Bitter split behind Simon McKeon exit from AMP

It was the Anzac Day holiday in 2016 when the directors of the AMP gathered in Sydney for an urgent board meeting.

It was the Anzac Day holiday on April 25, 2016 when the directors of AMP gathered in Sydney for an urgent board meeting. It would conclude soon after with the resignation of the chairman, one of the nation’s most lauded businessmen, Simon McKeon.

Outside in Sydney it was 20C with filtered sun as Anzac Day crowds rode the ferries from Circular Quay. Inside it was cold with tension as McKeon outlined his decision to quit after agitation from a group of directors objecting to his management style. In the face of their campaign, McKeon had resolved to walk away rather than lead a divided board.

But this fight was not just about style; there were other forces gathering and the power on this board had swayed against McKeon months before.

The following day, April 26, the board issued a statement to the ASX announcing McKeon would retire following a change in his circumstances. So far as McKeon was concerned, handling a board split was a change in circumstance. But for the rest of his directors the fig leaf enabled them to deny any disharmony. By giving no explanation of any kind as to how they had lost their chairman, AMP’s board smoothed the path for his successor.

But for the media and the corporate community it was among the oddest of departures. Speculation ranged from ill health to, well, who knew? “I am disappointed to leave the board following a change in my circumstances,” McKeon said with extraordinary understatement, leaving a trail with what went unsaid.

After a short search, the beneficiary of McKeon’s departure, Catherine Brenner, was appointed chairman on June 24, 2016 and in her first comments she rejected point blank any suggestion that his leaving had anything to do with divisions on the board. Any such suggestion, she said, “couldn’t be further from the truth”. If there had been anything that required continuous disclosure, “we would have told you”.

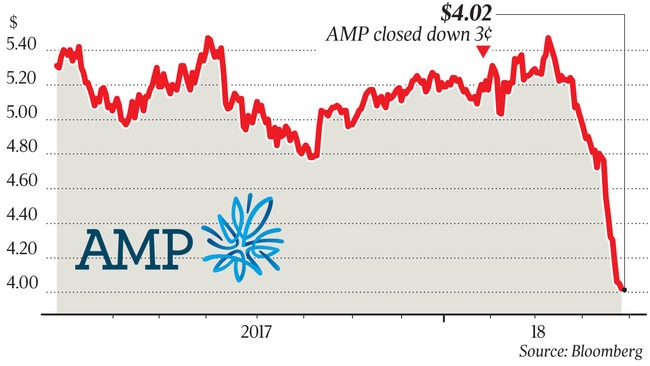

Brenner today could be forgiven for having second thoughts about her ambition to be chairman of AMP. Almost two years to the day of the Anzac Day putsch against McKeon, Brenner is now fighting for her life after the royal commission into banking misconduct heard that criminal charges against AMP were warranted because the company had “deliberately” misled the corporate regulator on a number of occasions — including one where Brenner requested changes to a report on “fees for no service” that was presented to the Australian Securities & Investments Commission as ‘‘independent’’.

The report was personally presented by Brenner and AMP’s general counsel Brian Salter in a meeting last year with ASIC’s former chairman Greg Medcraft and deputy chair Peter Kell.

Salter has stood aside pending an investigation.

The royal commission counsel assisting, Rowena Orr QC, yesterday cited ‘‘governance and cultural practices’’ at the giant insurer in her advice to Royal Commissioner Kenneth Hayne that AMP had breached the Corporations Act. These are cornerstone corporate issues than can ensnare a board and doubtless invite the attention of not just ASIC but also the prudential regulator APRA.

For Brenner, the royal commission inquiry has opened a flood gate into examination of her role as chairman and the performance of AMP in that time. Having tried for two years to fight off the shadow of her day one comments as chairman in 2016 — that the chief executive Craig Meller needed to move ‘‘faster’’ with his strategy — Brenner and the board dispatched Meller abruptly a week ago as soon as the royal commission swung its blowtorch their way.

Brenner has been among the fortunate in the directors’ lounge as a protege of David Gonski, the ANZ chairman and mentor to countless young executives. A legend of both the cloak and dagger and the milk and honey of the corporate scene, Gonski’s word is often sufficient reference for a young player to commence their climb. At the age of 38, in 2008 Brenner was appointed to the blue-chip Coca-Cola Amatil board where Gonski was chair — a signal appointment even for a highly experienced director. She became known as one of the FOGs — Friends of Gonski.

In 2010 Brenner joined the board of AMP. She would come to be known on the board as part of a loose grouping that included Patricia Akopiantz, John Palmer and Peter Shergold.

This was a company that had executed more than its share of chief executives and chairmen over the years, including the cinematic moment in 1999 when then chairman Ian Burgess and four directors fell on their swords to save the board — a distinctive sacrifice that came not long after the removal of the chief executive George Trumbull and only three years before the sacking of the next chief executive Paul Batchelor, followed by the demise of the subsequent chairman Stan Wallis.

This, however, was not the way with Simon McKeon. McKeon had been a highly successful chairman of the fractious CSIRO; he had been a leading sportsman and spent 20 years at Macquarie Group where he became executive chairman of Macquarie’s Melbourne business. He joined the AMP board in 2013 and succeeded Peter Mason as chair in 2014.

In early 2016, McKeon commissioned a “360-Degree” leadership assessment — a classic management tool common to most big companies where external consultants conduct interviews and put together a report of anonymous comments, thus allowing all parties to gain feedback on how they are performing.

McKeon’s interest in the 360-Degree followed conversations he held with directors on a regular basis for two-way feedback. In some of these conversations, director John Palmer had questioned McKeon’s style, the way he operated. The consultant for the 360-Degree was engaged to report back to AMP’s nominations and governance committee, chaired by Brenner, who ran the process.

When the 360-Degree came back it contained some extremely negative comments about McKeon from a minority of directors. Given this was a 360-Degree assessment, the comments were anonymous. One of those close to McKeon at the time said the chairman was startled by the stinging nature of the comments about his leadership style — a style doubtless influenced by the Macquarie way. With Brenner finalising the 360-Degree, McKeon raised questions about whether Brenner should be running the process. He asked her to stand aside in favour of director Peter Shergold to conclude the process. Shergold had no ambition to be chairman and was coming up to the end of his term on the board after eight years. One insider told The Weekend Australian that Brenner had been honest about her ambitions for the chairman’s job when asked.

Shergold took charge on the basis that he had no stake in the outcome of a discussion with the chairman over the comments in the 360-Degree. It would enable him to have conversations with McKeon on behalf of the board. He raised the comments with McKeon saying, “Simon, you do have to think about this.”

As part of the fallout of the 360-Degree, the board became divided along unseen lines. Akopiantz was rumoured to be gathering momentum around Brenner. Shergold opened a deeper conversation with McKeon. But in the vein of these things, none were certain what role others played.

McKeon was understood to have been quickly reaching a decision that with a divided board and some directors moving subtly against him, his future was not going to be spent trying to reunite disparate elements. He did not have a board that saw things his way. It was not something he wanted to continue with. On the holiday Monday of April 25, 2016, McKeon flew in from Melbourne for the denouement. He had made his decision and spoken to Shergold. Two directors could not make the meeting in person and attended by phone — the New Zealand Palmer and the Sydney-based Brenner. According to one director, after McKeon spoke briefly, the meeting was mostly devoted to approving the press release.

The tenor of the boardroom etiquette was clear when one director suggested, “Why don’t we just say you’re too busy?” McKeon was said to be affronted and he articulated a series of points about culture.

Another in a long line of AMP leaders and chairman, McKeon had been knifed, although for once there was no blood. It would be onwards and upwards for everyone. No one wanted to pen another public chapter in the long-running saga of the AMP Hunger Games.

Palmer was appointed chairman on an interim basis while the executive search for a new chairman was under way. Brenner was appointed a month later. She was a confident chair with the right connections and the inner steam for the job. She had been chairing AMP’s life division and now she had the run of her corporate life ahead.

Neither Brennan nor McKeon were available to comment yesterday.

But by the blighted calculus of AMP’s history of destruction from the boardroom down, Brenner now risks becoming yet another casualty as the floor rises up to meet her.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout