Daniel Grollo’s high-stakes plan to save Grocon empire

The trail of people angry with Daniel Grollo spans three states, but that’s nothing compared to his finances. Can he save his empire?

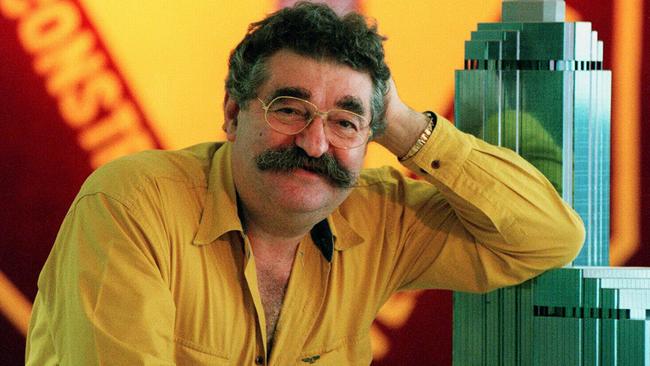

With his arms crossed, sitting under portraits of his forebears in the boardroom at Grocon’s Melbourne headquarters, Daniel Grollo might look like a man under pressure.

But if the third-generation boss of one of Australia’s most storeyed developers and builders feels the weight of history bearing down on him, he isn’t letting on.

He says he has a way out of the financial strife enveloping Grocon after some bad calls in Queensland that plunged the company into the red — and, he wants to make clear, also produced some top-quality office buildings and the “best ever” Commonwealth Games village.

The red ink has Grollo walking the financial highwire: he has personally backed a high-interest loan organised by financier Maxcap that requires Grocon to repay $51 million just seven months from now.

Industry sources speculate the money ultimately comes from Grollo’s father — but he categorically denies this is true.

While Grollo is used to public stoushes with other developers and the construction union, the focus on Grocon’s finances comes at a particularly unwelcome time because the company is about to embark on one of its most ambitious projects, the development of a large chunk of Sydney’s Barangaroo precinct.

Grollo reckons he can fix Grocon’s financial problems by selling a stake in office buildings to be built at the Central Barangaroo precinct to an external investor “in the next six to 12 months”.

“If something unexpected was to happen there are other strategies we could do — we don’t want to elaborate on those because that’s drawing attention to B and C strategies, and we’re not about to do that,” he tells The Weekend Australian.

“We’ve got a very plausible strategy, something we’ve done any number of times.”

The consortium building Central Barangaroo — Grocon, Chinese-backed developer Aqualand and Scentre, which operates Westfield-branded shopping centres in Australia — was announced only last month.

This is despite widespread reports in November that the consortium had won the bid.

The NSW government’s decision in 2015 to add a train station to the project meant bids had to be redone — Grollo insists this does not represent a delay — and the winning consortium has also been fighting billionaire James Packer and developer Lendlease, which is building a vast casino and hotel complex to the south of the site.

At stake are the million-dollar views from the casino through Central Barangaroo and out to Sydney Harbour.

Industry sources say Packer and Lendlease have been “incandescent” over the height of buildings planned for Central Barangaroo.

“I wouldn’t want to get between Jamie Packer and a chunk of money anywhere, but especially not in Sydney,” one source said.

Grollo acknowledges the fight “over the issue of sightlines” but won’t comment.

“I’m not allowed to speak about it,” he says.

He also won’t talk about one of his other big fights, a long-running barney with the militant Construction, Forestry, Mining and Engineering Union.

That’s a new development — for years, Grollo has been the public face of construction industry resistance to the power of the union, a stance he maintained even through costly industrial action and a 2012 blockade of Grocon’s Myer Emporium site in Melbourne.

CFMEU national construction secretary Dave Noonan, who has always maintained the illegal blockade was about worker safety, thinks the episode hurt Grocon.

“I don’t think it won them any friends — well, it won them some politically,” he says.

But he is adamant that Grocon’s current financial woes can’t be pinned on the union.

“We didn’t put him out of business,” he says.

“We don’t have the capacity.

“The only person who’s got the capacity to put Grocon out of business is Daniel himself.”

It wasn’t always like this between the Grollos and the unions.

If anything, they were once a little too close.

In 1983, a magistrate released Grollo’s father, Bruno, his uncle, Rino, and two other property industry figures, Maurice Alter and George Herscu, on good behaviour bonds of $5000 each, with no conviction recorded, after they pleaded guilty to charges of bribing members of the CFMEU’s predecessor, the Builders’ Labourers Federation, in return for industrial peace.

The episode is part of the family’s rich history in a city where the distance between street and penthouse is often not as far as it seems.

Bruno and Rino Grollo inherited the business from their father, Luigi, who started out as a concreter in the 1940s.

By the early 1960s the company had moved on to concreting swimming pools and other large construction projects.

Moving up the construction industry food chain, by 1980 Grocon was a fully fledged developer ready to take on the task of building Melbourne’s then-tallest building, the Rialto on the corner of financial district Collins Street and sin strip King Street.

With the financial support of joint venture partner the Kuwait Investment Authority, the project was a success — although it also sparked a bruising battle with the tax office.

Bruno and Rino Grollo were charged with a $25m tax fraud and the ATO also slapped family company Grofam with a mammoth tax bill.

Grofam settled the case in 1993 by accepting a tax bill of $39m — $19m in primary tax and $20m in penalties.

But the criminal case dragged on for 10 years before spectacularly collapsing in 2000 after the crown’s witness said it was “impossible” for Grocon to have made $26m from building the tower.

Bruno and Rino split their interests after the victory, with Rino keeping the Rialto and Bruno taking on the Grocon name.

Rino, his son Lorenz and their Kuwaiti partners last year finished a redevelopment of the Rialto base that has lured top-tier tenants including Mercedes, which has set up a concept store.

Since 2007 the joint venture has been lobbying former Melbourne lord mayor Robert Doyle — now at the centre of a sexual harassment drama — to shut down nearby clubs because of the “violence and degraded behaviour of the strip”.

The family’s dream of taking control of the whole block moved a step closer in late 2016, when it bought the building housing strip club Showgirls Bar 20, formerly run by John Trimble, the nephew of late crime lord “Aussie” Bob Trimbole.

It needs to buy only one more building — the Inflation nightclub — to own the entire area.

Meanwhile, Daniel’s brother Adam has spent a decade in the headlines for the wrong reasons.

In 2007 Adam’s former wife, Daniela Bussolaro, accused him of hitting her while she was pregnant — claims he strongly denied.

And Adam’s former girlfriend, Ruth Jackman, was in 2014 subpoenaed by the ATO to give evidence about her time working for financier Tom Karas, who police have told the Victorian Supreme Court laundered money for drug kingpin Horty Mokbel. There is no suggestion she has done anything wrong.

At Grocon itself, the low point of the past few years was the 2013 collapse of a wall at its CUB site in Melbourne, killing three people.

Back in the boardroom, Daniel Grollo is excited about the future.

In addition to Barangaroo there is Sydney project Ribbon, a $700m hotel development at Darling Harbour he thinks “will be a really iconic legacy for the skyline of Sydney” because of its unusual shape. “That’s going to be a fabulous project and you know it’s happening, it’s at level 12 in the lift core and moving along really well,” he says.

And then there is the nascent build-to-rent business, where Grocon plans to build apartment buildings that will “never be owned by a mum and dad, either as an investor or an occupant, it’ll only ever be for rent”.

“There’s a whole social extension to that because it gets into the whole affordability issue,” he says.

“In a lot of examples overseas it has really been used as a catalyst to address affordability issues in housing.”

But to make his vision a reality, Grollo needs to put the company’s woes behind it.

In Queensland, blowouts at a tower in Brisbane’s Queen Street and at the Commonwealth Games village project on the Gold Coast, Parklands, have left behind a trail of angry subcontractors complaining about not getting paid and resulted in the loss of the company’s licence to build in the state.

Grollo says that to the best of his knowledge all subcontractors have now been paid, and isn’t ruling out a return to Queensland if the times are right.

“If we got scared off of the market on a bad project there’s plenty of times in the 60-year journey we would have packed up our bags and gone home,” he says.

The company’s financial statements, filed with the corporate regulator, show revenue has declined from about $481m in 2012-13 to about $319m in 2016-17.

Over the same period the company has moved from a profit of $26m to a loss of about $27.5m.

Noonan, who also sits on the board of industry super fund Cbus, which is one of Australia’s biggest property investors, wonders why Grocon has been making losses in a market that has been good to its listed competitors.

“This is not the time where a property developer should be struggling,” he says. “Because if they’re struggling now, where will they be when interest rates spike and conditions get harder?”

There has also been something of a boardroom exodus at Grocon. Chief executive Carolyn Viney and former Mallesons partner Rowan Kennedy, who was chairman, both left in 2016, and former unionist John Van Camp and former Stockland chief financial officer Hugh Thorburn went last year.

The Grocon board is now just Daniel Grollo and Karyn Baylis, the chief executive of a charity called Jawun that seconds executives from corporate Australia to indigenous organisations.

“We haven’t sought to beef it up because it just hasn’t been a primary focus,” Grollo says.

Instead, the immediate focus is on the Sydney projects.

The unmentionable stoush with Packer aside, Grollo is particularly excited by Barangaroo.

“We think that’s a really important project because that’s a project of international significance, being on the foreshore of Sydney Harbour and being the last big piece that close to town — it’s really unique.

“There’s a lot to get into there — it’s two massive projects.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout