Laurence Escalante: From Christian games to $4.37bn VGW empire in Perth

Laurence Escalante could have stayed a Christian computer game maker and treasurer of his local church chapter. Failure led him instead to a $4bn online casino fortune and notoriety, but he swears he’s no sinner | WATCH

If things had gone according to plan, Laurence Escalante would have had a career developing Christian computer games based on the Apostle Paul’s disciples, Timothy and Titus.

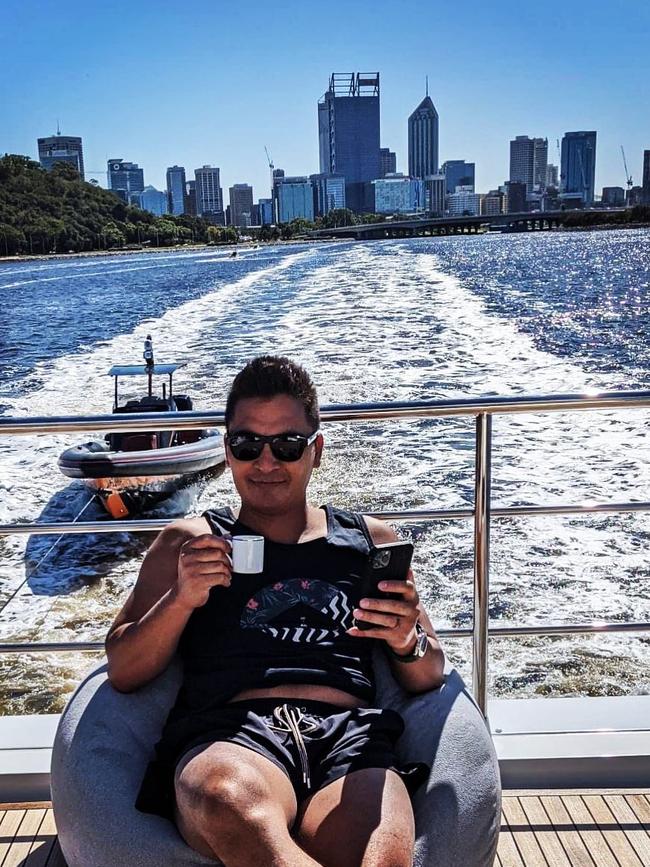

It may have been a decent earner, but it’s unlikely to have brought the level of success the 43-year-old has quickly attained in a decidedly less pious way and allowed him to live what is – judging from his social media accounts – quite the hedonistic lifestyle.

Escalante is the founder and majority owner of Virtual Gaming Worlds, which has quickly become one of Australia’s most successful homegrown technology companies, operating an online casino gaming business from Perth under a sweepstakes model that has most of its customers in the US.

Once a loss-making startup with a failed attempt at a backdoor ASX-listing, VGW only broke even in 2018 and is now one of Australia’s biggest private companies.

It had $6.1bn revenue last year and made a whopping $497m net profit – enough for Escalante to already have an estimated $4.37bn fortune, placing him 32nd on The Richest 250 List this year.

But if it weren’t for an American video games publisher striking financial trouble and leaving Escalante with a $250,000 debt and his family home mortgaged to the hilt in his late 20s, by Escalante’s telling, “none of this would have happened”.

There would be no $100m collection of sports cars and boats and a corporate jet, no partying in Paris and other glamorous locales, no front row seats at concerts, nor the nightclubs, huge sponsorship deals with Formula 1 racing giant Ferrari or anything else chronicled on his Instagram account. Neither would Escalante’s growing philanthropic efforts exist.

While admitting he isn’t as religious as he once was, Escalante insists he is no sinner. He reckons he doesn’t worry about his reputation, and says he is simply revelling in success earned from hard work and learning from previous business failures.

“I’m having fun, enjoying life,” he says in a rare interview. “Being in the moment. I’ve always been that sort of person, [wanting] to enjoy life.

“I was always into cars; I just didn’t have the means to enjoy them. Now I can afford a jet … You have to enjoy life. You never know when it could disappear.”

Christian video gamer

It has been reported that VGW is losing market share as copycats and competitors emerge, but Escalante claims there is still huge growth potential for his business in the US and elsewhere as it expands into new markets and gaming genres.

VGW has clinched a deal with the global toy giant Hasbro to develop a match-three online game (where players win when three tiles or elements are lined up) for the world-famous Monopoly board game brand. It has also purchased a minority stake in lottery operator 99 Dynamics, which has pushed aggressively into the US with its Jackpot.com online brand.

Yet away from the deals and beneath the glitz and glamour is a serial entrepreneur who went from flipping burgers at Hungry Jack’s as a teenager (the burger chain’s billionaire owner, Jack Cowin, calls Escalante his “most successful alumnus”) to undertaking actuarial studies and economics at Sydney’s Macquarie University. Later, there was a stint collating financial planning documents for clients.

That was after the attempt at Christian video games, which ended with that big debt and Escalante wondering just how he would dig himself out of his financial hole.

His breakthrough about 16 years ago was developing the idea that would become VGW. It was a combination of his love for the globally popular World of Warcraft online roleplaying game, a poker game he’d play over the internet from Perth every week with a couple of old mates across the country in Melbourne, and the Club Penguin virtual world game that Escalante watched his niece play.

The 2025 edition of The List – Richest 250 is published on Friday in The Australian and online at richest250.com.au

“I thought, ‘what if you could have a virtual Las Vegas, have a little avatar and walk around The Strip with friends?’, he says. “So VGW was to put gaming, ie gambling, inside a virtual world. That’s why we called it VGW.

“I went and did a whole 50- to 60-page business plan on why something like that should exist, and then went and raised about $1m from family and friends, and that was enough to get me started and build a virtual world.”

It has been a rollercoaster ride for VGW and Escalante ever since.

The start of VGW

VGW was started in 2010 from shared office space on Perth’s St George’s Terrace (both that building and the Hungry Jack’s at which Escalante worked are now visible from his high-rise office), where he remembers sitting next to employees from a US startup called Uber.

Escalante raised about $14.6m from investors in five years, and then tried to float VGW on the ASX in early 2016 in a mooted $3.5m deal via the shell of then-listed Synergy Plus. But the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) placed a stop order on the deal due to doubts over VGW’s legality in Australia.

Escalante also survived his entire board walking out on him in 2014 due to – according to VGW’s annual report that year – a “disagreement between the managing director (Escalante) and the other members of the board in relation to future funding arrangements and strategy”.

There’s been a string of legal battles in the US, where VGW has faced accusations – which it has consistently denied – of operating illegally in a handful of states. In 2022, it paid $11.75m to settle a class action in Kentucky, but did not admit any wrongdoing. Delaware authorities told it to stop operating there, as did Michigan.

A lobby group representing casinos and gambling companies (VGW’s competitors), the American Gaming Association, claimed last year that sweepstakes casinos were exploiting ambiguities in state gambling laws.

There was even a 2023 appearance in the Magistrates Court in Melbourne for Escalante himself, due to his being caught with a small quantity of party drugs after flying into Melbourne’s Jet Base airport. (He was placed on a good behaviour bond, with a conditional sum of $1000.)

Controversial profits

There have also been big profits, and handsome dividends.

One million customers now play virtual casino games inside VGW’s Chumba Casino every day. VGW users can play for free and also pay real money to buy virtual “gold coins” to enhance their casino games or poker. VGW also offers sweepstakes promotions. Entry is via “sweeps coins”, given away for free following purchases, daily logins and other methods - and are redeemable for cash across the majority of the US and Canada following wins.

Yet VGW’s model remains controversial. It makes no income in Australia and almost all its revenue is derived in the US, where critics say it has taken advantage of loopholes that means it escapes licensing requirements under which casinos and gambling companies operate.

Whatever the controversy – and Escalante points out that VGW is licensed in Malta, the same jurisdiction from which dozens of online gambling companies also operate – in less than a decade VGW has become a stunning success and made its founder immensely wealthy.

He also says he is just getting started.

The business now employs about 1500 people around the world, including about 250 each in Perth, Sydney and Toronto, and 600 in the Philippines. VGW also has a team of employees in Malta.

Escalante is a regulator visitor to all of his VGW offices, usually flying in on his $120m Bombardier Global 7500 jet.

Family background

It’s a long way from dusty Port Hedland in Western Australia’s north, where Escalante was born to immigrant Filipino parents. His mother worked for Centrelink and his father, Lorenzo, now a director of VGW, worked in computing at BHP.

“My parents were out working, so I grew up eating Vegemite. And I don’t even speak Filipino,” Escalante says with a laugh. His company now employs 600 people in his parents’ home country.

“I grew up around computers, thanks to my dad, and that’s where my interest in computer games comes from. I had a Commodore 64, played games, was into word processing and all that sort of thing.”

The family eventually moved to Perth, and many years later to Sydney, where Escalante studied at university before moving back west.

Like many Filipino families, the Escalantes are devout Catholics. They volunteered with the local St Vincent de Paul Society, and Escalante says he was the treasurer of his local chapter for eight years.

Religion also played a significant role in his first business venture. Wanting to be his own boss and having an interest in gaming, Escalante sensed an opportunity.

“It was around the time of [hit 2004 movie] Passion of the Christ,” he says. “Christian music was and still is 10 per cent of the music market, but how many games did they make for the Christian market? Almost none.

“So I wanted to create a video games business to have a non-violent video game my nephews could play that wasn’t like Grand Theft Auto, where you’re shooting people’s heads off.

“At the time I was very much into faith and religion. I was an acolyte. And around then, the Philippines had started making its own homegrown video games, so there was a confluence of factors.”

Religious roots

Escalante had saved some money from working in financial planning and bought his parents’ home from them, mortgaging it and raising $250,000 for what became White Knight Games.

He hired 12 staff in the Philippines, including programmers, artists, animators and engineers, and eventually signed a deal with a small listed NASDAQ games publisher, Red Mile Entertainment, for what became his “Timothy and Titus: Saints, Martyrs, Heroes” Christian video game.

It had two main characters, Paul the Apostle’s disciples, Timothy and Titus (also loosely based on the famous Asterix and Obelix cartoon strip series) and followed their adventures as they spread the Gospel message across the lands of early Christianity.

Instead of weapons or health points used in other games, Timothy and Titus collected love, hope and faith points to power their missions.

The then 23-year-old Escalante said in a 2005 press release: “By incorporating Christian virtues and actions in gameplay, by reinforcing Bible scripture, and encouraging players to learn from the lives of Saint Timothy and Saint Titus, we believe we are able to put Christ and His message at the core of the players’ experience.”

It was the era of computer games on DVDs and CD-Roms for PCs, and Escalante wanted to eventually turn his business into a Christian-themed franchise. But Red Mile would eventually strike financial trouble and scupper his plans.

“It played out over a couple of years,” he recalls. “They were meant to put me into Hillsong and these other mega churches, but I’d get sales reports back and see they’d done two sales in a shop in Los Angeles.

“They weren’t pushing it, but it turned out they were having financial difficulties in other projects. I owned the [intellectual property] and decided to terminate the contract. Because they’d manufactured 60,000 to 80,000 units [CDs] and I cancelled the contract, they couldn’t publish it anymore. So they dumped it all onto discounters.”

Escalante says that, unbeknown to him, Christian bookstores bought the CDs for $2 each. “They were selling, but I didn’t know about it and I didn’t get a cut of anything and I could not get another publishing contract,” he says.

By this stage he was heavily in debt and had just got married.

He remembers working on his honeymoon on the paraplanning business he had also started – “that’s the price of failure” – while also outsourcing to staff in the Philippines, and then slowly recovering financially.

“What do you do? You pick yourself up and keep working,” he says.

“I scaled up the paraplanning business and could teach other people to do that, though my heart wasn’t in it. And at the time I was still playing video games.”

His favourite, World of Warcraft, reportedly had 12 million subscribers at its peak in 2010, at the same time an online poker boom emerged.

A new business idea emerged that eventually led to the development of VGW, using some of the team that had built White Knight.

“I remember we could play World of Warcraft with 30,000 others, but we couldn’t have that $5 poker night we used to have back in Perth,” Escalante says.

From the real world to virtual

“We’d be sitting in this virtual pub in [a city called] Ironforge in World of Warcraft, but we couldn’t play poker in it.

“There would be virtual lotteries in World of Warcraft, or you could buy gold coins or levels on other sites. But not from the game developer. I looked into it and it became obvious that the world of video games I was from had never really touched the world of real money gaming, ie. gambling.”

While the virtual gaming world of the time was complex and graphically rich, online poker games looked relatively basic by comparison.

Then there was Club Penguin, the game being played by Escalante’s niece. There would be 20 zones hosting hundreds of thousands of simultaneous players, and he’d watch his niece playing shell games or racing games against others.

Escalante’s idea was to mix the complex virtual world with gaming. “I’m looking at these basic casino games, browser games like Club Penguin, and social games like FarmVille that had gone viral. So Chumba, my first casino, was combining all of these together.”

By 2013 he had essentially built what has become VGW today. He had the Malta licence but found most of his users were in the US, where online gambling was illegal. Escalante’s answer was a sweepstakes model. Some call it a loophole, but he calls it “doing things differently”.

“The way we can do this is by giving people quests, and so we give prizes. It is gamifying the whole experience,” he says. “I started innovating on different virtual currencies and came up with the sweepstakes model that we have today.”

Covid-19 lockdowns around the world provided an inflection point, as many customers were stuck at home with time on their hands.

Escalante points out that VGW’s profits have grown since then, and claims the company has matured. Despite some challenges, the company also remains confident in its compliance with laws where it operates, which he says should give payment companies and other suppliers comfort. “It has been a decade-long journey of helping our partners understand the reasons we don’t fall foul of any of these sorts of laws,” he says.

When asked about the apparent contradiction between his religious background and his life now running a huge company making money from a virtual casino, Escalante replies: “I’ve got direct personal experiences with three problem gamblers in my family and [seen] the damaging effects that gambling can have on the broader family. So it has always been a very important issue for me.”

He says people spend on gaming as part of spending on their entertainment, and that as a former financial planner he knows when spending can get out of hand.

“So for example, with what we do, you can’t actually spend more than $2000 with us before we ask you to prove your income. And we use data and AI to see spending patterns, and if we see spikes we try to make sure it’s within [customer] limits as part of their overall entertainment spending, and it’s not something that’s dangerous or unhealthy for them.”

Fatherhood and softer side

Even so, Escalante has attracted some notoriety. He is divorced, and has that Instagram account that’s constantly updated with footage of sports car rides, his new racing team, his jet trips and partying around the world.

He insists, though, that there’s another side to him, informed by personal experiences. A few years after he founded VGW, he says he watched his second child fight for life as an infant after contracting Kawasaki disease, a condition that causes inflammation in the walls of some blood vessels in the body.

“He was sick for a solid week and I watched his heart stop for a minute. The priest administered the last rites,” says an emotional Escalante.

“Honestly, after that, I don’t give a shit about anything [else]. All this shit around here could blow up tomorrow. I don’t care. It puts everything in perspective.”

It has taken many years, but his son has recovered. Escalante has given about $10m to charity in the past three years, mostly to children’s hospitals and health causes. His sister Felicia works on his philanthropic endeavours via his Lance East family office.

Is it enough to soften Escalante’s reputation? “Generally, people are pretty positive, actually,” he says. “I’m not too worried. Anyone who innovates or does something different may be labelled controversial.

“I’m just a kid from Perth with immigrant parents who grew up, had an idea, invented something and kept trying. This is my fourth or fifth business. I’m just like a lot of other people, having a crack.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout