and doing multi-billion-dollar deals. Howes didn’t even have his year 10 leaving certificate from Blaxland High School in the Blue Mountains. Just the gift of the gab.

“I thought there was a high chance of failure here. I thought I would fail everyday. I felt that pressure from the media and others outside the firm. But I never felt that pressure inside here. They wrapped you in support. I was fortunate the firm took a punt on me. That is why it is a great place to come as a lateral. I love that we hire really diverse people because we have such a great way to help you change,’’ he says.

“Everyone is personally invested in your success. When you are a partner, no one benefits from another partner failing. That is a genuine cultural construct within the firm.”

Gary Wingrove remembers Howes being the subject of several controversial newspaper headlines early in his tenure.

“I remember getting a few phone calls from him on a Monday morning where he would say “Are you going to fire me?”

On one occasion Howes was so convinced he would be axed he made a phone call on the way to work to the then Sky News boss Angelos Frangopoulos, who had earlier that week offered him a commentary slot on the network.

But Wingrove had his back.

“I remember I told him ‘Relax, you are not going to avoid these things, you have a brand. But focus on your role here and your brand will change. We will back you and support you.’ ” Wingrove recalls.

Howes says he is a completely different person now because of the coaching, feedback and the processes that he has been through at KPMG, including the stint at Harvard.

“People talk about this being a boring accounting firm,” he says.

“I just think it is such a special firm and we are so fortunate to be a part of it and we need to remind ourselves constantly of how lucky we are to be here. I have never felt more supported in my career than here.”

COVID challenge

In July 2019 Howes was appointed national managing partner of the KPMG middle market, enterprise business and a member of its 12-person national leadership team.

His staff are spread across 16 offices and their work ranges from assisting a small business to access finance for an expansion, to running managed services in finance hubs for some of the world’s biggest corporations.

Howes notes it is the most “pure-accounting component of the accounting firm” but that the middle market is “the biggest untapped market for KPMG and our competitors”.

“That is the engine room of the Australian economy. For us to continue to thrive, we will need to have more dominance of that sector,’’ he says.

That will mean changes to the way KPMG delivers middle-market services, especially evolving its existing services and capability from large clients to smaller players.

Going into the COVID-19 pandemic the enterprise business had one of its best years in the past decade and Howes says it has not been hit as hard by the pandemic as he expected.

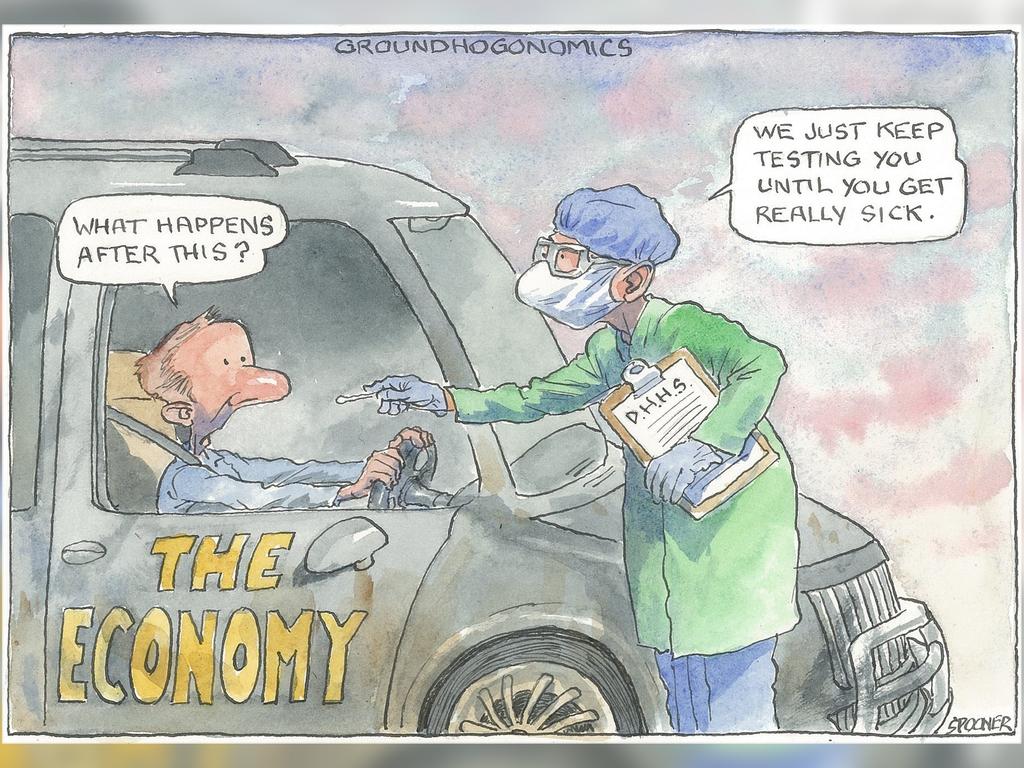

But the true test will come when the federal government’s JobKeeper support package is withdrawn in September.

“We are still yet to see the full economic impact on the mid market. The 2021 financial year, particularly the first and second quarters, will be tougher. We do have large sections of the economy on a drip from the government which will inevitably be eased off. In sectors like tourism, hospitality and retail, it takes two quarters for the full impact of that to be washed through,’’ he says.

Howes believes the long-term impacts of COVID on the accounting profession will be substantial.

In April KPMG cut 200 staff and asked employees to temporarily take a 20 per cent cut in monthly salary (from May until August), and partners took an effective pay reduction of up to 36 per cent for the same period.

It agreed this week to repay some of those salary cuts, but Gary Wingrove was downbeat about the year ahead.

Deloitte this week also cut 700 staff after revenue collapsed in May and June, while PwC has cut 400 roles in its consulting and financial advisory businesses and support functions as a result of the pandemic.

“The multi-jurisdictional delivery models for some of our engagements and work will change,’’ Howes says.

“The biggest impact for us is the impact on ways of working. I have sat in this office here at home on my own for 12 weeks. That was unthinkable beforehand. It is remarkable how well we have done to make that work. I think some of those changes will be permanent. I think the office will become even more agile — the office will not be the place you go every day; you will go there for a purpose and a reason. That will present lots of threats to our profession but it also has enormous opportunities. And I think for professional services there are more opportunities than there are threats.”

Ask Howes if he harbours ambitions to run the firm, and he returns momentarily to the political speak he honed so well in his union career.

“I have been on the firm’s executive for 12 months. That has been a real challenge and one I have enjoyed,’’ he says.

“Frankly I am not thinking about what is left after this. I want to complete this part of my journey first before I think about what is next.”

He is thankful for being thrown a new challenge every two years: first it was running the marketing practice, then financial services, now a mid-market practice.

“Paul is now one of four people of 11 on our executive team who have joined our organisation from the outside as direct entry partners or in Paul’s case, he became a partner quickly,” Wingrove says.

“He has done an outstanding job and shown his capacity to build a business. I have grown to genuinely like him as a person.”

But Wingrove defaults to his trademark straight-shooting style when asked about Howe’s chances of succeeding him.

“He is not in the short list for my succession, which is 12-15 months away,’’ he says bluntly.

“I think he has the leadership skills and business nous. He just needs a bit more time in the firm. But yes I think he has the capability to be the chief executive of KPMG one day.”

If Howes does get that honour he will be in a far better place mentally than the day he first walked into KPMG’s Sydney offices six years ago.

He says his son Sam, now doing year 12, and his two girls Zoe, 14, and Sibilla, 10, are “the biggest fans of my move from public life.”

“I don’t think I have any relationship that has not improved since leaving the unions,’’ he says.

Two and a half years ago he and Wirth purchased a cliff-top home in beachside Bronte in Sydney’s east boasting stunning views over the Pacific Ocean, a product of Wirth’s wish to revisit her beachside childhood growing up in Terrigal on the NSW Central Coast.

Howes says he is a “completely different person” because of his decision to abandon his roots and embrace the white-collar world.

“When I joined I didn’t think I would have a long-term career at KPMG. I had conversations with a couple of banks, manufacturing companies and consultancies. I thought it was a place I could wait for one to two years until I found my feet in the consulting world,’’ he says. “I now thank my lucky stars I didn’t end up at some of the other places I was talking to. What the firm is on the inside is radically different from what it looks like from the outside. I now would be happy to stay here from the rest of my working life.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout