New economics not just about the virus

Whether her landmark speech is now followed by an international agreement like the one in 1944 is another matter, but the two bodies that were created at the Bretton Woods conference, the IMF and World Bank, have given the green light to uncapped government spending and borrowing without later austerity.

Specifically, the World Bank’s influential chief economist, Carmen Reinhart, who literally wrote the book on austerity and was a leading proponent of it after the GFC, told the Financial Times in an interview a fortnight ago: “First you worry about fighting the war, then you figure out how to pay for it.”

The head of fiscal policy at the IMF, Vitor Gaspar, said last week that countries that are able to borrow will be able to keep borrowing, and will not have to raise taxes or cut public spending.

All of which is a full U-turn from what the IMF and World Bank were preaching a decade ago, culminating with the 2010 G20 declaration at Toronto, which highlighted “the importance of sustainable public finances”, and the “need to accelerate the pace of consolidation”, which many countries tried to do, disastrously.

But while a return to budget surpluses and debt reduction was vaguely credible in 2010 it is not now. This year world governments have committed to $US11.7 trillion ($A16.5 trillion) in fiscal stimulus and public debt is about to reach 100 per cent of global GDP, or close to $US100 trillion.

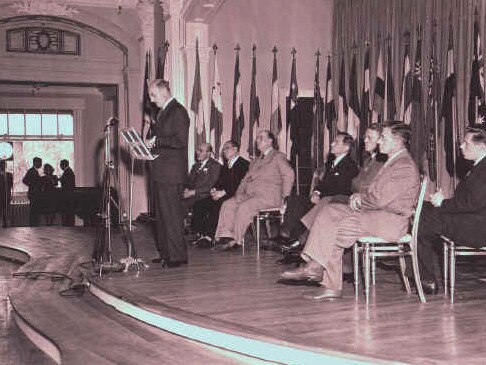

When 44 world leaders met at the Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire in July 1944 to negotiate a new international financial system, global debt was 120 per cent of GDP after the war.

Five years later, it was down to 40 per cent, and by 1971, when President Richard Nixon brought the Bretton Woods era to a close by taking the United States off the gold standard, it was 25 per cent.

But the debt wasn’t repaid with budget surpluses. Rather, global GDP boomed because of post-war reconstruction and a burst of population growth due to the baby boom, so the debt shrank as a percentage of it.

Neither of those things will happen this time. Infrastructure does not have to be rebuilt. In fact there is now a global surplus of it because of the social distancing demanded by the pandemic, and the collapse in both the birthrate and immigration mean that most countries will suffer declining population.

So while the IMF is projecting a rebound in growth from the 4.9 per cent contraction expected this year, it will remain 6.5 percentage points below previous forecasts and require continued fiscal and monetary support to keep growing at all.

The ideas of Modern Monetary Theory and the intertwining of monetary and fiscal policies are now firmly entrenched, despite the pro-forma denials in Australia and elsewhere among classical economists and conservative politicians.

“I don’t subscribe to MMT,” Treasurer Josh Frydenberg said last week. It would blur the independence of the Reserve Bank, he said, and inevitably lead to inflation.

Yes, well, the independent Reserve Bank has already bought 25 per cent of the debt that the federal government has issued this year, and now owns $130 billion worth of it, and is expected to announce a significant increase in its quantitative easing, or bond buying, next month.

In New Zealand, where the Labour government has been returned in a landslide, the central bank has bought 80 per cent of the debt issued by the government this year, so no obvious political cost. In Japan it’s 75 per cent, Europe 70 per cent and in the United States 55 per cent...so far.

As for inflation – it was dead before the pandemic, because of technology.

The digital economy is massively deflationary and had resulted in central banks everywhere spinning their wheels – cutting rates to zero and printing money - as they tried to get inflation up to their 2 per cent targets. The pandemic has rendered them helpless, able only to support fiscal policy by buying government debt with new money.

What would a new “Bretton Woods moment” look like? Perhaps a paper issued on October 9 by the Bank of International Settlements and seven central banks, including the ECB, Bank of England and Federal Reserve (but not the RBA), provides a clue.

It was headed: “Central bank digital currencies: foundational principles and core features,” and explored the creation of a “general purpose” central bank digital currency, which could “provide a complementary central bank money to the public, supporting a more resilient and diverse domestic payment system.”

It might just be an attempt to head off Bitcoin becoming a parallel global currency outside the official system, but it’s hard to imagine what else world leaders would talk about if they gathered at the Mount Washington Hotel again, apart from solemnly agreeing that deficits don’t matter and that everyone needs to do whatever it takes.

The original Bretton Woods essentially made the US dollar the single global currency, with everyone else’s currency pegged to it. That set up gradually, and then suddenly, failed because every country had different fiscal policies and couldn’t sustain a fixed exchange rate (we bailed out quite late, in 1983).

JM Keynes first proposed a global currency in 1940, called the Bancor coin, and the IMF tried it again with special drawing rights (SDRs) in 1969. This time around it’s driven by technology.

That digital technology is a dissolver of sovereign borders as well as deflationary gets expression in many other things, including cryptocurrencies, which have not fallen in a heap as expected.

In fact Bitcoin is back above $US11,000 apiece – simply because it’s scarce, unlike the dollars being conjured up by central bank sorcerers.

* Alan Kohler is Editor in Chief of Eureka Report

When the head of the IMF, Kristalina Georgieva, called for a new “Bretton Woods moment” last week, it completed a dramatic transformation of economic orthodoxy.