Dealing with fallout from the recession we had to enact

A lot of analysis of the March quarter national accounts, including by the government, seems to be based on the idea that we’re in a normal, cyclical recession. We’re not.

It’s true there will be two consecutive quarters of negative GDP, so it’s technically a recession, but it’s not normal and it’s not the cycle.

Even calling it a recession at all is false: more precisely, it’s the closure of parts of the economy by the government for health reasons, with partial compensation.

You might think it doesn’t matter what you call it, that it’s just semantics and, anyway, it had to happen.

It’s true that it had to happen, but the naming is important: governments are acting like they are gallantly mopping up with Keynesian fiscal policy after a private sector recession that came out of the blue. But that simply isn’t what happened.

The federal government began shutting down Australia’s tourism industry on February 1, when it banned the entry of people from China, but that was not accompanied by any financial help for the businesses or workers affected.

It took 41 days for the first, inadequate, fiscal package of $17.6bn to be put together and announced, and it was general stimulus, with nothing specific for tourism.

Just let that sink in: the government closed an entire industry and then waited six weeks to help those affected by that decision, and when it came, the assistance was untargeted and miserly.

Another example is the university sector, now laying people off because of the disappearance of foreign students, and restaurants of course, and sport — all closures by government decree followed by late, untargeted, partial compensation.

This is the reason Australia is having what Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe called the biggest economic contraction since the 1930s: the government decided to reduce national output and make a lot of people unemployed and then left many of those affected to their own devices.

It’s not just the federal government. All Australian governments have made a series of decisions over the past four months that have destroyed thousands of businesses and put more than a million people out of work, and none of them have properly compensated all of the afflicted.

Targeted support

In fact, targeted support for those affected by the business closures should have been announced simultaneously with the closures and it should have been unlimited.

It is a disgrace that this wasn’t done, that so many lives have been devastated while others have sailed on unaffected because their employer doesn’t happen to rely on travel or crowds mingling together to make money.

In fact, there may well be a wave of class actions as a result, along the lines of the $600m one that is under way in response to the closure of the beef industry by the Gillard government in 2011. The issues are similar this time, only much, much bigger.

It isn’t a question of whether governments overreacted to the pandemic — that doesn’t matter.

Actually, in my view they did the right thing, and the numbers speak for themselves: 7221 cases and 102 deaths. For the US, multiply those numbers by a thousand, even though our population is only a 13th of the US’s. Was that because of the lockdowns, or the fact that Australia is an island? Probably a bit of both.

The problem — the only problem — is that having decided to make people unemployed, reduce incomes and close businesses, they did little to help those affected for weeks, and when the help came, it was untargeted and capped.

The $130bn bazooka was finally produced at the end of March in a blaze of self-praise, but the number has since turned out to be a mistake: sorry, it only needs to be $70bn.

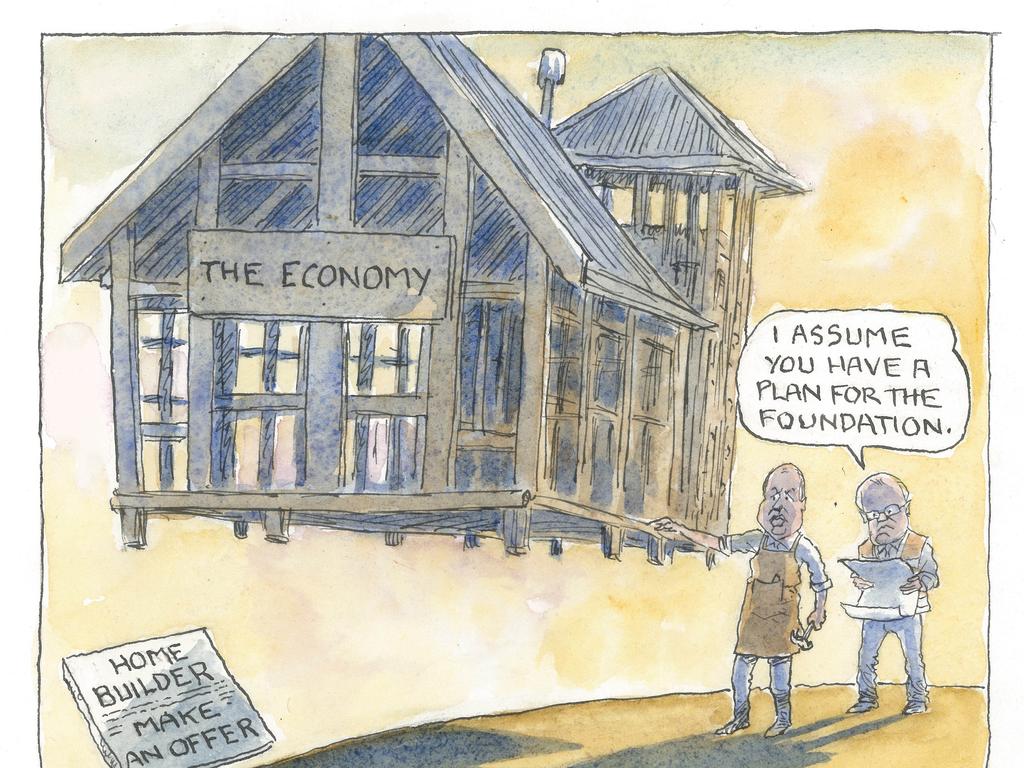

Here’s how Scott Morrison greeted that news: “If you’re building a house and the contractor comes to you and says it’s going to cost you $350,000 and they come back to you several months later and say, well, things have changed and it’s only going to cost you $250,000, well, that is news that you would welcome.

“This is not money that is sitting in the bank somewhere, this $60bn. That is all money that would have otherwise had to be borrowed.”

The analogy is specious: he’s not building something — he’s compensating people for losses caused by government decisions. The number is irrelevant. To protect the economy, and people’s lives, the compensation should be unlimited.

Two questions: first, isn’t it true that the money is borrowed, so putting a limit on the spending is prudent? And second, should the government have to bear all the cost of fighting the pandemic — isn’t it reasonable to shift some of the burden to the community?

State and federal government debt is going to hit record highs, in the trillions of dollars, and won’t be paid back for a generation, if ever. The debt should simply be monetised. A special Act of Parliament should be passed to allow the pandemic debt to be bought by the Reserve Bank and never repaid, as a once-off medical emergency response. It might result in higher inflation, but that would be worth it, and in any case the RBA has been trying to get inflation higher for years.

As for the second question — the government is the community. The way the economic impact of the pandemic has been handled has meant that some have suffered economically more than others.

That’s reasonable if it’s the consequences of their own behaviour, such as borrowing too much money, but this is not like that. If the government had borne the whole cost, then the whole community would share it equally.

Alan Kohler is editor in chief of Eureka Report.

This is not a normal recession — it’s an act of parliament.