The Rough Dymonds: How Penrite grew from a family business to $450m success

From mixing oils on a kitchen stove and doing deliveries by wheelbarrow, getting their hands dirty for nearly 100 years has finally paid off for the Dymond family who make their Richest 250 debut.

They call themselves the “rough Dymonds”.

But despite their low-key demeanour, the family behind one of Australia’s most successful, and still little-known, local manufacturing outfits, should not be underestimated.

Their oil company, Penrite, has grown from a family business that once just aspired to capture 1 per cent of market share, to about $450m revenue and strong profit margins.

Led by 52-year-old chief executive Toby Dymond, Penrite has 250 staff and produces 40 million litres of engine oils, lubricants and additives each year, mostly from a factory and warehouse in Melbourne’s industrial outer southeast.

It’s the sort of product that has, for much of the company’s history, been sold to mechanics and workshops, and car enthusiasts with deep technical knowledge. More recently, it has ridden the rise of auto-related retail outlets including Supercheap Auto and Repco to more aggressively expand sales.

All nine of the Dymond children have been involved in Penrite and of the eight still living, somehow they’re just about all still talking to each other. They have each worked in almost every job across the business; surviving and now thriving amid the gloom, and sometimes doom, that has enveloped Australia’s car industry and wider manufacturing base.

There’s not much that’s glamorous about it, as Toby Dymond readily admits: “Oil is a dirty industry. It’s not fintech or any of those new industries. A lot of people just don’t get into manufacturing because it’s seen as dirty. It’s hard work.”

Penrite will next year celebrate its 100th anniversary, while 2025 marks its 46th year under the Dymonds’ control.

It is mostly a tale of a family sticking together and surviving the tragedies, economic downturns and other threats that almost put them out of business.

“We all want Penrite to succeed. We might argue how we get there, but we have the same goal in wanting it to perform,” Toby Dymond tells The List in an interview together with several of his siblings, on a hot summer’s morning in Penrite’s small meeting room in Dandenong.

“That’s the one thing we all agree on. It’s not about the money. The money comes with the performance.”

Toby and his brother Jon, 58, Penrite’s regional sales manager, are wearing company-branded polo shirts and shorts. Sisters Fleur, 55, Penrite’s national merchandise manager, and Samantha, 53, who works in sales, are quick with a quip about the boys – especially Toby, the second-youngest.

There’s also 61-year-old Nigel, Penrite’s general manager of operations, plus Sue, 62, Julia, 57, and Roland, 50. Each has worked in the business at various stages.

Penrite’s revenue was about $30m in 2006. By 2012 it had reached $70m, and is set to hit the $450m mark this year. In 2024 it made a $53m net profit and is debt-free. Penrite owns the land its factories and warehouses sit on, and there are further expansion and acquisition plans.

“We trust Tobes and we back him. We might not agree with everything and we let him know that,” Samantha Dymond says firmly, before jokingly adding, “We say ‘thanks Toby’ all the time.”

Fleur Dymond concurs: “The numbers are talking now, right? I think if the numbers weren’t talking, then people in the room would get a bit more rowdy. At this point in time, we’re only going one way, which is north.”

Of the company’s growth, Jon Dymond gestures towards Toby. “It’s a credit to this bloke. We just can’t tell him too much …” Samantha finishes her brother’s sentence: “ … otherwise his head gets too big.”

It’s at this point that the siblings start laughing and joking about each other, not wanting to let any ego in the room get out of control.

Penrite is rolling now, but it was a business that lost its way for a time, only to start accelerating again after the Dymonds took back management control. It has since evolved from a firm that was content to concentrate on the technical aspects of mixing oils, to a company now more focused on retail channels and growing market share.

Margaret Dymond, the 93-year-old family matriarch, succinctly tells The List in a later interview at the family’s classic car museum: “If you don’t grow, you go.”

Yet none of it would have happened if Margaret, who was busy looking after her then-nine children ranging in age from primary school to early 20s, hadn’t spent weeks convincing her late husband John “JD” Dymond that he couldn’t turn down what would turn out to be the opportunity of a lifetime back in 1979.

Margaret still sets the family culture, having brought up the children in austere surroundings in Melbourne’s suburbia. If the children wanted money, they had to work for it. With nine children, there were few luxuries, but Margaret was careful with money and in those pre-capital gains tax days, put savings into buying and selling some real estate, making modest profits that helped with the Penrite purchase.

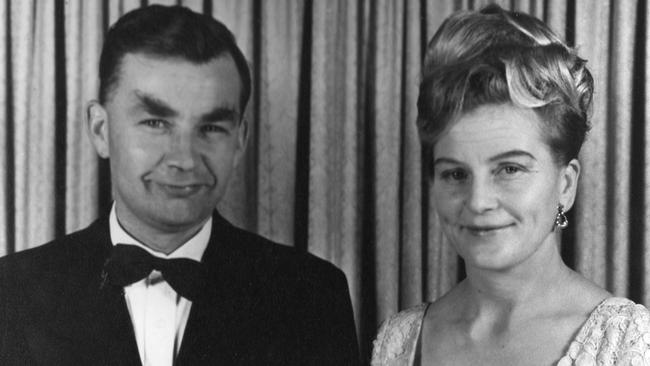

Margaret and John Dymond moved to Australia from the UK in 1958, where John had started as a 16-year-old apprentice at Vauxhall Motors in Luton and gained a mechanical engineering degree at night school.

He went on to work for BP in its technical department, helping to develop lubricating engine oils for harsh climates in Malaysia, Papua New Guinea and Australia’s north, and then for the Australian arm of an American speciality additive company, Lubrizol.

It was there in the 1970s that John met and became friends with Les Mercoles, who had started mixing oils on his mother’s kitchen stove in Melbourne’s St Kilda, and in 1926 started the Penrite Oil Company.

As an aside, the origin of Mercoles’ lubricants was Pennsylvania (Pen), and he declared he would only sell the right (rite) oils – hence the name, Penrite.

Mercoles had started delivering his oils by wheelbarrow to local petrol stations and factories, and would eventually move across Melbourne to East Brunswick. The business was small and mostly sold its products around Melbourne.

By 1979, Mercoles was in poor health and with no family to succeed him in the business, wanted to sell Penrite. He offered it to John Dymond, who said no for about six weeks – before Margaret stepped in.

“He wasn’t a gambler, he wasn’t a risk taker,” she remembers. “So I said to him, ‘You’ll never have a better opportunity and you’re crazy if you don’t take it. I’ll back you all the way.’”

Lost in the sands of time is the purchase price, but son Roland Dymond estimates it may have been the equivalent of about $100,000, given all the family properties were mortgaged and his mum’s “beach shack” was used as collateral on some vendor financing provided by Mercoles.

“It was paid off about five or six years later,” Margaret recalls. “We put everything on the line. But that’s what people do.”

John Dymond was able to utilise his technical acumen and was finally in charge of his own destiny, although the business had only eight employees. “We were probably world famous in Brunswick,” Toby Dymond says with a wry grin.

Everyone in the family pitched in. Sue Dymond remembers running accounts from a small office attached to the workshop next to where her dad mixed oils, and many of the kids would spend Friday nights at home packing invoices in envelopes, ready to send out on Monday.

The boys were soon using the old company truck, a 1963 Bedford, to deliver oil, says Jon Dymond. “You’d have to roll a [44-gallon] drum off the back onto an old tyre on the ground. Things were a bit different in those days.”

All the children remember cleaning up oil spills, filling bottles, meeting customers and helping with sales. Fleur Dymond says they were a constant presence in the small workshop where research and development was rudimentary, even if their father was an expert in his field.

“Someone would bring in a sample of oil and he’d say, ‘One moment, I’ll go take it to the chemist.’ He’d walk out the back, put the white coat on, and go to the kitchen bench. That was the lab; the chemist part,” she recalls.

Later, when the family moved to a bigger factory in Melbourne’s Wantirna South in 1997, eldest son Mark Dymond designed and helped build the pipeworks for the oils to be pumped from tanks to the areas where they were mixed and blended, and then transferred to loading docks. Roland Dymond, an engineer by trade, also helped.

The 2025 edition of The List – Australia’s Richest 250 is published on Friday in The Australian and online at www.richest250.com.au

In 1981 John Dymond designed a new higher-performance range of oils specifically for Australia’s uniquely harsh driving conditions. Sales began to grow, though still mostly to mechanics, car racing teams, car club enthusiasts and others whom the family met racing or via their father’s passion for vintage cars.

A Brisbane mixing facility and more warehouses would open around the country, but Samantha Dymond still recalls retail relationships being rudimentary when she started in sales in 1998. Visiting one big store, she was told they hadn’t seen a Penrite representative for a couple of years, and she had to walk past rows of rival products to arrive at a small Penrite display.

It’s at this point that the family’s story takes a twist. Mark Dymond died of cancer in 2002, aged 42. With a tear in her eye, sister Fleur recounts that “Dad lost his mojo for a while” after that.

John Dymond died four years later at 75, and it was during this time that the Dymond family felt the company was drifting under non-family managers. They staved off a management buyout offer, and had previously survived unions picketing their factory in an effort to unionise delivery drivers.

Toby Dymond estimates the business would have been worth about $20m, and points out that while “sometimes the family gets a bit offended … the numbers were pretty average”.

Penrite was also selling “white label” oil for other brands and the management was conservative, a mentality which probably stemmed from John Dymond’s desire to maintain a more premium brand for knowledgeable and passionate mechanics and enthusiasts, rather than chasing mass market sales.

“I joined the board in 2006 and I remember trying to set what I thought were quite realistic budgets, like 10 per cent growth,” Toby says. “I’d be told that was ridiculous. But it was going from $30m to $33m!

“They were very internally focused. They were very product-focused, not customer-driven. There was a credit policy where if a customer bought a bottle that was leaking, there was no refund. Little things like that. There was outsourcing, and we had to have some honest conversations because (the family) didn’t really know what was going on.”

At this point, there were some Dymond family members working in the business, but not at management level.

While his mother wasn’t thrilled, John had told Toby he should work elsewhere and learn about business outside the family firm. Toby worked at General Motors, and then in banking and consulting, before joining Penrite in 2011 in a leadership role alongside brother Nigel. The Dymonds were back in charge.

“We sat down as a family and we could see it very slowly doing this,” says Jon Dymond, gesturing downwards. “So we thought, if it was going to go down in burning flames, it may as well be with us in control of the boat.”

Toby Dymond took over as full-time CEO in 2020 and is a disciple of the Six Sigma management system that aims to reduce waste and costs in business processes, while also focusing more on the customer.

Penrite has expanded its product line in the past decade, manufacturing about 230 different products across nine branded Penrite lines for use in cars, boats, motorcycles, trucks, tractors and other machinery.

A large chunk of sales is now in smaller bottles of oil, plus brake and steering fluids, which are sold in retail outlets rather than just supplying bulk drums to mechanics and car shops.

In 2016 Penrite moved to its current Dandenong facility, a former Smith’s chips factory, where manufacturing processes are mostly automated and there is a large warehouse facility. The walls of the head office are lined with memorabilia, from racing car liveries to old factory photos and former advertising campaigns.

The family has knocked back approaches from other oil companies and overseas buyers. Having come this far, says Toby Dymond, they want to stay in charge.

The next phase of Penrite’s growth, he says, will be to look at adjacent parts of the market including fuel, brake pads, shock absorbers and other automotive products. That may involve bolt-on acquisitions and be part of a strategy to deal with the looming challenge of growing electric vehicle sales.

All of the Dymond children are passionate and knowledgeable about cars, and still turn up at car club meets and races. Samantha still races a classic Lola MK1 model that, at more than 60 years old, has been around longer than she has.

Many of the siblings have restored old cars at a museum they have established at the old factory in Wantirna South, where they have hosted club events and customer nights, and even a wedding reception.

It is one of Margaret’s favourite spaces, with a library dedicated to her late husband and another area built as a tribute to Mark and his passion for motorbikes.

The family also has extensive property holdings, including the land that Penrite’s mixing factories and warehouses sit on.

There’s also a big family holiday every two years. Last year, about 40 Dymonds holidayed in New Zealand together. They joke that a Venn diagram of the overlap between family and work talk on that trip would be “just about right”.

It’s not perfect, but they agree they try to make it work. Like Penrite’s history, it has required time and effort.

“It’s taken us 100 years to get to this point, and let’s be honest – the growth has probably accelerated only in the past 15 years,” Toby says.

“People think it’s an overnight success in a way, but that overnight success doesn’t happen without a lot of hard work along the way.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout