‘He saw death every day’: How the Holocaust forged an auto family legacy

Tom Jacob remembers his Dad’s sweat-soaked clothes from hours of swinging a hammer in his Melbourne backyard business. Today he helms the $200m auto empire forged from that hard work.

Guenter Jacob worked like a man possessed.

Every evening his clothes were soaked with sweat from hours of swinging a hammer for the suspension parts manufacturer he started in his backyard in Melbourne suburbia in 1958. It was called Jacob Spring Works.

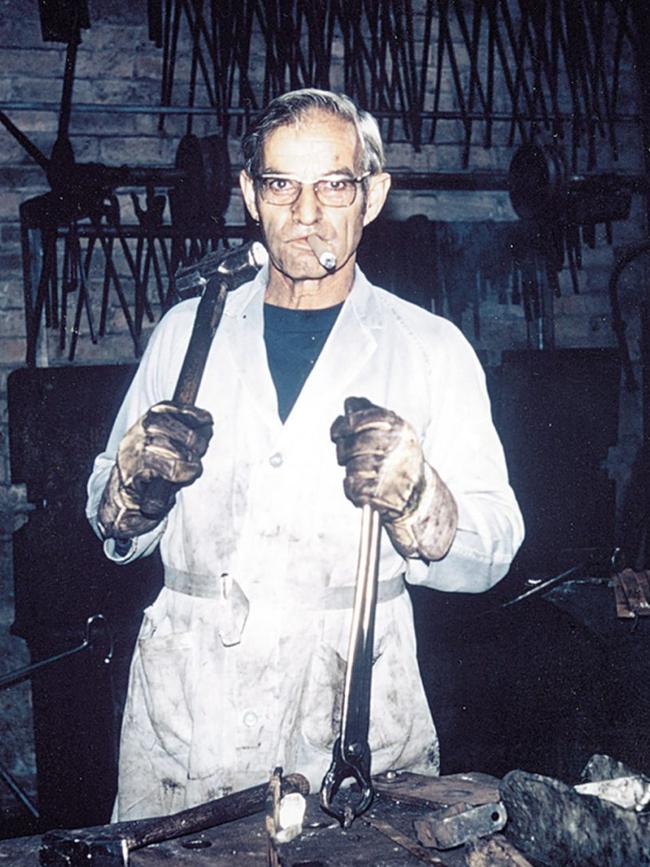

Jacob was known in business as the man with the cigar, given that he smoked at least 20 of them a day. His firm, later known as JSW Parts, became Melbourne’s largest producer of springs for trucks before he passed away in 1985 from a heart attack at the age of 67.

“When he died, his doctor said, ‘You know, I believe that human beings have a vital force, a survival force. When they are confronted by death experiences, and particularly what he went through in his life – regardless of the cigars – that is finite,” his son Tom now says.

Guenter had been running the family’s metal business in Germany in the 1930s when it was taken over by the Nazis and he and the rest of the family were shipped to the Auschwitz death camp. His metalworking skills saved his life but not those of his loved ones.

“When you experience something like what he saw, it is not fathomable. He used to say he saw death every day, from 1942 until 1945. You can’t think about what that means to a person,” Tom says, noting his father never shied away from speaking of the horrors he endured.

After the war ended, Guenter emigrated to Melbourne. Tom was born in 1955, five years after his sister Barbara.

“So I grew up in a house where there was always a storehouse of tinned food, big pots of flour and big pots of sugar for an emergency. Because my father was always prepared for the worst. He slept with an iron bar under his bed,” Tom recalls.

Tom was 30 when his father passed away, and instantly became managing director and half owner of the family business. Barbara inherited the other half.

Over the decades it has evolved to be manufacturer and supplier of suspension parts around the world, and today is known as Ironman4×4, providing accessories to meet all the demands of off-road users in 167 countries.

It is the second largest four-wheel-drive accessories company in Australia – an untold story of Australian ingenuity and hard work in a family business that now turns over $200m annually from its headquarters among the industrial sprawl of Dandenong South in Melbourne’s southeast.

But Tom will never forget the day he lost his dad and the emotions he felt in the months and years after.

“The things that people don’t understand about running a family business is how lonely it is. It is an extremely lonely experience. Solitary. You are surrounded by many but you are really on your own and you’ve got no one to fall back on but yourself,” he says.

“Some people can deal with this and achieve, some people can’t. In my case, I didn’t get a choice. We’d just travelled to Japan. I’d kissed him goodbye at Tullamarine Airport.

“He went home and died in his bed that night. It always struck me how lonely it was without him,” he says, before a painful pause. Then, for a moment, he breaks down in tears.

Tom’s eldest son, Samuel, who has joined for this interview and works in the family business as an executive director, hands his father a napkin to wipe his eyes. After composing himself, Tom continues.

“I had the legacy of stepping into the work that my father had started,” he whispers. His mother, Mimi, who he describes as a “rock” and a “lioness” for the family, died in 2003.

“I’ve had a very beautiful, wonderful life. Great parents, great childhood, great opportunities. I’ve never had to be tested like my father was and I don’t want to be. But there is no question that the experience of our family affects who we are.”

He turns to his son and, once again choking back tears, asks him a question: “What did you ask me in Germany once? We were sitting by a river. You were very emotional.”

Samuel looks me firmly in the eye and without flinching, replies to his father’s question: “I asked him that day, ‘How will I ever be able to fill your shoes Dad? Dad replied, ‘You don’t have to fill my shoes. You just have to fill your own’.”

Real Ironman

In 1988, JSW Parts launched the Ironman 4×4 brand of springs and suspension parts, and a decade later changed its name to match the brand moniker.

Tom Jacob, who is 68 this year, says the name was initially modelled on the quintessentially Australian beach ironman who excels at running on land and swimming at sea, and is adaptable to all conditions.

“But later on, I actually discovered what ironman really meant to me. It was really my father. He was our ironman,” he says proudly.

“He survived the hell of Nazi concentration camps to be born a second time, as he would say, in Australia. So he’s the real ironman.”

The suspension kit products Guenter Jacob designed decades ago are still being sold around the world today, and the family now donates 10 per cent of those sale proceeds to secular and Jewish charities.

In 2014 Tom Jacob was recognised with an OAM for his charitable contributions to the King David School, Mount Scopus Memorial College, and Yeshivah and Beth Rivkah Colleges and other general community institutions.

“I think we live in a time where we need to have heroes. My father is a hero because he survived and he built us into a family, which is now into its third generation in this business. That really matters to us,” he says.

For a time Tom Jacob turned his hand to journalism, working for The Age for six years after scoring a cadetship as a 17-year-old in 1972. But with his father’s health failing, he and his sister joined the family business.

Their big break came in 2005 when Ironman secured a contract to supply the US military with vehicle accessories for the war in Afghanistan.

Today the firm’s four-wheel-drive accessories are supplied to vehicles used by the United Nations, the World Food Program and the World Health Organisation, as well as the defence, mining and agricultural sectors.

As Tom Jacob puts it, Ironman’s mantra is simple: “Follow the vehicles and find the opportunity.”

Its secret sauce has always been engineering and its ability to design solutions for a global market.

The firm now has six distribution warehouses across Australia and has operations in Africa, the Middle East and Asia. It has 150 retail stores and is planning hundreds more.

On the board is businessman Steven Fisher, a former chairman of appliance maker Breville and current chairman of The Reject Shop.

“I had a call from my GM in Thailand to say that the emissary of the King of Bhutan wants us to prepare two vehicles for him. These people search out the brands or products that they want around the world and brand Australia means something,” Tom Jacob says passionately.

“Australian businesses can look to people who believe that Australia can punch above its weight across the world. We so often undersell the ingenuity and the capability that Australians have always had. I think we need to believe that dreams can become reality.”

US opportunity

Ironman’s next big growth opportunity is the American market, which it entered in 2020.

So far the business there is up to 90 per cent online. But five retail bricks-and-mortar stores have been established and hundreds more are planned.

“The business in America literally took off from day one because the internet had already exposed our products to the world,” Tom says.

“The Ironman brand was already well developed and people have always looked back to Australia for the way we used vehicles, particularly in overlanding. Australian brands do well in America because they are absolutely relevant.

The US expansion has been spearheaded by the now 29-year-old Samuel, Tom’s son to his second wife. Samuel planned to live in America in 2020 before the Covid-19 pandemic forced him back to Australia.

Tom says he had no expectation his son would enter the business, even though, deep down, Samuel dreamt of doing nothing else.

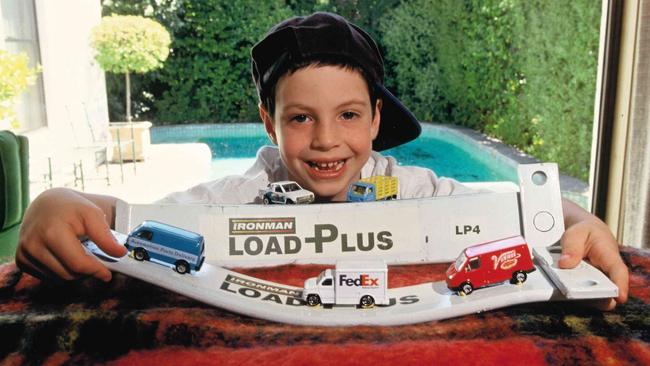

“As a young boy growing up, you just want to be like your dad. You want to follow him. I remember playing at his desk and sending off pretend faxes and talking on the phone back when we were in Moorabbin. I’ve had the most incredible role model and mentor to look up to in my dad,” Samuel says, recalling he was only seven when he sold his first 50 load-plus springs to Ballarat Toyota.

An image from that day hangs proudly on his father’s office wall.

“I came to the end of my plumbing apprenticeship and dad offered me the choice of whether I wanted to join. He had one condition which was if I did join the business, I needed to travel,” he says.

“I needed to learn a bit about the world, which I did. So, coming into the business, there was a lot for me to learn practically. But it always felt very natural. It always felt like a second home.”

Tom and his sister Barbara each have two children but Samuel is the only one in the business. Barbara’s son, Daniel, once was but is no longer.

Her daughter, Rebecca, is a cheesemaker and Tom’s daughter, Maggie, is a singer in Ireland.

Barbara is now retired but Tom quips that his big sister is still “in charge of me”.

“She is little and has an indomitable spirit. I think that is the spirit of my mother,” he says proudly.

The group has always reinvested its profits in growth and had no debt. Tom claims the firm has achieved a compound average growth rate of 20 per cent for the past 22 years, funded all internally.

But now he says the time has come to look for an external investor in America.

“We are very fortunate that we don’t need it for the capital. But what we really want and seek is a large group that already has a retail footprint,” he says, stressing a public float is not currently on the agenda.

He has no great wish to currently crystallise the family’s wealth. Rather he wants to continue to grow, honouring his father’s amazing legacy.

“We’ve still got a long way to go to build this business into a store footprint that could see us add 1000 stores across the world,” he says.

He also loves working, especially with his son by his side.

“We walk this journey together and are very close. I’m really happy continuing doing what we are doing and building this future together. There is no obligation to build a legacy.

“There is work to be done. Being a true entrepreneur is not just about being resilient, it is actually about having a vision and then finding and putting together the right team to be able to execute that vision.”

“My father would never, ever have dreamt of what we have achieved so far. I will probably never dream of what Samuel will one day achieve.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout