RBA urged to hold fire on rate cuts

The property market, share prices and household debt have increased pressure on the Reserve Bank to hold interest rate cuts.

Booming share prices, record household debt and a resurgent property market are increasing pressure on the Reserve Bank to hold fire on further interest rate cuts, despite the economy absorbing a hit from the bushfire crisis, which has rocked the agricultural and tourism sectors.

Futures traders are suggesting that RBA governor Philip Lowe will announce a 0.25-percentage-point cut in rates to a record low 0.5 per cent on February 4 after the multi-billion-dollar losses from the bushfire crisis, but senior economists say such a move may undermine confidence.

Former RBA board member and Australian National University professor Warwick McKibbin said the central bank should hold fire, pointing to evidence that near-zero and falling rates were starting to scare people.

“I don’t think they should (cut),” Professor McKibbin said.

“Once rates get to a certain level, the effects start to disappear quickly. There’s a balance between cheaper credit and making people concerned that there is a serious problem. There are much better policies to stimulate growth than cutting rates.”

The sharemarket hit a record high this week after surging by 21 per cent in 2019, a performance professional investors put down to lower rates here and around the world that forced savers into riskier assets such as equities. “Asset prices have been supported by ultra-loose monetary policy and very high debt levels, and high asset prices do make our financial system more fragile,” Nomura Australia chief economist Andrew Ticehurst said.

Property prices boomed over the second half of 2019 thanks to the falling cost of debt and as regulators eased some lending restrictions.

Dwelling values in Sydney and Melbourne shot 10 per cent higher over the second half of 2019, an annualised return approaching 20 per cent.

Experts are predicting further gains to come.

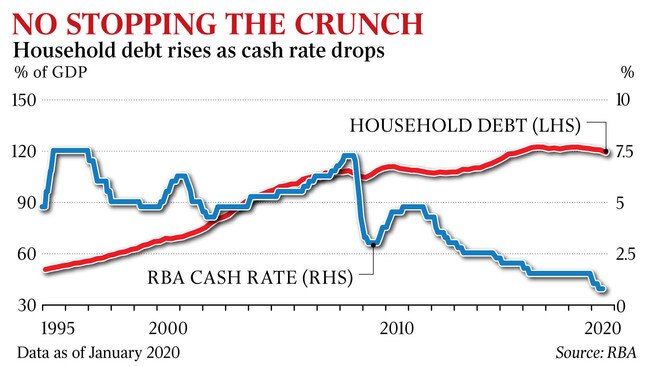

Australia has joined a global debt binge in recent decades, led by households that have borrowed huge amounts to speculate on an epic property price boom.

Data released this week from the Washington-based Institute of International Finance Global revealed world debt smashed records in late 2019.

In Australia, household debt as a proportion of GDP has gone from 50 per cent in the mid-1990s to 120 per cent today. While Australians’ wealth has soared to new highs, the renewed monetary policy easing threatens to push already heavily indebted households to borrow more.

Professor McKibbin said, over time, persistently low rates created “a great deal of problems with the build-up of debt and the distortion of companies’ and households’ balance sheets”.

“Unless the world is suddenly a very different place, eventually you have to pay the costs of excessive debt,” he said.

University of Technology Sydney professor Warren Hogan, a former ANZ chief economist, said cutting again next month would be “insanity”.

“There’s absolutely no need and it won’t do anything. If anything, it will make things worse,” Professor Hogan said.

Liberal MP Jason Falinski, chairman of the parliamentary committee on tax and revenue, said “the case for further loosening is harder and harder to understand”.

Deloitte Access Economics partner Chris Richardson said he “didn’t mind” another RBA cut, but noted that “a recovery in housing prices is good short-term news but it’s bad long-term news, full stop”.

In a note to clients, Deutsche Bank’s global head of thematic research, Jim Reid, said next week’s World Economic Forum in Davos was expected to discuss towering debt levels across the developed world, alongside inequality and the environment.

“With debt piles at record levels and demography suggesting more debt is likely, a world without growth invites a financial crisis of epic proportions,” Mr Reid said. “If we can’t grow our way out of the increasing debt burden, our economic system is very vulnerable.”

Professor Hogan said Australia had spent the past year “worrying about trade tensions and geopolitical risks and they won’t go away”.

“But the main endogenous threat to the global and Australian economy is debt,” he said.

Professor Hogan called on the RBA board, which is chaired by Dr Lowe but is populated by leading corporate and public figures outside the bank, to take more responsibility for guiding the central bank away from decisions based on narrow economic criteria, such as achieving the inflation mandate.

“The board has to take a greater role: who is going to take a broader socio-economic view?

“I think we are right on the borderline of generating significant long-term costs for unapparent short-term gains.”

Mr Falinski said policy and legislative adjustments elsewhere would do more to provide stimulus than monetary easing.

He said responsible lending laws imposed in the wake of the banking royal commission had severely restricted the ability of small businesses to get credit, blunting the pass-through of monetary policy to an important engine of economic growth and employment.

“A more useful thing for creating economic activity would be reform of planning laws rather than monetary policy loosening,” Mr Falinski said.

Professor McKibbin said a bipartisan approach to energy and climate policy would help stimulate investment in new businesses and technologies.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout