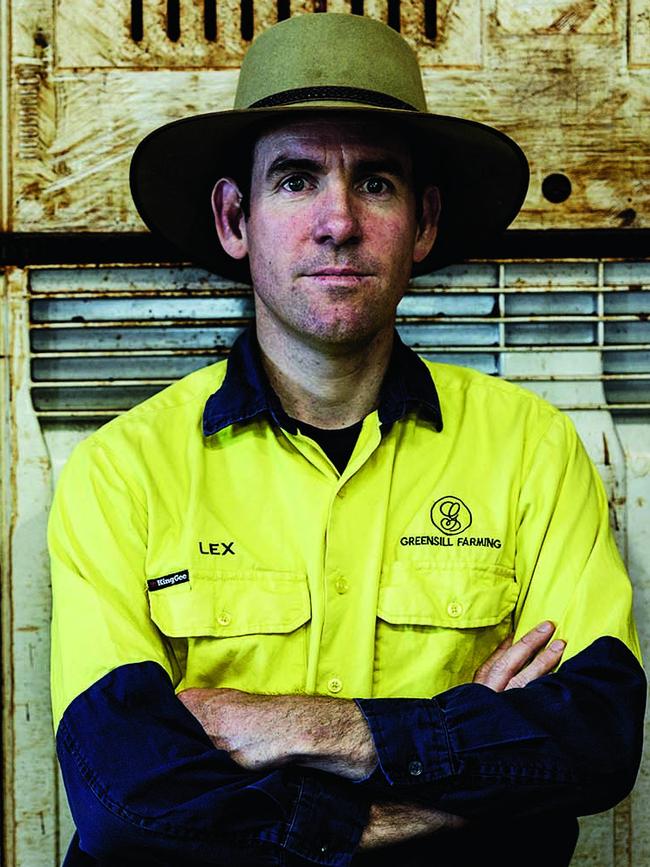

Bundy’s billionaire: Lex Greensill, the cane farmer who owns a bank

Meet the cane farmer’s son whose innovative lending firm is sticking it to the big banks — and making him a motza.

Alexander “Lex” Greensill proudly calls it the “house block”. It is the highest point on his family’s 1500ha sugar cane farm outside Bundaberg, boasting sweeping views towards the Great Dividing Range, across some of the finest farmland in Queensland. One day he hopes to build a homestead here.

But this site has even greater significance for Greensill, his family — and Australian industry. One early summer’s evening in 2016, Greensill stood here with British entrepreneur Sanjeev Gupta. And together, as they gazed over the sugar cane and the orchards in the distance, they made a plan to rescue the nation’s steel industry from the brink. Greensill says that with Gupta, who’d “never invested a dime in Australia”, he talked about how this was a country of such extraordinary opportunity.

Less than a year later, in July 2017, the Gupta Family Group paid $700 million to buy one of Australia’s two remaining steelmakers, Arrium, out of administration. It meant a lifeline for the historic Whyalla steelworks north of Adelaide and the firm’s smaller mills in Sydney and Melbourne, which together produce 70 per cent of the nation’s structural steel. Gupta has since rebadged the Arrium business Liberty OneSteel, borrowing from the name of his UK company Liberty House Group, and spent more than $1 billion doubling the capacity of Whyalla. His vision is to produce “green steel” powered by renewable energy.

In August, Gupta detailed his renewable energy investment plans for the Whyalla region, making a 280-megawatt solar power project the centrepiece of a $US1 billion investment program by his renewables company SIMEC ZEN Energy. SIMEC also wants to build the world’s largest lithium-ion battery in South Australia’s Spencer Gulf region.

What barely rated a mention at the time of the Arrium deal was that it was bankrolled by the London-based “supply chain finance” business Greensill Capital, founded in 2011 by Lex Greensill, son of a long-time Bundaberg farming family.

Greensill Capital is now worth more than $2 billion after receiving a capital injection of more than $300 million from a global private equity giant in July this year. It has become a key player in the disruption of the global financial services sector by using technology to usurp the traditional role played by the big banks. Supply chain finance is a way for big corporations to use cash supplied by third parties — increasingly, “fintech” (financial technology) companies such as Greensill Capital — to pay their suppliers promptly. As a result the suppliers, which are usually small and medium enterprises, or SMEs, get faster access to the money they’re owed, giving them more cash on their balance sheet, while the corporation generally gets more time to pay.

Greensill Capital, which charges a fee and an interest rate for providing the finance, is now the second largest player in global supply chain financing behind US investment bank Citi — and Lex Greensill expects the company to take the top spot over the coming year.

For the 41-year-old, who was this year awardeda CBE for services to the British economy, it’s the fulfilment of what some would have viewed as a crazy global ambition. “Our mantra has been the democratisation of capital,” he says simply. “We use the latest technology to deliver ultra-low cost capital to small companies in every corner of the globe.”

Big dreams indeed, but they came straight from the heart. When he founded Greensill Capital and bought his own German bank to provide new, technology-based capital solutions for business, Greensill was in part responding to watching the financial pressures endured by his family, sugar cane farmers, as they worked to supply large multinationals. His parents often had to wait a year or more to receive payment for their crops from the big food retailers, which used the major banks. “It was that experience of seeing what my mum and dad went through,” he says, “that caused me to say, ‘There’s got to be a better way’.”

It may be one of our most successful hi-tech business exports, but Greensill Capital retains a registered address in a bunch of nondescript offices attached to a sweet potato processing plant in suburban Bundaberg. Lex Greensill says his heart remains firmly in the family business, the Greensill Farming Group, which he owns with his younger brothers Andrew, 40, and Peter, 37.

He has the smarts of an investment banker, wheeling off numbers like clockwork and with the polished presentation to spruik Greensill Capital and its message when required, but he also looks at home driving a sugar cane harvester in the dead of night, or taking his four-wheel drive over challenging terrain in the farthest corners of his property. He has a laid-back demeanour but he’s incredibly sharp. And you can sense he’s a man in a hurry, which is perhaps why he enjoys returning to his roots. “I’m a farmer at heart. And I love it here,” he says, looking out over the rich red dirt of one of the family’s sweet potato farms outside Bundaberg. “Whilst I think I’m blessed to be able to run our financial services company, in my heart I will always be and want to be a farmer.”

The Greensill Farming Group, now run by Peter, was established by Lex’s grandfather Roy in 1947 and inherited by his father, Lloyd. But it was a messy transition. “My grandfather needed the farm to make his income, which meant that we were raised on a shoestring because my dad was a lowly-paid labourer until he was in his 50s,” Lex says. “When his father passed away and then his mother, he inherited the farm.”

Lloyd, who still lives on the family farm in Bundaberg, never planned for his children to stay on the land. In fact he actively discouraged it. Lex graduated from Kepnock State High School before doing a law degree by correspondence, then worked as an articled clerk at a local law firm. Andrew completed an agricultural science degree and Peter went to agricultural college in Queensland.

In 2001, having worked for two years in Sydney at various supply chain finance start-ups during the dot.com boom, 24-year-old Lex left Australia for the UK, where he did an MBA and developed the supply chain finance businesses of global investment banking giants such as Morgan Stanley and Citi. The Bank of England was his first third-party investor. At Citi he also worked on a government-backed scheme to help High Street chemists in London access £800 million of credit on better terms than were available commercially. In 2011, he set up his own fintech focused on supply chain finance, Greensill Capital.

When Sanjeev Gupta bought a bankrupt old steel rolling mill in Wales from a Russian tycoon in 2013, he invited Greensill to tour the site. “He explained to me his vision for British steel and producing green steel,” Greensill says. “Britain produces a lot of scrap steel [that is] exported, melted down and then imported back into the UK. Sanjeev said, ‘That’s crazy. You know we’re losing jobs. We’ve got big value-add industries in the automotive and aerospace [sectors] in Britain. And we have a big infrastructure spend.’ His vision was, ‘Why are we exporting all these jobs?’

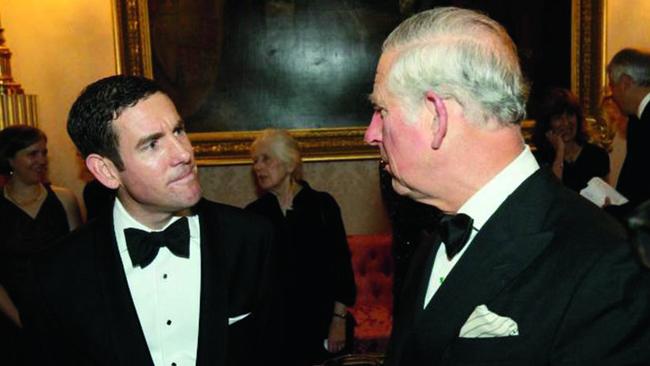

“I bought into that. And if you think about the supply chain that supports, it’s a very exciting thing. The magnification effect of that. So being there when Prince Charles flicked the switch on their electric furnace that had not run for a great many years, and that had been owned by British Steel, was really quite exciting.”

Greensill Capital later financed Gupta’s purchase of Britain’s last aluminium smelter from Rio Tinto in 2016, saving 150 jobs at the site in Lochaber, in the Scottish Highlands. As part of the deal, Gupta bought two hydroelectric power plants. By securitising the cash stream from the hydro plants for 25 years, Greensill was able to provide extra capital to allow Gupta to establish Britain’s first alloy wheels factory at nearby Fort William to supply car makers such as Jaguar Land Rover.

Gupta now describes his vision to produce “green steel” as having the potential to transform the steel industry worldwide. But he says he could not have done it without Greensill. “Like all growing businesses it needs supportive financial partners. Happily our innovative vision for industry and energy was matched by Lex’s innovations on the financial side. His financial solutions are proving to be an important element in the mix turning a dream into an exciting reality for thousands of people worldwide.”

But what Greensill is most proud of is his company’s lending to small and medium enterprises. Over the past seven years, it has facilitated payments to 1.5 million suppliers and provided $US40 billion of financing across 50 countries, the money coming from the Bremen-based Greensill Bank (known as Nord Finance Bank before it was bought by Greensill in 2014) and four finance funds run by international institutional investors.

Small companies, says Greensill, are migrating away from being financed by a term loan from a big bank towards financing themselves through their own working capital. The benefits? “Getting paid straight away. Being able to get your receivables turned into cash straight away to monetise your inventory. It enables companies to respond much more quickly to changes in the economy.

“The loser is the incumbent banks,” he adds. “They were charging between six and nine per cent to provide loans to the people that I now provide loans to at three per cent. They’re having their business models up-ended by us and the people that win are obviously small companies and battlers who are now able to access cash at extremely low rates.”

One of Greensill’s most important global relationships is with mobile phone giant Vodafone, financing its handsets. “We created a disruption that allowed us to buy consumer mobile phone contracts from telcos like Vodafone,” he says. “By tapping much cheaper pools of capital… they could feed through to consumers a much lower cost. We were able to work with Vodafone to deliver the first 36-month contracts for mobile phones in Australia at a very low price point.”

Gold Coast-based Intelligent Infrastructure Solutions (i2S), a supplier for the CIMIC Group’s construction company CPB Contractors, was an early participant in Greensill Capital’s supply finance program. i2S boss Martin Rowland says it “has allowed us to fast-track growth in new markets by opening up working capital. We have employed key people in new regions and have secured new contracts. The program will change the way contracting happens within Australia and allows SMEs to grow and manage cashflow in a way that has never been available in the past.”

At the top end of town, Lex and Peter Greensill became billionaires overnight in July when a strategic $US250 million investment from private equity firm General Atlantic valued Greensill Capital at $US1.64 billion. (Andrew doesn’t have an interest in Greensill Capital.) Bill Ford, CEO of General Atlantic, told The Wall Street Journal: “We’re trying to lever technology to transform the financial services space and in effect fill voids that have been left behind by the large banks. Lex is nothing if not ambitious. We made this investment based on their growth story.”

