Regulators to focus on shadow banking

THE attention of financial regulators will now turn from the banks to market-based finance.

THE attention of financial regulators will turn from the banks to market-based finance and other forms of “shadow banking” over the next year to ensure that risks are understood and potential threats to global financial stability are managed.

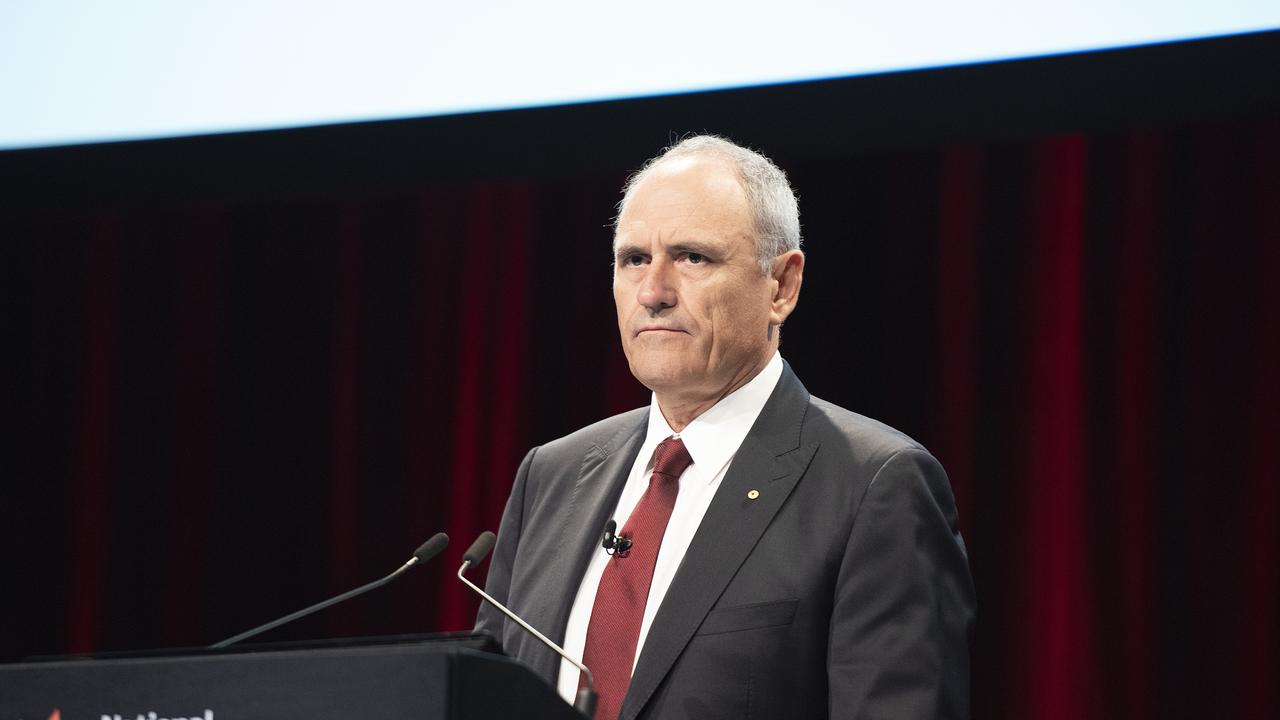

The governor of the Bank of England and chairman of the Financial Stability Board, Mark Carney, told The Australian efforts to strengthen the banks had not simply resulted in shifting risk to the non-bank area, but it was important to understand what those risks were.

Mr Carney said the G20 had agreed on the major elements of the financial reforms that had evolved since the 2008 financial crisis, although there was still substantial work on implementation to be completed.

Mr Carney said Australia had set an ambitious G20 agenda in completing the major outstanding areas of financial regulation within a year, with the biggest challenge being measures to ensure that a failure among the 30 globally significant banking groups could be resolved without recourse to public funds.

This has included new definitions of “total loss-absorbing capital” and also agreements that, immediately after authorities seize control of a banking group, counterparties cannot liquidate their collateral under derivative agreements.

Describing this as a “watershed moment”, he said the Financial Stability Board would now spend a year getting stakeholder feedback and making sure that the new scheme worked for each individual bank. “At the end of it, inevitably with these things you tweak it one way or another, but in broad-brush, we will finalise that across the year,” he said.

Mr Carney said that beyond implementation of this and other parts of the reform package, including the introduction of new leverage and liquidity ratios, the Financial Stability Board would be focusing on identifying risk elsewhere in the financial system.

“What we’re doing over the course of 2015 is looking at what shadow banks themselves might be globally systemic.” The FSB would be looking at what activities were of such size and complexity that they could also contribute to global financial instability.

Mr Carney said shadow banking, including market-based finance, played an important role. “This could be a force for good. It could build diversity into the system. Diversity brings resilience and it brings competition.”

He said that when risk moved from one part of the financial system to another, it was taken up by people with different funding bases, risk preferences and time horizons.

However, the financial crisis had shown that regulators did not understand how tight the connections between banks and shadow banks were.

“A lot of them were implicit, a lot of them were off balance sheet and a lot of them just hadn’t been fully thought through,” he said.

“When the crisis hit, all these shadow banking risks collapsed back on the centre.”

The FSB had been focusing on protecting the centre with capital and leverage ratios and controls on liquidity, but now had to understand better the risk dynamics outside the banks.

Each country has been asked to review the regulatory perimeters surrounding the shadow banking system, which takes different forms in different countries.

Shadow banking is included in the reforms agreed to at the G20, particularly with controls on the charges or “haircuts” on transactions with non-banks in repo markets, where assets are used as collateral for cash.

“(Repo) markets go through bouts of euphoria and despair and they are very pronounced and were really one of the big amplifiers of the crisis, so we’ve gone in and provided some regu-lation,” Mr Carney said.

Mr Carney said there was still work for domestic banking regulators to ensure their banking systems were able to managing bank failures without recourse to public funds.

He said he did not expect this to result in the standards being applied to the globally significant banks filtering down to large local banks, such as the big four Australian banks.

Those standards had been devised to stop failures causing global instability. “There is a fundamental unfairness to being too big to fail,” he said.

“Where it comes into play in Australia is that someone that is globally too big to fail gets the benefit of an implicit subsidy from their home country authorities.

“They can borrow more cheaply in global markets and it is effectively subsidised competition when they come into a place like Australia.”

The new regulation of these 30 global institutions was designed to remove that subsidy.

It was up to domestic regulators to have resolution plans for the failure of domestically systemic institutions.

Mr Carney highlighted the new leverage ratio which requires banks to hold capital equal to at least 3 per cent of total assets, irrespective of risk weighting.

Although Australian regulators were not enthusiastic about this aspect of the global financial reform, Mr Carney said it had been vital when he was governor of Canada’s central bank during the crisis.