Inside Bundaberg farmer-turned banker Lex Greensill’s cult of personality

The cult of Lex Greensill’s personality was one of his greatest assets. But locked away this week in his English home, his empire quickly imploded.

It was a typically pleasant spring evening in September 2018 when I stood next to Alexander “Lex” Greensill in the cabin of a harvester as he carefully piloted the giant machine through towering rows of sugar cane on his family’s farm outside Bundaberg.

When the machine known as the “Colossus” had finished its work, we dined on take-away pizza and mineral water in the dead of night before bush-bashing in his four-wheel-drive past the glowing embers of burning wood piles on land cleared for the next cane harvest.

The next morning we travelled to the highest point on the 5000ha farm, a spot Greensill proudly called the “house block”, where he wants build a homestead for his English doctor wife Vicky and their two boys.

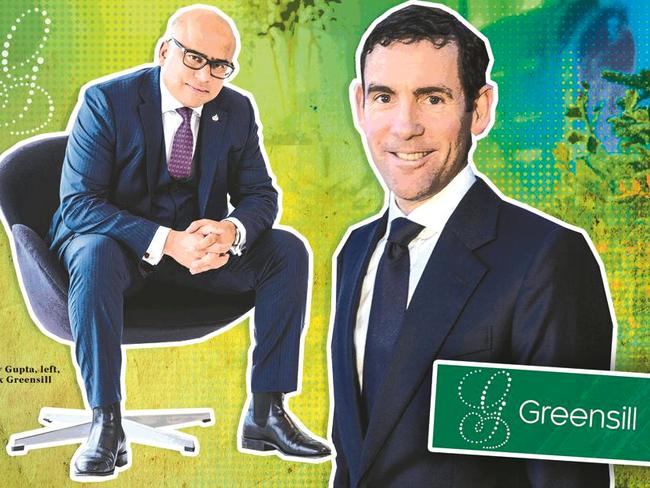

Two and a half years earlier he stood there with British entrepreneur Sanjeev Gupta. As they gazed across the Great Dividing Range in the distance, they made plans to rescue the steel industries of Australia and Britain.

Fast forward to the past week, as Greensill sat marooned in back-to-back Zoom calls in the study of his locked-down northern English property at Saughall in rural Cheshire in a frantic bid to save his company, and that moment with Gupta in Bundaberg has become a poignant one in the life of the 44-year-old entrepreneur.

When Greensill told me in his last media interview in December that “I love a challenge and this year has certainly presented some fun ones to test us out”, it was the ultimate understatement amid the calm before the storm.

“The growth of our business has meant there are some people who don’t have me on their Christmas card list any more. That is the nature of building a disruptive business. Not everyone is going to think I am their favourite person. We take that in our stride,” he said.

Within three months his world would come crashing down. It was the links of Greensill’s supply chain finance firm with Gupta’s GPG Alliance Group that led Germany’s financial regulator the BaFin to this week take the extraordinary step of temporarily closing his Bremen-based Greensill Bank.

It was known as Nord Finance Bank before it was bought by Greensill in 2014, three years after he started his revolutionary supply chain finance firm Greensill Capital.

Those same Gupta links triggered the unravelling of Greensill’s empire on March 1 after its insurers refused to keep covering securities it sells to investment funds, including a string of Credit Suisse Supply Chain Finance funds, which the Swiss banking giant subsequently froze.

Credit Suisse had until then been Greensill’s lifeline. He has strong ties to some key members of its Australian private banking team. although it is understood no Australian private client of the bank is exposed to the frozen supply chain funds.

However, last year, as controversy surrounded Greensill Capital, Credit Suisse reportedly provided an extra $160m to its Australian holding company. Before Monday the bank was willing to stick with Greensill before the insurers forced its hand.

Advisory firm Grant Thornton has also returned to the Greensill fold, now providing it with advice on a restructuring to keep it afloat. The firm was Greensills’ first auditor when he started the company.

While Greensill vowed late last year that COVID had been good to his company, allowing it to grow revenue last year by $400m, the British lockdown hasn’t helped his plight in a time of crisis. In the hours I spent with Greensill in Bundaberg and in subsequent meetings in other places, his charm was unmistakeable.

His laid-back demeanour disguised a laser-sharp mind, but he was also a listener. He asked as many questions as I did and was interested in the answers.

The cult of Greensill’s personality was one of his greatest assets. It took him to the dizzy heights at the peak of global finance. The Financial Times remarked this week how English civil servants were at times “bewitched” by him.

In hours of difficult negotiations with bankers, lawyers and investors over screens in recent weeks, that magic was lost in the technology.

That charm and mastery of networking had previously helped open the most powerful doors in British society. Greensill has advised both Downing Street and the White House on their supply chain finance initiatives and still counts former prime minister David Cameron as a friend and trusted adviser.

Last year the company reportedly held six meetings with the second permanent secretary to the Treasury at Whitehall, before Greensill was accredited as a lender under the British government’s coronavirus large business interruption loan scheme.

It is now folklore that in February 2018 he was awarded a CBE by Prince Charles for services to the British economy.

His billionaire status also bought him the trappings of wealth, even if he publicly despised the tag. “Measuring the value of someone and their contribution to the world by the value of the shares they own seems like an asinine concept to me,’’ he told me back in Bundaberg.

His current home in Cheshire is an early Victorian vicarage. The Greensills completely refurbished the original eight-bedroom building and added a modern three-storey extension with a gourmet kitchen, cinema, games room, cellar and detached offices.

In 2019, Greensill applied to the Saughall and Shotwick Park Parish Council to purchase rural land to establish a wildlife haven.

When Greensill attended The Australian’s annual Global Food Forum in March 2019, he and his staff flew into Sydney from Singapore on one of the company’s fleet of private planes — two Piaggios, a Dassault Falcon and a Gulfstream 650 — which its board decreed last year that it must sell.

Greensill charmed the audience that day with his words, outlining his dream of bringing supply chain finance to the farm gate. His down-to-earth farmer brother Peter, who appeared beside him on stage, struggled at times to keep up. Over coffee after the panel, Lex Greensill was beaming as he privately hinted a big deal was in the works.

Two months later Japanese conglomerate SoftBank’s Vision Fund invested $US800m in Greensill (it added a further $US700m later that year), adding to the $US250m invested by private equity firm General Atlantic in 2018. (The SoftBank investment will now be worth nothing when the rump of Greensill’s operating business is sold to private equity firm Apollo).

In August that year Greensill spent $4.12m on The Glass House, a prime beachfront property on Kelly’s Beach at Bargara near Bundaberg. The five bedroom home spread over three levels — each serviced by an Italian glass Domus lift — sits in more than 2000 sq m of tropical gardens that feature a heated pool, wood-fire pizza oven and barbecue.

The purchase showed his deep passion for his home town, where the Greensill Farming Group was established by his grandfather Roy in 1947 and inherited by his father. He now jointly owns the business with Peter and his other brother Andrew after they bought out their father in 2008.

After the Global Food Forum in March the Greensill jet flew to Brisbane where Greensill addressed the Rural Press Club of Queensland, before travelling on to Bundaberg. The farm and his farmer parents, Lloyd and Judy, have always been his rock. Greensill has also gone out of his way to support the community.

While almost all the sugar cane harvesting equipment used in Australia is imported, in 2017 Greensill Farming chose to support the Bundaberg business Canetec by becoming the initial customer for the local company’s first full-size harvester.

After he moved offshore Greensill travelled to Bundaberg from Britain at least eight times each year, including a one-month stint each autumn, before COVID put paid to those pilgrimages.

His parents were also due to visit Britain last year but postponed the trip indefinitely when COVID-19 struck.

Greensill also tried his charm in Australian political circles.

Last year he pitched his wages-on-demand offering for the Australian public service after hiring former Australian foreign minister Julie Bishop as a senior adviser via her consulting firm Julie Bishop & Partners.

She arranged a meeting for Greensill on the sidelines of the World Economic Forum in Davos with David Cameron and then Australian finance minister Mathias Cormann, where a photo was taken of Bishop throwing snow in the air in the morning sun with Greensill by her side.

Greensill’s grand plans for the local bureaucracy were abandoned when a storm erupted over the behaviour of some of his biggest clients, who were using supply chain finance to bully their smaller suppliers.

Interestingly, Greensill has long been wary of talking on the record about his Gupta links.

In the long interview I did with him over Zoom last December, he was careful with his words on Gupta. He described him as “a valued client” who he was still “delighted to have as a customer”.

“He continues to have our full support and confidence,’’ he said.

Greensill’s answers that day on other issues now look problematic in hindsight, especially on claims that first surfaced last August that the BaFin had been probing his links to Gupta. “No,’’ he replied curtly when I asked if there was any probe. It is understood there was no specific investigation at the time. BaFin officials only appeared in Greensill’s offices last month.

This week the BaFin revealed this week it banned activity at Greensill bank for six weeks after an audit was unable to provide evidence of receivables purchased from GFG Alliance Group.

Greensill then revealed on Wednesday that in late 2020 and early 2021 the BaFin advised that it did not agree with the way those assets were classified by Greensill Bank and directed that they be changed, which they were.

Greensill’s Gupta links and the BaFin probe also played their part in the collapse over the past month of a $US600m pre-IPO capital raising, which was aiming for a $US7bn valuation on Greensill Capital.

European private equity firm TDR Capital reportedly baulked at the issue when it learned that German regulators had concerns about Greensill’s operations.

The collapse of the pre-IPO raising marked the beginning of the end of Greensill’s long-held dream to list a public company in the country of his birth and triggered the current crisis.

Greensill’s claims in that December interview also painted the picture of a company raising capital for growth. It is understood Greensill was then poised to take on a major government client in the Middle East. He vehemently denied it was a post-COVID dash for cash, even if his insurers had told him in September they would not renew his $4.6bn insurance policy, the lifeline for his empire.

He and his executives believed they would eventually come through. With the gift of hindsight and watching the frightening speed at which Greensill Capital has unravelled, it could be described as simply spin when the reality was far different.

History will now be the judge.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout