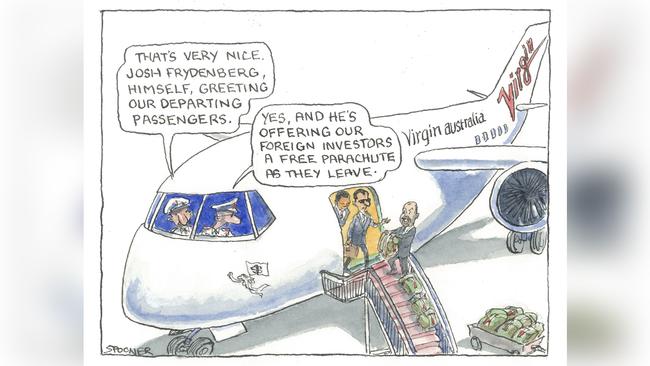

News that Virgin chief Paul Scurrah has his hand out looking for $1.4bn in loan guarantees came with confirmation from Josh Frydenberg that he wanted two airlines in place when the crisis ends.

The problem is, when will the crisis end, how is Canberra going to turn off the tap when it does, and what sort of plan is in place to ensure Australia is actually a much better place than when it entered the coronavirus mess?

Bailing out airlines does not seem a great place to start, but this said, some smart policy folk in Canberra say we need just that because this time it is different.

Qantas boss Alan Joyce would no doubt not object to Virgin getting $1.4bn if that meant he would get $4.2bn, being three times bigger.

In the first half, Virgin made $24.5m on $3.1bn in revenue and Qantas $771m on $10bn in revenue. What neither would enjoy are the conditions that should be attached to any debt guarantee.

One assumes it would be a subordinated convertible note ranking behind senior debt but ahead of the equity holders, which means if the debt was not repaid then Canberra gets a big equity stake in the company.

Presumably this wouldn’t suit Scurrah’s shareholders, who control more than 90 per cent of the company and include troubled carriers such as Etihad and China’s HNA along with Singapore Airlines, which has just raised $S9bn ($10.2bn) in equity. This is more than enough to buy Virgin, but others say it is more focused on its own survival, and few have ever picked its future strategy.

The strings attached to the arrangement may convince Singapore it should come to the party and take control of Virgin, which would be Scurrah’s moonshot deal — a dream come true.

Talk of a bailout then maybe helps Scurrah get his share register in order.

When the US government gave a $US10bn ($16.2bn) line of credit to Delta as part of a $US100bn bailout package, the debate quickly turned to limits on executive pay, among other controls, because in America top 50 company bosses earn 1000 times that of their average workers.

In Australia the gap is more like 66 times, but hey, if the taxpayer is paying then let’s cut that ratio back.

Virgin says it doesn’t need the money now, but may do, and it wants the deal to be a $5bn industry aid package that takes into account the fact tourism accounts for 8 per cent of the economy.

The government bailout package so far works because it is aimed at helping those who need it, in creative terms economy wide, and that should remain the thrust.

Giving Virgin special deals makes no sense — its costs in round terms include staff at 20 per cent (they are all largely gone), fuel at 20 per cent (but no planes means no petrol), lease costs at about 10 per cent and finance costs on the expensive $5bn in debt around 10 per cent.

As things stand until revenue picks up, there is cash to pay some bills and arrangements in place for the banks and other creditors to go easy, which means Virgin and the government should stick well clear of any deal.

Cashing in on Coles

Coles chairman James Graham spent 20 years on the Wesfarmers board before assuming his present post and no doubt was unimpressed when his old colleagues trashed his stock price, selling another 5 per cent of the retailer to raise about $1bn, sending the stock price down 9.9 per cent to $15.16.

Coles has become a “nice to have, not must have” part of the portfolio, which means when the two-month imposed restriction expires the market will be betting on the imminent sale of the final tranche.

In all, Wesfarmers has raised just over $2bn selling Coles shares and in the process reduced debt to $500m.

Balance sheet flexibility in the present uncertainty is the prevailing wisdom at the Swanbourne Beach head office of Wesfarmers.

The company faces some risks of its own if Australia follows New Zealand’s example and shuts down Bunnings to just trade buyers and closes Target and Kmart, but so far Wesfarmers argues they are all essential services (a stretch).

Inevitably now the company is cashed up, attention turns to who it might buy, but that is a trade for others to play, other than to note it has the firepower, but the trick is to convince targets to sell in this sort of market.

Banking on a party

The ASX has come to the party for big-end-of-town investment banks with temporary rule changes that make it easier to talk big companies into raising money.

The trick for company boards is to consider the interest of all shareholders because the ASX has opened the gates for them to be buried. Post-GFC corporate Australia raised about $100bn, 45 per cent of which was by way of placements and the investment banks pocketed $2bn fees, with UBS picking up the lion’s share.

The key changes unveiled on Tuesday include doubling the number of days you can stay in a trading halt to four before the five-day suspension comes into effect, an increase in the limit on how many shares can be placed with the house fund managers from 15 per cent of issued capital to 25 per cent every 12 months without the need for shareholder approval, and no limit on how many shares can be issued under a renounceable rights issue.

By way of explanation, the house fund managers are those managers included on the investment bank’s list of best friends to put issues away.

Most small shareholders would prefer renounceable issues, which mean unwanted rights can be sold, but this package is weighted heavily towards the house fund managers.

After the GFC this group took deeply discounted shares to recapitalise corporate Australia and then made out like bandits when the stock prices rose.

The increase in the placement amount requires a follow rights issue or share placement, which could by way of example be a token issue after handing control to a new 20 per cent shareholder.

Whether this happens this time remains to be seen but the warning bells are ringing loudly.

Parity in motion

Amid the market mayhem a rare threshold was crossed last month when the New Zealand dollar was valued more highly than the Aussie, with the latter trading on March 17 at NZ99c, before rallying to NZ102c on Tuesday.

Parity parties were the talk of the town across the ditch back in 2015, when parties were allowed.

Get ahead of the game

The main planks of the government survival strategy are now in place, part of which is the national co-ordination commission under former FMG boss Neville Power.

Terry Moran from the Centre for Policy Development argues the time is right now to look through the crisis into the recovery with the assumption that not every company will stay on the government’s bridge to recovery.

Moran would like emphasis on issues such as increased vocational training to retrain displaced workers, a new system for employment services to help people find jobs, boosting medical equipment manufacturing — including testing devices for viruses like the coronavirus’s next reincarnation — and increased digital know-how to help build new industries.

The time for this sort of thinking is now.

A federal government bailout of Virgin Airlines is a step too far in what has to date been a well-constructed recovery plan from Canberra.