Compulsory super needs to be protected, not raided: Greg Combet

The industry superannuation sector is putting pressure on the Albanese government to protect compulsory superannuation from more raids in the future.

The industry superannuation sector is stepping up pressure on the Albanese government to protect compulsory superannuation from raids by future administrations.

As it marks the three-decade anniversary of the introduction of compulsory super scheme, there is concern in the industry that moves by the former Coalition government have paved the way to open up super for a range of uses, including buying a first-home and other social needs.

Starting in 1992 at 3 per cent of wages, compulsory superannuation in Australia is now set to rise from 10 per cent to 10.5 per cent on July 1.

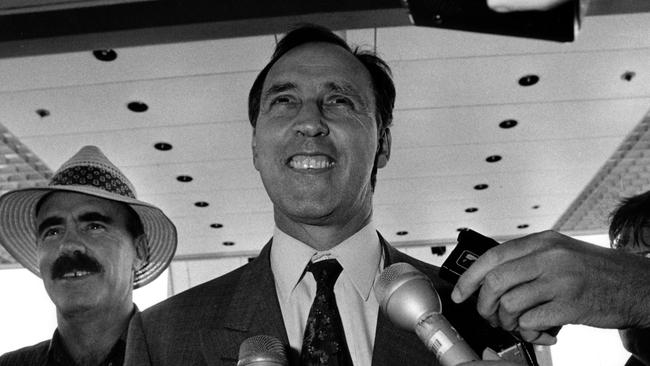

“If you start opening it up, like Morrison did during the pandemic and like he suggested during the election campaign, it erodes the objective of superannuation and undermines members’ interests,” the chairman of Industry Super Australia, Greg Combet, said in an interview with The Weekend Australian.

Mr Combet, who is also chair of the $185bn IFM Investors, said it was time for the government to “get on with” legislation to prescribe the objective of super as saving for retirement – and ensure it is not available for any future government policy measures.

“There needs to be a good, national conversation about the purpose of superannuation,” he said.

“We need to have it written in the law what it is for and, in particular, that the savings are preserved until people retire.”

His comments reflect a growing concern in the superannuation sector that it could be used for further political purposes.

They follow similar calls from former treasurer Wayne Swan, now the chairman of the $65bn construction industry fund Cbus.

While the idea of legislating the purpose of superannuation was first suggested by former Commonwealth Bank chief executive David Murray as part of his review of the financial system, which reported in 2014, disagreement over wording saw it lapse when it was presented to parliament in 2016.

But moves in 2020 to allow two drawdowns of superannuation for people in financial need during the Covid-19 pandemic and Scott Morrison’s pre-election policy that super could be used for first-home purchases have reignited fears that future governments could draw on the superannuation pot for a range of crises and policy reasons.

Superannuation Minister Stephen Jones has promised to look at the issue.

Mr Combet said the superannuation system involved a compact that money was saved and preserved for retirement in return for being taxed at just 15 per cent for contributions and earnings in the fund.

“Instead of being taxed at the marginal rate, the money is taxed at 15 per cent on the way in and 15 per cent on its earnings,” he said.

“That’s why you shouldn’t bust it open. No one ever said people should be given a tax concession to save for their first home.

“Pretty soon it will be to pay your private health insurance and then to pay off your HECS debt and your Woolworths bill. That’s not what the tax concession is for. It is to save for retirement.”

Mr Combet said there was a need to educate a new generation of workers, who had not lived through the long policy battle to implement the compulsory super system, on the value of the system.

“We’ve now got a retirement savings system approaching $3.5 trillion which has been built up over 30 years,” he said.

“It outstrips the size of nominal GDP, it far outstrips the market capitalisation of the ASX, it has transformed the Australian capital markets, and has generated a huge turnaround in the current account. We repatriate dividends and interest from investments overseas straight into people’s retirement savings accounts.”

Mr Combet said the industry super movement was considering a campaign to remind people of the value of the current system.

“Seventy per cent of the workforce have come into the workforce since superannuation started,” he said. “They weren’t there at the time when it was being built. There is less awareness of the fact that it was a fight to get universal compulsory superannuation into place.

“There’s a job to go to explain it to the community and why it is so important for them and their future when they retire.”

Mr Combet said it was disappointing that superannuation had become a partisan issue.

“The Liberals seem to hate it and always try to pull it apart. It is an achievement of which Labor is proud,” he said. “The Liberals spend the whole time when they are in government trying to undermine the industry funds in particular and help their friends in the profit-making sector, which is extremely unfortunate.”

Over 30 years the system has seen the rise of a new generation of major financial players such as the $260bn AustralianSuper and the newly merged $230bn Australian Retirement Trust – both now big investors in Australian infrastructure and capital markets.

The three decades have seen the decline of long-established life insurance companies such as AMP, the disappearance of old industry giants such as National Mutual and the exit of the big banks from wealth management in the wake of the financial services royal commission.

Supporters of the system point out how it has played a role in capital markets, including helping to provide capital for the banks in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis and during the pandemic.

Industry super executives are now among the first people to get phone calls from brokers and investment bankers for new deals.

The funds have become major players in infrastructure, highlighted by the $24bn takeover of Sydney Airport this year by a consortium of UniSuper, QSuper and AustralianSuper.

Former Australian Council of Trade Unions official Garry Weaven, who founded IFM and is now an adviser to John Wylie’s Tanarra Capital, describes the rise of compulsory superannuation as a “slow revolution which has completely transformed the nation”.

“There has been a massive disruption – there’s no other way to put it,” Mr Weaven said, arguing that the old mutual funds which once dominated the wealth management landscape of Australia “completely lost their way”.

“They completely lost the objective of putting their members first and became subject to all sorts of bad practices and were eventually swept away,” he said.

But he warns that the superannuation funds of today need to heed the warning and ensure they retain a member-first culture as they become larger.

“They need to remember it can happen to them if they lose sight of ensuring that they need to put their members first,” he said.

Mr Weaven said there was a cultural problem with the old life insurance mutuals because they were based on growing by sales commissions and not on getting the best results for their clients.

He argues that this has created a very different cultural base for industry super funds, while it was the sales commission-based practices that brought down many for-profit organisations.

“From day one, we (industry funds) decided that it was a first principle that we wouldn’t pay any sales commissions to intermediaries,” Mr Weaven said.

The industry super approach was initially to get superannuation sold through industrial bargaining and awards.

“It was an efficient way to enrol people at a basic three per cent and not pay any sales commissions,” Mr Weaven said.

“We immediately got scale and we immediately had lower administrative costs because of not paying commissions.”