Federal budget 2020: Decade of deficits and it doesn’t end there

Treasury is now forecasting at least a decade of deficits, with the underlying cash deficit assumed to be about $53bn in 10 years’ time.

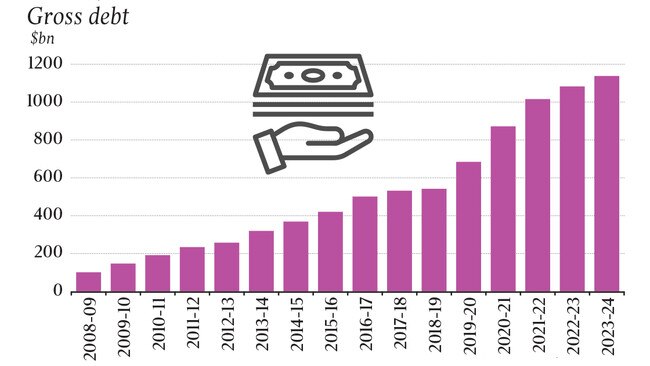

Government debt will keep rising, skipping past the new limit of $1.2 trillion to be $1.8 trillion in 2030-31, or 55 per cent of GDP. Treasury’s long-term forecasts don’t go beyond that year, but there’s unlikely to be a return to surplus in 2031-32, even if the Coalition is still in power, so there’ll be more debt to add to the total after that. That’s hardly surprising: deficits continued for 10 years after the GFC.

The only question will be how much of the debt will end up being owned by the Reserve Bank, something we didn’t learn anything about on Tuesday because the RBA decided to hold off announcing its expected big quantitative easing, or government debt buying, program, presumably until next month.

By 2030, central banks owning lots of government debt will be old hat, in fact in many countries they might have been directly funding government spending, instead of waiting for the bonds to be laundered through private ownership first, as the RBA insists on doing. The fact Australian deficits and rising debt will keep going for at least a decade is partly a consequence of what may be the most shocking thing in a pretty shocking budget: that the impact of on receipts of “parameter and other variations” — that is things outside the government’s control — gets worse each year of the new forward estimates, versus last year’s now redundant estimates, not better.

From minus $41bn this year, to $54.5bn next year, $61.3bn in 2022-23 and finally $76bn in 2023-24. There’s no catch up. Total four-year decline in receipts compared to what they thought before the pandemic: $232.8bn.

That represents about half of the total $480bn deterioration of the budget over the forward estimates, the other half being decisions to offset COVID-19, 70 per cent of which is in the current year.

Apart from the 10-year deficit forecast, the fact that the impact of the pandemic on government receipts keeps getting worse during the forward estimates is the main new thing that was revealed on Tuesday, all the good measures having been dribbled out over the past two weeks.

It happens for several reasons. First, because tax losses incurred this year reduce company tax payments for years to come. Last year, Treasury was forecasting 4.75 per cent growth in corporate gross operating surplus in 2021-22; now it’s predicting a decline of 8.5 per cent in that year.

That doesn’t mean actual profits will fall that much, just that taxable profits will fall because of the carrying forward of this year’s tax losses.

Second, wages growth will naturally fall well short of previous forecasts, but there is also a kind of reverse fiscal drag at work: as individual incomes fall through tax brackets it has a disproportionate effect on tax collections, the opposite of what happens when incomes are rising.

The third reason receipts keep getting worse is population growth. Treasury says it will now slow to its lowest rate in over 100 years, falling from 1.2 per cent last financial year to 0.2 per cent this year and 0.4 per cent in 2021-22.

Treasury now expects net overseas migration to fall from around 154,000 last year to around minus 72,000 in 2020-21, and then to minus 22,000 in 2021-22.

“The fiscal impact of COVID-19 will persist across the medium term. Lower population growth from lower net overseas migration during the COVID-19 pandemic will continue to weigh on the economy. Australia’s economy will be persistently smaller as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, relative to previous forecasts.

“While growth is expected to recover strongly as restrictions are eased, this will come from a smaller base. By the end of the forward estimates, the level of nominal GDP is expected to be around 7 per cent lower compared with the 2019-20 MYEFO, with this gap gradually widening to around 8 per cent by the end of the medium term.”

Just let that sink in: the gap between what Treasury thought last December that the economy would do over the next 10 years, and what it thinks now, is going to keep widening; it doesn’t shrink.

As a result, the new debt limit of $1.2 trillion will have to be raised again — on Treasury’s own forecasts.

The government doesn’t make detailed forecasts beyond “the forward estimates” of four years, but it does make rough medium-term forecasts out to 2030-31, and in that year the deficit is still expected to be 1.6 per cent of GDP.

GDP is forecast to be $3.3 trillion in 10 years, so that implies a deficit of $52.8bn Treasury is forecasting government debt to be 55 per cent of GDP then, or $1.8 trillion — $600bn beyond the new limit.

Does it matter? Not anymore. It isn’t just fiscal policy that’s been recalibrated, but the foundations of conservative fiscal thought.