But despite signing the RCEP deal at the weekend with 14 countries including China, and a passing comment by Josh Frydenberg at The Australian’s Strategic Forum on Wednesday that the government was keen to re-engage in a “respectful and beneficial” dialogue with China, relations with China, including critical trade relations, are set to get worse before they get better.

The government has worked hard to present a public face that it can maintain its current policies and comments about China while the Australian economy can still enjoy the benefits of robust trade with the world’s second-largest and fastest-growing economy.

But that rosy picture is getting harder — if not impossible — to paint given the raft of trade measures being imposed by China on Australian exports alongside the increasingly angry rhetoric from China — from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, to the official China Daily and populist Global Times.

While the Treasurer’s comments to the forum were described as an attempt by the government to respond to business concerns about the fallout from deteriorating ties with Beijing, China is showing no sign of letting up its fury with Australia.

Just in case anyone might be fooled by the weekend press about the potential for the new RCEP trade agreement to provide a breakthrough in ties between Australia and China, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs delivered another attack on Australian policies on Tuesday night.

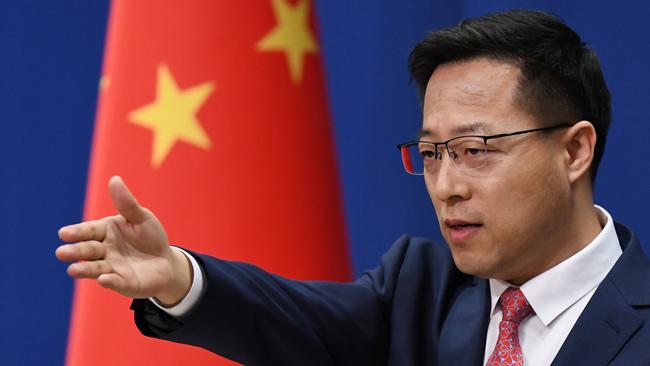

Responding to a question from the Global Times, Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian spelled out China’s list of grievances.

“Australia was the first in banning Chinese companies from participating in its 5G network construction, repeatedly prevented Chinese enterprises from investing in Australia under the guise of ‘national security’, and conducted arbitrary searches of Chinese media reporters in Australia,” he said. “These acts have seriously damaged mutual trust between the two countries, poisoned the atmosphere of bilateral relations and curtailed the original good momentum of practical co-operation between China and Australia.”

China was also unhappy with Australia’s comments on China’s policies regarding Xinjiang, Taiwan and Hong Kong for the “blatant violation of the basic norms of international relations”, which it says have “grossly interfered in China’s internal affairs and seriously hurt the feelings of the Chinese people”.

He also hit out at accusations that Chinese interests had been involved in “intervention and infiltration” activities in Australia, saying there was “no justification for the politicisation and stigmatisation of normal exchanges and co-operation between China and Australia”.

Then there is China’s unhappiness with the way Australia called for an inquiry into the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic in a way that China believed was pointing the blame squarely on it.

Zhao said Australia had “also engaged in political manipulation on the pandemic by promoting the so-called ‘independent international inquiry’, which seriously interfered with international co-operation on pandemic prevention and control”.

While anti-Australian rhetoric is now common from Beijing, the ministry’s most recent list of grievances make it clear that China ties are still in the deep freeze, with more consequences to come.

If China is already clearly pushing back Australian exporters whose business has flourished in response to the China-Australia free-trade agreement that came into force in 2015, it is hardly going to change its mind just because of RCEP or some comments in a ministerial speech.

While Trade Minister Simon Birmingham was unable to visit Shanghai for China’s annual import expo this month, China has watched Scott Morrison’s lightning trip to Japan this week with concern, arguing it is part of a policy of containment against China.

An editorial in Wednesday’s Global Times expressed concerns about the deal signed during the visit, arguing that the closer ties and military co-operation between the US, Japan and Australia were “forcing China to explore deeper military co-operation with others”.

The Times argued that Australia and Japan were acting against their own self-interest by “recklessly taking the first step to conduct deep defence co-operation that targets a third party”.

Countries such as Australia and Japan, it says, were being used as “US tools”.

It warns that “China is unlikely to remain indifferent to US moves aimed at inciting countries to gang up against China in the long run”, adding that it is “inevitable that China will take some sort of countermeasures”.

The editorial was run alongside a photo of the Prime Minister trying a friendly arm bump with Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga, with Suga apparently indifferent to the gesture — implying Suga was taking a cool tone towards Morrison, in contrast to the one of friendship captured on the front pages of the Australian press.

Commentators at The Australian’s Strategic Forum on Wednesday noted Australia’s strained ties with China come at a time when there is a cross party critical view of China in Washington.

While commentators said the style of president-elect Joe Biden was likely to be more smooth and predictable after an erratic Donald Trump, some argued a Biden presidency could end up taking a harder stance against China given its views on human rights in Xinjiang, Hong Kong and Taiwan.

In short, the relationship with China, including the trade relationship, is set to get rockier.

It now appears that China is in no mood to do the government any favours and will have no compunction to use trade ties to express its views. But it will pick moves carefully so as not to be seen to violate any WTO rules.

How much this will damage the economy is yet to be seen as exporters will seek other markets even if they are not as lucrative as China.

The one commodity that appears immune in the short run is iron ore, needed to fuel China’s growth. But as one Chinese source told The Australian recently, Beijing sees Canberra’s revenues from iron ore exports funding an increasing defence budget aimed at containing China.

You can’t blame the Morrison government for wanting to put the best spin on the potential for a new trade deal, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, to provide a possible circuit-breaker in ties with China.