Greensill Capital now has offices in London, New York, Chicago, Miami, Frankfurt, Johannesburg and Sydney and an exclusive partnership with global tech player Oracle. And it makes money: in 2017 it reported a profit of $US25 million after revenues of $US101 million.

Greensill, now a dual citizen of Australia and the UK, has meanwhile developed close ties at the highest level of British politics and royalty. Having advised both Downing Street and the White House on the successful launch of their supply chain finance initiatives in recent years, he counts former prime minister David Cameron as a good friend. “After I left Citibank in 2011 the British economy obviously continued to be disrupted and David wanted advice,” he says. “The UK government was the first government to implement a supply chain finance program. It was really around: how do we get credit to small companies and what things can we do? And then David introduced me to [then US president] Barack Obama and I did a similar thing for the Obama administration.”

In February this year, Greensill was at Buckingham Palace to receive a CBE. He had met Prince Charles, a patron of the Monteverdi Choir and Orchestra, which Greensill supports, “a number of times before”. “He’s a really interesting and decent man,” says Greensill. “He’s a farmer at heart.”

Back in Queensland, the Greensill brothers have been applying lessons learnt from the difficult experience of their forbears. “Within a year of Dad inheriting the farm [in 2007] we wanted to learn from the errors of the past and we wanted Dad to be able to retire,” says Lex. “So we bought the farm off Dad in 2008. And we’ve been growing it ever since.”

Over the past decade the Greensill Farming operation has expanded to about 2000ha across four farms in the Bundaberg/Isis region. One of its trademarks is a cutting-edge irrigation system that has allowed it to transform disused cattle paddocks into prime agricultural land.

“This farm here is about 1500ha. And we bought it as a cattle paddock,” says Greensill, standing in a field at Stuarts Farm at Wallaville, 40 minutes west of Bundaberg. “In the last 18 months we’ve converted it to a sugar cane farm, which has involved moving millions of cubic metres of rock and earth in order to irrigate in the most energy-efficient way possible. To capture run-off water and to be able to reticulate that. A whole irrigation infrastructure has been built under the ground here.” On the other side of the hill you can see the first crop of sugar cane being planted on the property. When the irrigation work is finished and the crop established, more than $10 million will have been invested in the site, he says. “We have turned this into I would say amongst the finest farmland that there is in Queensland.”

They are also investing in local technology. While almost all the sugar cane harvesting equipment used in Australia is imported, Greensill Farming has chosen to support the Bundaberg business Canetec, last year becoming the initial customer for the local company’s first full-size harvester. “We wanted to keep our money local and give these folks a chance to try and do their business,” says Greensill. He still returns to Bundaberg at least eight times a year, including a one-month stint each autumn when he is joined by his London-based British wife Vicky and their two sons.

With the General Atlantic deal, the Greensills have seemingly fulfilled every entrepreneur’s dream: a big cash injection from a global player. But, far from hitting the jackpot, Lex says they see the company’s valuation as proof of their ability to fulfil their next ambition: to become the biggest supply chain finance firm on the planet.

“It is not about money,” he says. “It is a quest to actually make a difference; the financial outcome of that is a by-product. It is a great privilege to have been able to get where we are today. But the thing that I love is the fact that every day, I get to help small companies who have the same dream that I had. We are actually doing good.”

How does he feel about being described as one of the country’s newest and youngest billionaires? It’s like “talking about someone in third person”, he says. “Measuring the value of someone and their contribution to the world by the value of the shares they own seems like an asinine concept to me.”

As for the Arrium deal, he says he is excited about the future. “Sanjeev had the vision, which I shared, that there was a future for steelmaking in Australia. Not just maintaining what was there, but growing it. An expansion is already taking place across what was the Arrium business, Liberty OneSteel. But it has also flowed through to things like their steel being used in the building of new military ships,” he says of a deal announced in April by BAE Systems to use Liberty OneSteel product to build warships for the Australian Navy.

“We’re really proud to have been a part of supporting that and believing that Australia has an industrial future — not just a services future. That’s something we really buy into.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout