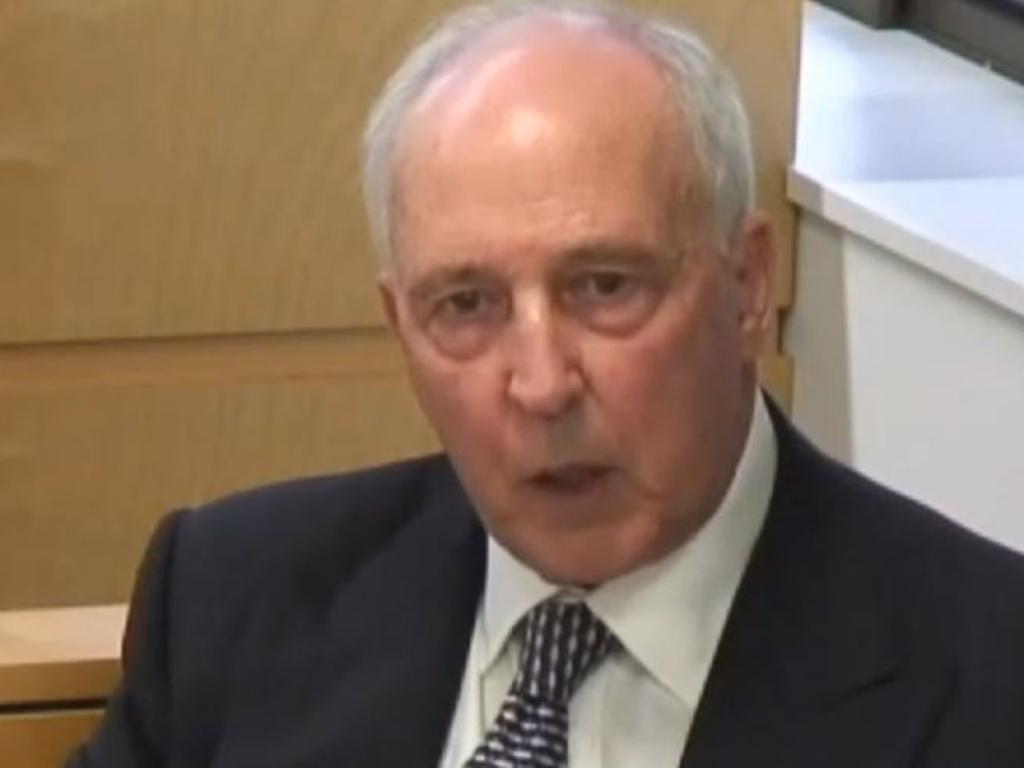

Paul Keating stuck in the 90s with his RBA hang-ups

Paul Keating has never been one to do things by halves. He’s not satisfied with having just a chip on his shoulder; he has two.

One of them is named Bob, the other is named Bernie.

That’s Bob Johnston, the governor of the Reserve Bank he inherited as treasurer from the departing Fraser-Howard government in 1983.

And Bernie Fraser, who he selected first to be his Treasury head and then in 1989 he sent to Sydney to succeed Johnston as the first — and, so far, only — governor from outside the RBA.

He blames Johnston for causing the “recession we had to have” and thereby but for John Hewson and his infamous cake would have cut his tenure as the nation’s first and only Napoleon-grade leader to barely 15 months.

He blames Fraser for “sealing the deal”, so to speak, by costing him the 1996 election and thereby succeeding in depriving the nation of that one great, Great Leader.

It was an outcome made so much worse by the fact that he was succeeded by “Little Johnnie Howard”, who he despised more than any other of his contemporaries; and who went on to get the 11-plus years in The Lodge denied him and the nation.

Indeed, he made all this all but explicit in his infamous statement during the week, lambasting the RBA in both its current and in all its past iterations.

As treasurer he’d “worn the cost of the bank’s indolence in the task of smashing inflation”. That it had been too slow in raising rates in the late 1980s and then too slow in cutting them — so thereby mandating a “recession deeper than Australia would have otherwise had”.

So, what is he telling us, that it wasn’t the recession we had to have? That it was the fault of Bob not Paul?

But how does that sit with his explicit claim, in public, in early 1989 — precisely when the RBA was hiking rates — that “they do what I say”?

As prime minister, he further claimed, he’d worn the “great political cost” of the bank’s rate rises in 1994. So again, it was then all Bernie’s fault not Paul’s.

But, again, how does that sit with his boast to a private dinner in December 1990 that he had the RBA governor — by then, Bernie — “in his pocket”: comments that were explicitly noted; and rejected; and generously excused by the same said Bernie in his departure speech as governor in 1996?

Fraser was not in his pocket — and it was explicitly Fraser not Keating who got it precisely right in raising rates in 1994.

As this paper’s Paul Kelly revealed in his The March of Patriots, Keating forced Fraser to reduce the RBA’s planned 1 per cent rate hike in August 1994 to 0.75 per cent. He would have preferred to “reduce” it away entirely, but Fraser and the then Treasury secretary, Ted Evans, held firm.

As Fraser’s statement on the rate rise phrased it at the time, it followed “deliberations by the board over several months and consultations with the government (my emphasis)”.

And who said central bankers couldn’t do subtle and droll?

Fraser and the broader deeper RBA was precisely, presciently and pre-emptively right; he followed, he had to follow, with further rises in both October and December of the full 1 percenters that had so irked Keating.

Fraser’s October statement referred to “consultations with the treasurer (my emphasis)”; his December one made no reference to consultations with anyone.

Interestingly, that “no consultations” December statement referred inquiries to a “G.R. Stevens”.

More recently known as Glenn, governor Stevens etched his place in political history, earning similar accolades of animus but from the other side of politics, by delivering the first ever rate rise in an election campaign in 2007.

When Fraser moved to hike in August 1994, inflation was about to print at a benign 1.9 per cent for the year to that September quarter.

But his focus was on pre-emption — as the RBA’s has been consistently since, whether of accelerating inflation or slowdown. By June 1995 inflation was up to 4.5 per cent and it peaked at 5.1 per cent at December 1995.

Rather than being “late to the party”, as Keating claimed, Fraser’s RBA was pre-emptively, correctly, early in 1994.

Far more importantly, those 1994 rate rises cemented and indeed created the RBA’s globally pervasive reputation as a fully independent — from political control or even persuasion — central bank, around the 2-3 per cent inflation target which was itself a creation of Fraser.

This has been a combination that has delivered real and very significant value to Australia.

The contemporary heft of Keating’s extended bleat was the RBA’s alleged failure to move aggressively to QE, or quantitative easing, by buying the bonds issued to fund the exploding budget deficit.

As our economics editor Adam Creighton pointed out, at least Keating has put his time in his basement to (good or bad) use by imbibing — indeed, swallowing whole — MMT or Modern Monetary Theory.

But in doing so he has missed, or utterly failed to understand, what the RBA has done this year, in playing its optimum role in responding to the government-mandated recession.

The government ordered the economy into recession; the government — actually, governments — have to order the economy out of recession.

RBA monetary policy/QE can’t do it; even fiscal policy can’t: unless and until businesses are allowed to operate; people are allowed to be employed.

The RBA has put a critically important foundation of stability under the economy and the financial system around a pervasive 0.25 per cent interest rate: that’s the (formal) cash rate; the rate at which it is printing money for the banks; the rate at which it is printing money for the government.

All of this is far more effective than the simplistic QE of other central banks and of MMT.

This is real time 2020 reality; Keating is still living, in more ways than one, in 1994.

Paul Keating has never been one to do things by halves. He’s not satisfied with having just a chip on his shoulder; he has two.