Just over two decades ago, the fuel refining industry, operating eight refineries across the nation, supplied about 95 per cent of the petroleum products needed by the domestic market.

A federal government report at the time flagged headwinds ahead, warning “capacity expansions or new refineries being brought on stream in a number of Asian countries” had generated an oversupply, and with it, increasing import pressures.

Give the author a belated gold star.

Fast forward to the current day and, according to the government, we now import around 90 per cent of our liquid fuels.

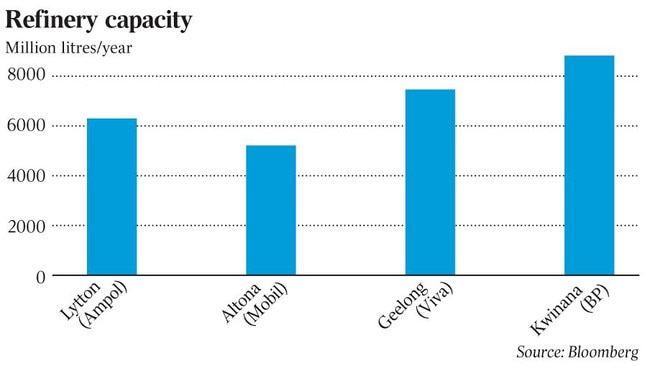

Since 1999 we have slipped from eight operating refineries to four, with our largest, Kwinana in Western Australia, due to close and be converted into an import terminal because, owner BP says, “regional oversupply and sustained low refining margins mean the Kwinana Refinery is no longer economically viable’’.

Our three remaining refineries are on taxpayer-funded life support, and all of them put together produce less refined fuels than a single producer in Southeast Asia does.

Federal Energy Minister Angus Taylor announced an $83.5m “production payment’’ this month to tide the local refiners over until a longer-term plan kicks in from July 1, 2021, and $200m is being invested in a competitive grants program to build additional onshore diesel storage.

What this longer-term package needs to be directly aligned to is Australia’s liquid fuel needs over the next two to three decades, in the event that supply from overseas is severely curtailed or even cut off.

While every developed nation on the planet seems on an inexorable path towards a land-transport sector powered by renewable energy, for a long time to come our mining, agriculture, freight, and importantly military vehicles will be heavily reliant on liquid fuels, most of which we import.

Should Australia find its major trade routes to Asia and the Middle East compromised, an inability to refine oil, and importantly our own oil, would be a big problem.

During the debate over drilling for oil in the Great Australian Bight off South Australia — an endeavour which Norwegian company Equinor binned in February this year — much was made by former federal resources minister Matthew Canavan of the importance of the project to the nation’s fuel security.

More oil would be great — we currently don’t produce as much as we use. But if we can’t refine it here anyway it’s not much use to us in a situation where supply lines of refined fuels are cut off.

And if that happened, until recently we had just weeks worth of supplies of petrol, diesel and jet fuel held locally.

A government report on our fuel security published two years ago found “Australia holds 18, 22 and 23 days of consumption cover for petrol, diesel and jet fuel respectively’’.

The most recent Australian Petroleum Statistics report showed we had 25 days worth of automotive gasoline on hand in October this year.

Our redundancy in this area has been — in theory — upgraded this year, with the federal government announcing in April it would spend $94m to build up a strategic fuel reserve. But the gaps in our fuel strategy were laid bare by the fact that we have to store it in the US until enough storage capacity is built locally.

Having such low fuel stocks also fails to fulfil our obligations under an agreement with the International Energy Agency that we hold at least 90 days’ supply.

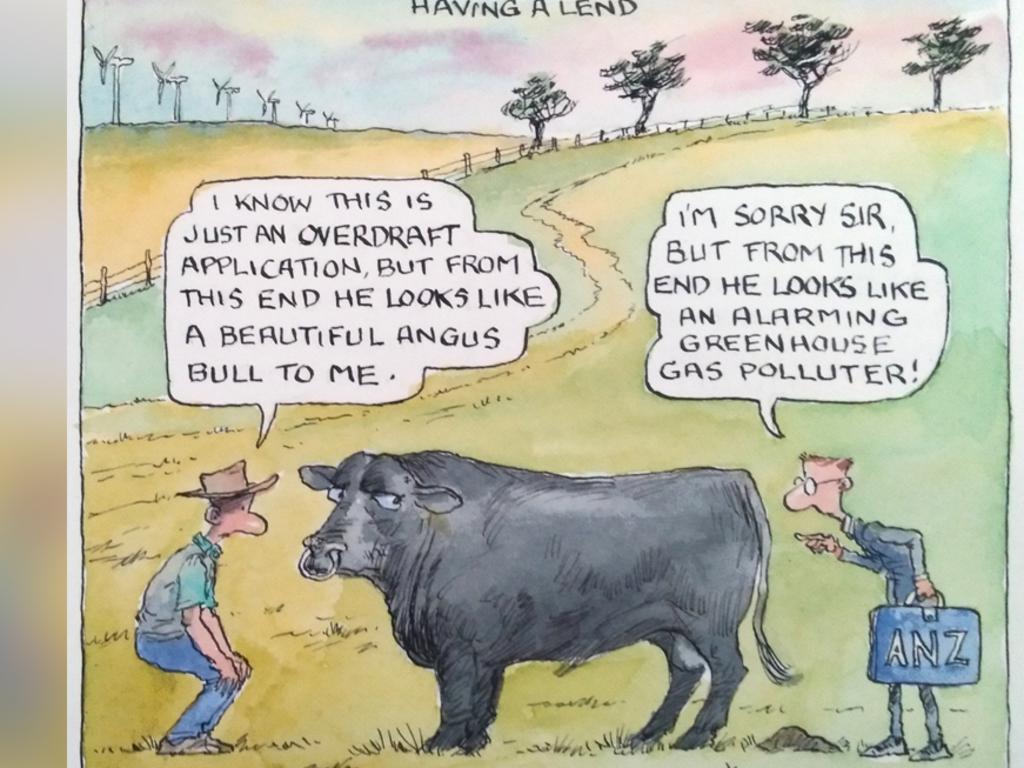

In the debate about refining, Australia has, as in other sectors, pursued the ideology of the free market and globalised free trade to a fault.

The same report which set out our paucity of local fuel stocks put it as well as any. “Australia is an outlier in the global community in the way we think about liquid fuel security,’’ the report says.

“When we consider countries of similar economies, most see fuel security as part of their strategic capability and take steps to manage fuel security with that in mind.

“Australia, by comparison, has chosen to apply minimal regulation or government intervention in pursuit of an efficient market that delivers fuel to Australians as cheaply as possible.’’

Cheap fuel is great, until your ability to purchase fuel on the open market dries up.

The longer-term policy around refining capacity and fuel security must countenance this possibility.

The Australian fuel refining industry can’t be allowed to sputter out the same way our car manufacturing capacity did, or the very security of our nation could be at risk.