From plans to import beluga sturgeon to harvesting Murray cod, Australia’s next luxury food

Russia’s war in Ukraine has opened the door for local caviar producers to take on the traditional luxury markets of Europe and beyond.

Griffith – the heart of the NSW Riverina – punches above its weight when it comes to serving up Australian culinary delights.

It is home to McWilliam’s Hanwood Estate, known for its $20 bottle of classic tawny port. De Bortoli’s Riverina base is a stone’s throw away in Bilbul. Then there is the region’s illicit past of producing cannabis among the orchard trees.

But now lurking in ponds closer to town is Australia’s only farmed Murray cod.

The fish’s white flesh, which has none of the earthy taste of the wild cod, has won praise from chefs across the country from The Atlantic in Melbourne to Aria in Sydney – and even overseas with celebrity chef Heston Blumenthal endorsing the brand.

And it is those chefs who have sparked demand for another Australian first product: Murray cod caviar.

Australia is eager to develop a homegrown caviar industry and the federal government is beginning public consultation to potentially allow for the live importation of sturgeon.

Salmon producers have also been getting in on the act. Their fish produce a glossy red roe that’s larger and has more pop than the fine black balls of Caspian varieties which Russia has traditionally dominated.

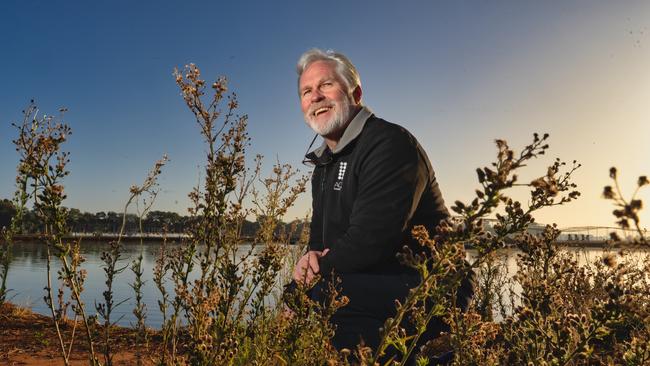

Ross Anderson, the chief executive of ASX-listed Aquna Murray Cod, believes caviar produced from what is often cited as Australia’s national fish will sit somewhere in between, in terms of pricing and prestige.

Aquna is launching its own range of caviar, which will initially be available to chefs in the wholesale market before branching out into retail.

While it is a niche product, with production in the hundreds of kilograms versus thousands, it allows Aquna to extract more value from its Murray cod.

“It can double the return we get out of a female fish,” Mr Anderson said.

“It can be anywhere from a 50 to 100 per cent increase in the value of the fish, depending on the spawning and the size of the fish as well.”

Therefore, producing Murray cod caviar may seem like a no-brainer for Aquna. But when it considered the move, the company – which listed on the ASX 12 years ago – faced a problem.

To grow caviar, Mr Anderson and his team needed to sex its fish, holding back females so they could grow to a sufficient size, so their meat and roe could be harvested at a commercial scale.

Aquna has been struggling to fill demand for its Murray cod and has withdrawn from some international markets, including Japan and Europe, as it builds new ponds and works to increase supply, which it forecasts will hit 10,000 tonnes a year by 2030.

“One of the changes we made was we went through the process of sexing the fish and holding back females, which has actually contributed to a shortage of fish over the past 12 months,” Mr Anderson said.

“But, it (caviar) is really fitting with our idea of sustainability and value adding because we’re using more of the fish. And it fits in with the idea of Aquna being a luxury food brand.”

International restaurateurs are increasingly valuing Australia’s ability to produce luxury food that matches or exceeds traditional markets. For example, Australian-grown black truffles are finding their way on to the menus of Michelin star restaurants in Europe, where their “down under” provenance is celebrated and commands a premium.

As Mr Anderson opens a jar of champagne-coloured Aquna Gold caviar, he knows the product has similar potential but is not getting ahead of himself.

“We’re going to take it one step at a time. The first step is to introduce it to the Australian market and let them say what a beautiful, high-quality product that it is,” he said.

“Then have some international visitors taste it and see what it’s like, and then over time as it develops and grows we can introduce it to the world. We’re going to take baby steps before we try to run.”

Aquna’s caviar project began when Lisa Downs, a sales manager at top caviar importer and distributor Calendar Cheese, saw some chefs serving Aquna’s cured roe and fish. She then approached Aquna’s head of business development, Ian Charles, at the Boston Seafood Expo a couple of years ago about a partnership.

Agribusiness deal-maker and corporate adviser David Williams believed Murray cod caviar had potential. Mr Williams advised Canadian seafood giant Cooke in its $1.7bn takeover of Tassal last year and has been promoting the importation of sturgeon caviar.

“It (Murray cod caviar) is a value-added product that will be highly valued among chefs to be served alongside salmon roe,” Mr Williams said.

Earlier this year Mr Williams said 2023 was all about bringing caviar to a wider audience, with the $300 jars of the product – synonymous with luxury and extravagance – being previously off limits to all but the very wealthy. Now he says it has surpassed yellowtail kingfish as the on trend entree.

“It’s everywhere in bite-sized, affordable dollops,” he said, adding that Qantas even served it on a flight to New York earlier this year. “Caviar is the new black,” he said.

Despite appetites for caviar increasing, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – which now spans more than 500 days – has disrupted global supply. Western countries have banned Russian caviar imports and another of the country’s specialities, vodka. While most Russian caviar is consumed by Russians, in 2021 the European Union alone imported about 1.7 million euros ($2.8m) of caviar from Russia.

Now, citizens on the continent are banned from having a dollop – opening the door for producers of sturgeon caviar. Italy, France and Poland as well as China are ramping up supply – as well as alternatives, such as Aquna’s product.

Overall, the global caviar market is worth about $US276m ($400m) and that is expected to soar to $US1.88bn in the next five years with an annual growth rate of 9 per cent, according to Market Data Forecast.

For Aquna it cannot bring on extra supply of Murray cod caviar flesh and caviar soon enough, as it experiences wild swings in its share price. While its stock has surged 11.5 per cent to 14c in the past month, in the past year it has fallen more than 34 per cent.

Its revenue jumped 25 per cent to $6.1m in the six months to December 31, and the company cited more fish available to be sold and at a higher price per kilogram.

Meanwhile, it slashed its half-year loss from $3.04m to $365,000. Retail prices for Aquna’s Murray cod are around $65 a kilogram – almost twice that of salmon.

The company now has 50 ponds and plans to build another 79 – 50 of which will be commissioned this year.

“They won’t all be grow-out ponds, some of them will be juvenile ponds,” Mr Anderson said.

“So as time goes forward we will move into this free-range model with our fish, and more and more of our ponds with pens in them will turn into ones holding juveniles.

“Production looks great ahead of us. We have a lot of fish in the water. But our problem is that it takes two years to grow a fish.

“So, while we have many, many fish in the water we don’t have enough saleable sized fish to supply demand at the moment.”

And he expected the conundrum to continue, even as the company rapidly commissions more ponds.

“If you look at a fish like salmon, more than four million tons of it is produced in the world every year and it all gets eaten,” Mr Anderson said.

“If you look at Patagonian toothfish, last year there were 24,000 tonnes of that harvested and it all gets consumed at premium prices.

“So what the cap-out demand for us is with our pricing, I don’t know yet; but we’ll push it all the way until we find that out.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout