Beware tyranny of email says productivity ninja Graham Allcott

Emails follow the modern office worker. They are on our phones, desktop computers and tablets all day every day, weekends included.

Emails follow the modern office worker. They are on our phones, desktop computers and tablets all day every day, from early morning to late at night, weekends included. Studies show the average worker receives 121 emails a day and checks their email 74 times. It is the top form of business communication worldwide.

Last year more than 108.7 billion business emails were sent and received daily, and that is predicted to grow to 139.4 billion by 2018.

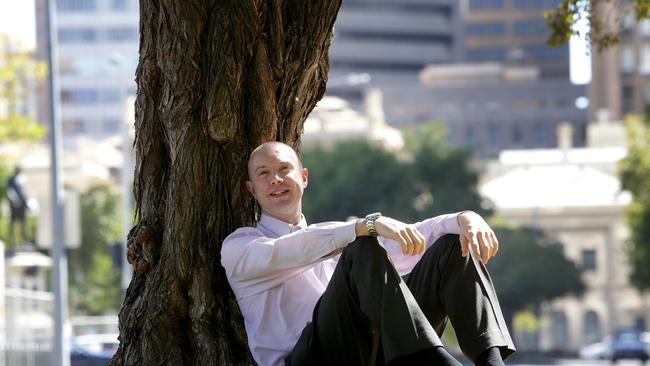

But self-described British-based “productivity ninja” Graham Allcott, founder of Think Productive, says most people feel they need to reply to emails as soon as they arrive, no matter what time, when they may not be as urgent as they believe.

“The million-dollar question is how much time should I spend on email, when should I be on it and when should I not be on it,” Allcott says. “If I’m a PA and I’m the person waiting for the message from the prime minister to say press the button, you need email on.”

But people tend to think they need to reply to emails at all hours of the night or early morning if their manager sends a message, falling into a vicious cycle of unspoken expectations and perceptions of having to be working when you should be switching off.

“What I notice in companies is the cultural expectation, it starts from the bottom up and not the top down,” he says. “Everyone thinks they have to be on email all day because they think their boss needs them to do something.

“If you ever speak to the chief executive they’ll say as long as you get back to someone in a day it’s OK. But what the people at the top don’t realise is if they send one email at nine o’clock at night, people feel they have to respond.”

Allcott says the only way to change the switched-on culture is to have a conversation about expectations and email etiquette.

While many companies have policies on workplace email or social-media use, he says very few have guidelines about responding after hours and when employees should or should not reply.

He says there should be expectations around timeframes for responding to clients, what is acceptable for management contacting staff after hours, and when staff should legitimately be able to ignore emails, switch off or reply.

Having a conversation or a policy about work-related messages will let off the pressure valve, Allcott says, and lead to more relaxed workers who are likelier to return to the office refreshed, ready to focus on daily tasks.

The same applies to setting out of office replies, he says, because they establish guidelines for people who may be trying to get in touch and take the pressure off employees to reply. “These rules exist and there’s no stress, but when it’s unclear and uncertain, that’s where the stress comes from,” he says. “People don’t have policies about ground rules.”

Many of Allcott’s attitudes and ideas about productivity come from his “year of crazy experiments” in 2013.

In each month Allcott trialled a different experiment such as turning off the internet, studying how diet affected productivity or making decisions by throwing a dice.

One month he replied to emails only on Fridays. “Every Thursday it was like Christmas Eve, I’d be thinking what’s going to be on my email,” he says.

“I learned to love email again. I missed a couple of small things but nothing really went wrong.”

Allcott encourages people to have short meetings to start every day, which he says allows him to see how staff are feeling, whether they are up or down, what their daily goals are, and whether they are struggling with anything.

“The most powerful question you can ask is where are you stuck,” he says.

“Spending five minutes on that is better than someone trying to be a superhero.”

Allcott has been in Australia to deliver productivity and information overload workshops, and to open a Think Productive branch in Australia.

Since he began advising on productivity, he has opened branches in the US, The Netherlands and Canada.

Allcott says attitudes to work differ from Europe to Canada to Australia, and what can be important to worksites and companies in one country can be completely different to another.

In The Netherlands and Germany productivity improvements are welcomed openly, he says, because workers are systems and process-oriented.

In Britain the attitude is the opposite, Allcott says, where many people rebel against process-driven systems.

In Canada, Allcott says, workplaces are driven by collaboration and people almost forcing themselves to be superheroes by undertaking every task they are given instead of saying no when overwhelmed.

“What they struggle with is that sometimes you have to be ruthless and you have to be bold and make decisions.”

Allcott says Australians often place a higher importance on work-life balance and flexible hours. While the trend has not taken off in much of Europe or the US, he says Australian businesses value flexibility highly.

“It’s happening with individual companies in other countries but it’s not the culture,” he says.

“Instead they’re trying to make the office fun and keep them there longer and saying this is your life. In the UK and the US it’s much less driven by work-life balance, it’s driven by the cost of office space and hot desking.”

Think Productive in Australia is headed by Matt Cowdroy, who left his career in finance, sales and marketing after reading Allcott’s Productivity Ninja book on a plane.

Cowdroy has a team of three in Sydney and is advising companies on productivity measures through workshops and seminars.

Their work includes the not-for-profit sector.

Advice includes making working life more productive, and takes cues from Allcott’s successes in reshaping daily office life.