Advertising campaign prompts uptick in testing for hepatitis C

An advertising campaign to raise awareness for hepatitis C testing offended some, but had the potential to save lives. One of its creators told The Growth Agenda the creative “risk” was worth the controversy.

An advertising campaign created to raise awareness for hepatitis C testing in New Zealand last year offended some audiences to such an extent it was pulled off air. But the controversial creative approach was “an easy risk to take” because of its effectiveness, according to one of its creators, group executive creative director at ad firm VMLY&R New Zealand, Kim Pick.

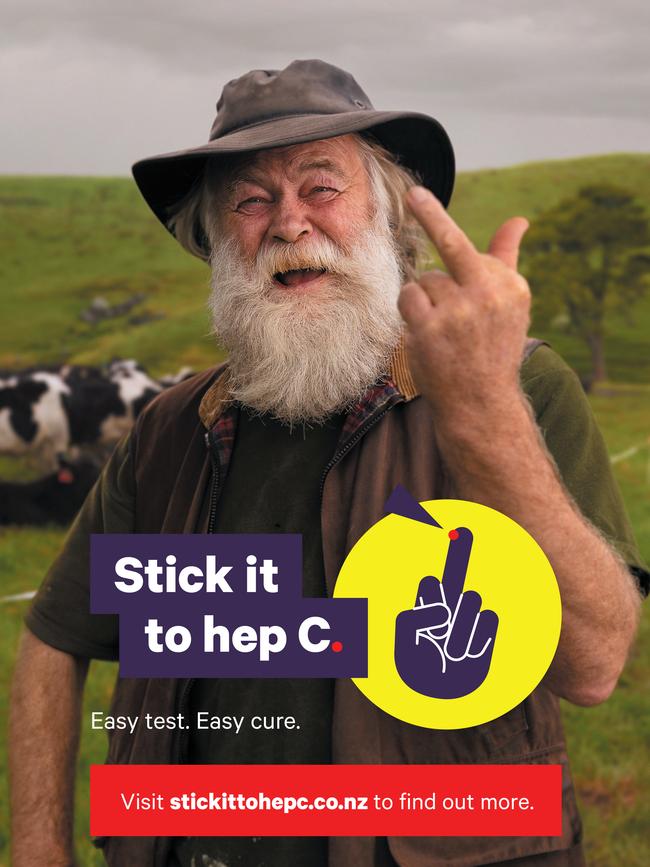

New Zealand’s Ministry of Health engaged VMLY&R New Zealand to develop a TV advertisement as part of the campaign titled “Stick it to Hep C”, which aimed to encourage testing for hepatitis C.

The campaign became the most popular advertisement in New Zealand in August and September of last year, according to media monitoring platform MLME Media Analytics, and reached 89 per cent of its target audience within two months.

It boosted hepatitis C testing rates by 150 per cent.

Positive tests also rose by 1000 per cent, which enabled at-risk individuals to receive treatment.

The TV advertisement, which first aired ahead of World Hepatitis Day on July 28, 2022, featured a series of individuals cheerfully raising their middle finger to others in everyday settings, flipping what is often considered an offensive gesture into a humorous and positive one.

That same gesture provided a visual segue to demonstrate how to get tested for hepatitis C, which consists of a finger prick test.

Speaking at a Growth Agenda event at Advertising Council Australia’s Festival of Creativity in August, Ms Pick explained: “The safe option, in this instance, was actually the deadly option. Safe messaging wasn’t resonating.”

Two months after the campaign was aired on TV, the Advertising Standards Committee received 19 complaints and ordered the advertisement off-air.

However, the bold creative approach had already made its intended impact. It earned the attention of its target audience – and the media in New Zealand and abroad, reaching as far as France, Ireland and Italy.

The New Zealand Herald also ran a poll asking its audience whether they found the campaign offensive. Only 35 per cent said “yes”, while 65 per cent said “no”.

The ruling was overturned on appeal, and the video was allowed to return to air in November 2022 in the interests of “natural justice” and for its role in addressing a national health crisis.

At the time, it was estimated that around 50,000 people in New Zealand potentially had hepatitis C, but didn’t know about it, as infected individuals can remain asymptomatic for decades.

The disease is the leading cause of liver cancer in Aotearoa, New Zealand and causes approximately 200 deaths per year.

When deciding on the creative approach, Ms Pick said that the Ministry of Health and VMLY&R worked together to assess the potential risk associated with a gesture that was considered “vulgar” by some. They concluded the potential to save lives far outweighed the risk of offending some.

“Working with government and doing something that felt (creatively) unsafe was actually quite risky,” said Ms Pick. “We were only able to do that with a lot of robust research in consultation with the community.”

Prior to launching, the advertisement was assessed by the Commercial Approvals Bureau as being “unlikely to cause serious or widespread offence”.

Research conducted by analytics company Kantar Public for the Ministry of Health also found that only 19 per cent of people found the use of the middle finger “unnecessary” or “offensive”.

Most reactions were “actively positive” and thought the campaign was “funny, distinctive, interesting and involving”. These insights, combined with the fact that the campaign had the potential to save many lives, made the decision clear.

“(It was a) risk, sure. But there was no way morally we could have done something ‘safe’ because lives would have been lost.

“Weighing up mild offence to some, versus cut-through and connection to those who needed it was an easy risk to take,” Ms Pick said.