Banking royal commission live: insurance hearings - 13 September

Another harrowing day of evidence in the insurance round of royal commission hearings. Here’s what we learned.

- TAL hires a private investigator

- Nursing case study

- ‘Every kind of report’

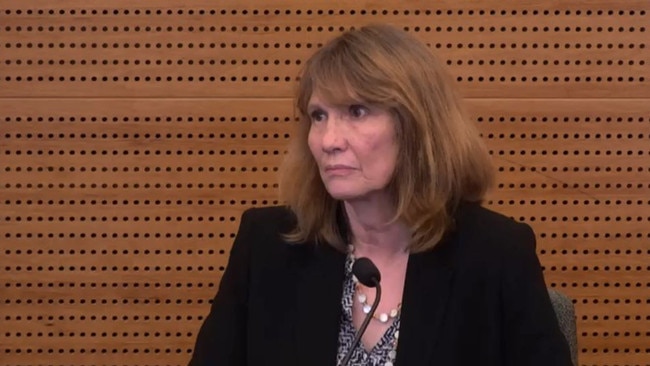

- TAL’s Loraine van Eeden appears

- Industry issues

- An apology, but no review

- More old definitions

- Breast cancer case study

- CommInsure’s dealings with ASIC

- No acknowledgment of wrongdoing

- CBA’s words, ASIC’s media release

- Regulator asking the regulated?

- Problem pamphlet

- Consumers misled

The Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry is conducting its sixth round of hearings, focused on insurance, in Melbourne. Follow the proceedings with us live from 9am each day.

4.30pm: Here’s what happened at the royal commission today

Thanks for joining us for another harrowing day of evidence in the insurance round of hearings at the financial services royal commission. Here’s what we learned:

- Commonwealth Bank knocked back a life insurance claim from a woman who had breast cancer despite the pleadings of doctors and by relying on a two-decades old medical definition that it refused to backdate.

- CommInsure misled customers over information provided in its ads for trauma cover that led people to think any heart attack would be covered. In fact, the product disclosure statement said only severe heart attacks were covered.

- TAL took more than three years to accept a customer’s life insurance claim in full despite pressure from the Financial Ombudsman Service, and also asked the insured to repay a refund of premiums before the company would pay out the claim.

- TAL subjected the same customer to an extensive period of surveillance, both by sending a private investigator to snoop outside her house and by searching her social media presence, in a bid to prove she was well enough that it could stop paying the claim.

- TAL continued to push the client to complete a daily diary of her activities even though one of the symptoms of her mental illness was short-term memory loss, and the diary requirement made her mental condition worse. Eventually the insured completed the daily diary and it contains multiple references to feeling anxious including about TAL and the diary. The diary also makes references to self-harm.

- TAL general manager of claims Loraine van Eeden will be back in the stand at 9.45am tomorrow.

If you or anyone you know needs help: Call Lifeline on 13 11 14

4.15pm: Hearing concludes for the day

The referral of the insured’s case to the claims decision committee suggests the insured’s claim was spurious and the insured always intended to write the book.

The committee agrees that TAL could stop paying benefits based on part of the Insurance Contracts Act that deals with fraudulent claims. This was not a fraudulent claim.

TAL wrote to say the company would not be making any further payments to the insured.

TAL set out an extensive list of the surveillance it had conducted.

“We believe that TAL has been more than reasonable with your Income Protection claim, however due to the evidence available to us we will now look to seek recovery of benefits paid from at least 01/06/2012 if further evidence is located we reserve the right to request the full recovery. Please arrange for recovery of this benefit which totals $68,890.00.”

So this was TAL telling the insured for the first time about the surveillance which would have been a shock to the insured, and TAL saying they wouldn’t pay any more benefits would be a shock, and requesting the repayment of $69,000 in benefits would be the biggest shock of all, Ms van Eeden agrees.

“I was shocked when I saw this,” Ms van Eeden says.

The witness stands down and will return at 9.45am.

4.10pm: ‘Blah, blah, blah’

The case manager emailed UHG’s medical adviser Dr Phang to say “I have had quite a few emails from our lovely client.”

They’ve altered the diary requirement now because of letters from her doctor “stating she cannot do them, blah, blah, blah”.

The doctors need to see the surveillance, TAL suggests.

This is “terrible” Ms van Eeden says now. “We pay over 25,000 claims and I have never sen one handled in this way before.

Dr Phang says that any attempt by TAL to suggest anxiety is other than persisent would be met with significant opinions to the contrary - so perhaps it was worth looking at whether it was still affecting her work ability. That is, the doctor was trying to help TAL avoid the claim.

Psychiatrist Dr Grant opined that the insured could work in a different job and there was nothing medically to suggest completing a diary would exacerbate any anxiety.

So the case manager referred the insured’s situation to the TAL claims decision committee, which is a committee the case manager sits on.

This is something TAL has changed now to ensure impartiality in their decisions.

4.02pm: Hayne ask about motives for misleading FOS

One of the doctors who had seen the insured provided another report saying she was suffering severe anxiety attacks exacerbated by the diary requirement.

The case manager said the insured’s condition was by no means life threatening.

The complaints resolution manager suggested it might be prudent to remove the diary.

In February the case manager decided that the portions of the diary already completed were enough, and TAL decided not to insist the insured continue to provide the diary.

TAL told FOS the diary was standard practice in the industry.

But it wasn’t standard practice, Ms van Eeden accepts.

Commissioner Kenneth Hayne AC QC wonders why TAL told FOS a diary was standard practice in the industry.

The behaviour was inappropriate and not in the interests of the claimant or TAL, Ms van Eeden says.

3.58pm: ‘For me this is absolutely bullying’

On Christmas Day, the insured sent TAL a medical certificate from her regular GP to confirm her medical condition causes confusion and she is unable to fill out a diary of daily activities, and she is getting “quite stressed” doing this.

The case manager told the insured that TAL thought requesting the daily diary was not unreasonable, and she needed to complete the diary so her payments were not delayed.

Ms van Eeden concedes this was a threat to stop or pause benefits if she didn’t write the diary. “For me this is absolutely bullying,” Ms van Eeden says.

The insured went back to FOS about the diary.

The case manager wrote to the insured to say payment of a benefit was subject to proof of entitlement.

The case manager said the diary had to be completed until the end of March 2014, saying TAL was not trying to worsen the insured’s health and was acting in utmost good faith.

TAL asserted the policy - not TAL - was requiring the diary. But it wasn’t a term of the policy. Ms van Eeden agrees the assertion was incorrect and a breach of professional standards.

TAL breached its duty to act with utmost good faith, she says.

The insured completed the daily diary and it contains multiple references to feeling anxious including about TAL and the diary and there are references to self-harm.

Ms van Eeden says this goes to the “inappropriateness” of the way the claim was handled.

Ms Orr: “Are we getting a bit beyond the inappropriate stage now?”

Yes, Ms van Eeden says this is bullying. And agrees the diary requirement was exacerbating her claim and in the face of that medical evidence TAL kept making her do the diary and that resulted in harm to the insured.

If you or anyone you know needs help: Call Lifeline on 13 11 14

3.47pm: ‘I’d love to close this before Xmas’

The case manager asked for an opinion from a psychiatrist.

“I’d love to close this one down before Xmas if it could be pushed through, if not that’s OK too,” the case manager writes.

Ms van Eeden says this is inappropriate.

A colleague asks for a copy of the surveillance DVD so the psychiatrist can draw his own conclusion of her mood.

The insured’s GP wrote to say that the insured presented in an “extremely anxious state” and adding that the requirement for a daily activity diary was exacerbating her state of anxiety.

The case manager emailed the psychiatrist’s colleague to say she would “love” the diary completed but “if I keep firm with my request it would be seen as going against doctor’s advice” and “HELP”.

The psychiatrist suggested the case manager write to the GP and ask him to justify his opinion.

Later that day, the psychiatrist emailed the case manager “A picture of your favourite Claimant” with the line “I thought this would make your day.”

Ms van Eeden says this is not appropriate and agrees it belittled the insured person.

3.37pm: Private investigator bill: $20,000

Ms Orr is unimpressed and turning the screws.

Ms van Eeden concedes the content of the investigator is personal, intrusive, there is commentary about the insured removing her clothes to get in the swimming pool, there is commentary about her behaviour around her partner.

She admits this is not how to treat any claimant, and no policyholder should ever be subjected to this sort of investigative activity.

TAL paid the private investigator about $20,000 to watch the insured, who had income protection payments of $2750 a month, and to try to find a way to stop the payments.

Next, we see that TAL asked the insured to complete a daily activity diary.

But the insured expressed concerns about being able to remember what she had been doing a month ago as one of her symptoms was short term memory loss.

The company told the insured that most TAL claimants had been required to produce a daily diary but this was not true.

The diary was inappropriate for this insured and had been used to try to disprove her entitlement to the claim, Ms van Eeden accepts.

3.31pm: Four-month surveillance campaign begins

A TAL-authorised detailed and sustained surveillance campaign of the insured started and ran for at least four months.

Oops — another document hasn’t been properly redacted. Rowena Orr QC is also annoyed that the person TAL presents is unable to explain so many aspects of the case study.

We’re hearing about a Background Investigation Report. It summaries searches for government licences, news text, white pages, Google searches, ABN searches, searches of social media sites. That is, desktop surveillance.

Ms van Eeden accepts this was part of a broader inappropriate approach towards the insured which was that TAL was seeking to avoid paying the claim.

There was also physical surveillance on and off for four months and the investigator provided photographs and videos — the information was very detailed and often very personal.

TAL’s instructions were to observe the member and the extent of her alleged” psychological condition, complete with a photo of her, a photo of her house, her phone number.

The report comes back — the claimant was observed selling her book, in the company of a male person in a close relationship, bush walking swimming, exercising, attending a takeaway foodstore, with a “happy, confident” demeanour showing “no outward signs of her alleged psychological condition”.

The insured was surveilled for seven days over a two and a half week period, with video on four days.

Sometimes the investigator went up to the house and inspected what was going on.

She was subjected to surveillance from 9am when having breakfast in a cafe until 6pm

3.22pm: TAL hires a private investigator

But wait, there’s more.

Someone at TAL decided to Google the insured and found out she had written a book and done some public speaking events.

They also found out she had lost money on doing this.

A new case manager instructed a private investigator to undertake an investigation of the insured.

Ms van Eeden accepts TAL was looking for a reason to stop paying the claim and there were no safeguards or approval process in TAL governing a case manager undertaking surveillance.

The commission is shown a document but quickly Ms Orr has to take it down. She apologises and says the commission has worked very hard with TAL on the redactions.

Commissioner Kenneth Hayne interjections: “Well the primary responsibility for redactions lies with TAL.”

The document we can’t see asks for a review as the insured says she can’t work but she is a full-time carer, can this be deemed as work? The document asks for a “customer visit not a full factual” with surveillance for three days.

The case manager was trying to support her theory that full time caring work would disqualify the insured from the rest of her benefit, as much as $792,000 if she kept getting paid until age 65.

The instructions to the private investigator are to “complete as many searches as possible” and “conduct a period of three days surveillance”.

“Please complete a Pre text at the hospital and maybe discuss with the local police about her,” the instructions read.

Ms Orr suggests the private investigator was being asked to go to the hospital and under some pretext seek information about the insured.

The case manager’s email reads:

“Hi Mark — OMG here is another one for you. I want results”

Ms van Eeden was “shocked” when she saw this, and admits the case manager wanted the investigator to find information to provide a basis for TAL to cease paying the insured’s claim — a $792,000 liability.

The directions, tone and information in the email were totally unprofessional, Ms van Eeden says.

3.11pm: ‘It should never take so long’

FOS emails to say it’s concerned that TAL is failing to comply with the determination by seeking payment of the premiums upfront.

TAL decided not to press for payment of that amount before assessing the claim.

The case manager asks the insured for updated medical information, and the insured provided medical certificates confirming she was unfit for work.

TAL finally accepted the claim in 2013, just over three years after the insured lodged her claim. Ms van Eeden says this is “inappropriate” and it should never take so long.

The claim was only accepted up to 2012 though and the insured would be paid $89,000 including interest.

When did TAL pay that amount? Ms van Eeden doesn’t know.

Over a month later the claim for the remaining period was accepted — even though FOS was hurrying them up. TAL paid an extra $35,000 but this didn’t include interest.

Then TAL paid interest but not for the whole period and then ultimately TAL paid the interest for the correct period.

Ms van Eeden admits it should not have been such a battle for the insured.

What does this say about TAL’s respect for FOS?

Ms van Eeden says the case “did not serve the client” and the company has made changes to its internal dispute review team, and TAL should have moved quickly to put the insured in the position she would have been in had TAL assessed her claim correctly three years earlier.

3.07pm: Orr makes rare mistake in naming insured

TAL didn’t accept a FOS recommendation in favour of the insured.

There is internal discussion about the ruling. One staffer wrote to express a view that there was nothing to lose by pressing on with the dispute.

Ms van Eeden concedes TAL’s decision to press on placed the insured in a position where she had to battle further over a claim she had made more than two years ago.

The matter went to a FOS determination, which was in favour of the insured and directed TAL to reinstate the policy and pay benefits with interests.

Some individuals in TAL were disappointed with the decision, Ms van Eeden says.

By this point there was a new case manager at TAL for the claim — Ms Pratt.

Ms Pratt told the insured before her claim for benefits could be assessed she needed to pay $2215 in premiums — the amount TAL refunded when it avoided the policy.

This is “very appropriate”, Ms van Eeden admits.

FOS had already told TAL to offset the refunded premiums against the benefits that it paid out.

Ms Orr — in an exceedingly rare mistake — accidentally names the insured, for which she apologises.

Ms Orr has been on her feet talking for almost four days.

3.01pm: FOS request roils TAL

An internal TAL email about the dispute reads: “FOS are clearly going to put us to the sword on this.”

A staffer says TAL won’t have guidelines for everything FOS is asking for.

Ms van Eeden concedes that FOS’s request for TAL’s underwriting guidelines created some internal consternation at TAL.

We’re now more than two years after the insured made her claim.

FOS made a recommendation, saying that in order for TAL to avoid the policy it must be established that the applicant failed to comply with her duty of disclosure.

FOS wasn’t satisfied that the applicant had depression, anxiety and/or stress prior to commencing the policy.

So the applicant hadn’t breached her duty of disclosure, FOS said.

FOS found the insured had 10 days of leave due to stress at work and home but this wasn’t why she reduced her working hours. FOS was not satisfied the applicant knew she was required to disclose stress she had experienced from time to time due to working in a stressful environment and caring for a partner with mental illness.

So the insured didn’t breach her duty of disclosure, FOS recommended.

2.50pm: FOS complaint

The insured complained to FOS.

TAL said the insured made misrepresentations about a medical history of seeing doctors in relation to depression, anxiety and or stress, we hear.

This was the first time TAL had framed the issue as depression or anxiety.

Ms van Eeden doesn’t know where the references to depression and anxiety come from.

Let’s look at some supporting letters from doctors.

One doctor said the insured had never been diagnosed as having depression or anxiety at that time.

Another doctor said the insured was distressed due to an upcoming court case and it was not a mental condition.

Another doctor went further: “Please do not read between the lines for the medical history recorded and make ill informed decisions. A little knowledge is a dangerous thing.” The doctor added the insured had stomach discomfort and there was no correlation to mental illness.

Another doctor says there was no evidence of any pre-existing condition.

TAL didn’t use this information and instead defended the FOS dispute. Ms van Eeden didn’t know why — it isn’t conduct she would have expected from TAL.

A conciliation conference didn’t resolve the dispute.

TAL asked for more information from Medicare.

Could this be a delaying tactic, asks Ms Orr.

Ms van Eeden says either a delaying tactic or TAL wanted more information.

But they didn’t get any new information from Medicare because the insured hadn’t even received Medicare services in the period in question.

TAL asked for more material from the psychiatrist, who refused to release without a subpoena.

There’s a quick confusion about dates because the FOS dispute went on for so long: it took nearly two years.

2.39pm: Pointless resolution

We’re still looking at a letter that TAL sent to the insured, which refers to part of the Insurance Contracts Act.

The act says that an insurer can avoid a contract within three years for an innocent misrepresentation, but under no time limit for a fraudulent misrepresentation.

It wasn’t suggested that the insured had made a fraudulent misrepresentation — but this provision was relied on to avoid the contract.

The insured made a complaint, which triggered internal dispute resolution processes.

The complaints resolution manager says TAL’s previous letter explained why the policies were avoided.

Ms van Eeden admits the internal dispute resolution didn’t seriously engage with the insured’s request for a review, and just repeated the decision of the claims team.

So there wasn’t much point to the internal dispute resolution process for the insured.

Ms van Eeden accepts this file doesn’t reflect the dispute resolution team performing its proper function and this was conduct that fell below community standards.

2.33pm: Policy cancelled

TAL emailed the insured to say her income protection application would have been declined based on a history of work-related stress.

The email said the matter was referred to the legal team to advise on “potential remedies”.

“I’m not very happy,” says Ms van Eeden, looking at the email. She agrees it would cause the insured considerable distress and it looked like TAL was considering pursuing a legal remedy.

The insured asked what TAL meant by her history of work-related stress, as this was news to her.

She had been told the claim would be processed within five working days and that after a number of months the delay was exacerbating her condition.

TAL decided to avoid the policy as it wouldn’t have provided the policy if it had known about the work related stress.

The letter explained the insured had been asked about depression, anxiety, etc, and her response was not accurate.

Ms Orr wants to know why Ms van Eeden is smiling?

We might infer it is incredulity.

“I don’t agree with that,” Ms van Eeden says.

The letter says the insured failed to fully outline her medical history, and TAL was therefore avoiding both policies.

Ms van Eeden says there are a number of errors in the letter: the claimant wasn’t given a chance to provide extra information, it wasn’t appropriate to accuse her of not providing all the information, and the company shouldn’t be cancelling the policy immediately without any additional communication.

2.27pm: Carer’s role

We look at the case manager’s file notes.

The notes say the application was “borderline standard to begin with”.

When the insured made the application, it was viewed as a standard application, but it was on the verge of being viewed as a non-standard application that might have attracted a premium loading, Ms van Eeden agrees.

But this is a factor that should have nothing to do with claims, she concedes.

TAL told the claimant’s insurance consultant about its nondisclosure concerns, saying it appeared the insured may have had consultations in relation to a psychological condition before the policy started.

The case manager wrote to the insured to say there were concerns about what she had disclosed, adding further materials had been requested.

The insured emailed the company to say she had disclosed everything.

The case manager referred the manager for a retrospective underwriting opinion.

The insured continue to maintain she had disclosed everything.

The underwriter said if it had known the extra information, the application would have been declined for work-related stress.

The GP had mentioned six single days when the insured was not coping with work and home stresses but said they were unrelated to her new anxiety condition.

TAL brought in two more reports from psychologists from the insured’s workplace. Only one of those was in the period prior to the claim.

But she was there finding out information about her carer role with her partner and she wasn’t seeking treatment.

Ms Orr: “Now, that couldn’t reasonably have been characterised as workplace stress, could it?”

Ms van Eeden: “No.”

2.18pm: A fishing expedition

Was the general review flag a fishing expedition, Ms Orr asks. One undertaken despite references in the TAL guidelines saying staff shouldn’t go fishing?

Ms van Eeden concedes it was a fishing expedition.

The insured was subject to a general review.

The guidelines say that TAL employees should consider the scale of potential collective claim costs against the cost and time of reviewing disclosures is treated with a “rational” approach. TAL should do a thorough review where the claim amount is large or for a lengthy duration.

Ms van Eeden concedes that a guiding principle in working out whether case managers should do a general review looking for adverse nondisclosure was TAL’s bottom line.

So the insured’s case manager, Ms Holborn, formed the view that the insured may have failed to disclose relevant information.

The case manager had warned of possible medical nondisclosure — the only reports to date indicate possibly three consults in 2007, treatment appears minimal, not initially taking any eds, maybe Workers Comp involvement had delayed the process. The case manager wanted more information. Ms van Eeden concedes that these questions had been resolved by the decision to offer the policy and that there should not have been any investigation of whether the insured can justify the level of cover applied for.

2.10pm: Red flags

Back from lunch and we’re again following the case of an insured person who made a claim with TAL.

Senior counsel assisting the commission Rowena Orr QC is asking questions of insurer TAL’s Loraine van Eeden.

With consent, TAL sought records about the insured, including medical records from her GP and psychiatrist, Medicare history, private health insurance cover and claims history, the treatment file at her workplace, her workers’ compensation claim and her tax records.

Why seek all those details, asks Ms Orr.

Because TAL was trying to understand her medical condition “and also the financials”, Ms van Eeden says.

By at least 2016 it was standard practice in TAL to look for red flags within insurance claims.

We look at the disclosure review guide for claims from September 2016. TAL didn’t have formal guidelines of this sort before then. But it should have, Ms van Eeden concedes.

At the time of claim, the claim information should be reviewed to ensure the customer complied with their duty of disclosure, the document says. If “red flags” are identified, case managers must gather all the relevant details for a complete history.

Insurance “red flags” occur when inconsistencies are identified, and general review flags might include a claim within proximity of the risk commencement date. This means within 12 months, Ms van Eeden says.

This document formalises processes that were already in place.

So if a claim was made within 12 months, the case manager was to check if there was “adverse nondisclosure” ie adverse to the insured because it would provide a basis for TAL to avoid the policy.

1.01pm: High risk claim

In 2010 the insured sent in a claim form with accompanying documents.

She was claiming for stress-induced depression and anxiety. Symptoms began on 30 June 2009. She ceased work on 1 January 2010. Her symptoms started after a meeting with her nurse unit manager. She was first unfit to work on 1 November 2009 but continued to work until she saw her GP in January 2010.

She said she made a workers’ compensation claim and he attached a medical certificate from her GP.

Her GP listed the illness as generalised anxiety disorder; she’d experienced a loss of confidence in both nursing management and her own skills.

The GP attached a letter dealing with the refusal of her workers’ comp claim, saying the insured had been “extremely and uncharacteristically distressed” and this had been something new to her.

The GP said the insured had previously had issues in caring for her partner who had an mental illness but there was never any reference to anxiety or depression.

The GP referred to six single days when the insured was not coping with work stresses, saying these were single day events, and that she was otherwise well.

The insured had initially thought the current condition was an exacerbation of a previous anxiety state, but she reviewed her notes which indicated this was a new onset illness.

TAL classified the claim as “high risk”.

What’s the definition of high risk, Ms Orr asks.

Ms van Eeden says while she’s seen the term, she’s not sure of its actual definition.

Is the term high risk used because TAL takes a harsher stance assessing cases where stress or depression is related to work stress, asks Ms Orr.

Ms van Eeden thinks it’s just the sensitivity when stress is involved.

Ms Orr suggests that might a good time for a break and Commissioner Hayne agrees.

12.52pm: Nursing case study

We move on to claims where TAL has avoided a contract or refused to pay out because of nondisclosure.

Over five years, TAL refused to pay out on 95 contracts due to alleged nondisclosure.

We’re going to look at a case study, who we’ll again refer to as “the insured”.

She applied for an income protection policy in February 2009 through an insurance consultant and an online application form.

The insured had to answer questions about whether she had ever had any medical conditions.

Had she ever had a mental or nervous disorder? The insured answered no. She also answered no to a question about whether she had been off work for more than five days due to an illness or injury not previously disclosed in the application. And she said she never had any condition for which she seeks medical advice not already disclosed.

She did however disclose that she had a knee reconstruction.

The application was referred to a human who asked for information about the insured’s occupation — she worked as a nurse — working hours and knee reconstruction.

The application was turned down because the applicant wasn’t working enough.

Then the underwriter eventually decided to accept the application, based on “borderline hours/professional role”.

She had also disclosed a wrist problem and an ear problem.

The policy was offered subject to an exclusion for her left knee that had been the subject of the knee reconstruction.

She had a 30 day waiting period and a monthly benefit of $2750, and a stepped premium starting at $125 a month.

Samantha Bailey 12.52pm: Freedom shares sink again

Meanwhile, outside the commission, shares in Freedom Insurance plunged as much as 12.5 per cent in early trade after the insurer said earnings for the current financial year were “uncertain”, due to the impact of ending outbound sales for some insurance.

The company today finally told the market it would stop outbound sales of some insurance after it copped a blast for revealing the overhaul at the banking royal commission on Tuesday, without providing any formal documentation about the decision.

12.41pm: Section 29 of the Insurance Contracts Act

Let’s look at the payment criteria for income protection claims.

Steps include “establish evidence”, “initial assessment”, and “withhold payment due to fraud/non disclosure”.

Ms van Eeden doesn’t think the third step is as important as the first two. But she says case managers look for fraud as part of their process.

Now we’re looking at the claims assessment guide.

It mentions “nondisclosure or misrepresentation”.

There are various remedies for this under section 29 of the Insurance Contracts Act.

There could be an innocent or negligent misrepresentation.

The remedy for innocent misrepresentation could be a voided policy or altered terms on a policy, but it would only be voided for a significant innocent misrepresentation.

But Ms van Eeden can’t think of an example of where this scenario might occur.

In some circumstances the policy would not be voided, but the terms may change.

Section 29 of the Insurance Contracts Act is about avoiding insurance contracts, senior counsel assisting Ms Orr suggests. Ms van Eeden would like to see this act in front of her as “there’s a lot of information”.

Ms van Eeden seems a slightly flustered at this point.

12.32pm ‘Every kind of report’

Over the past few years, the information that TAL requests to investigate claims has become more confined than it used to be.

In the past TAL would “go out and call for every kind of report that they could see” but now the company is ‘trying to be a lot more specific”, Ms van Eeden says.

Why did the company try to get every kind of report, in the past, asks Ms Orr.

To explore all avenues of investigation, Ms van Eeden says, to see if there’s anything that’s important that has not been provided, to assess if there’s a relevant medical condition that that hasn’t been disclosed.

Ms Orr seizes on this. Sso would TAL call for every kind of report, or only those that were relevant, she wants to know. Reports extended to “all sorts of irrelevant medical information”, Ms Orr suggests, and Ms van Eeden agrees that, yes, that happened at that time, to see if the claim could be denied for nondisclosure.

This was the case until about 2012 or 2013.

“It’s not acceptable and that’s why we have changed our processes,” Ms van Eeden says.

How are claims denied?

The case manager can recommend a claim be denied and they prepare a report to their team leader who considers if the claim should be declined.

Since 2016 the decision to decline a claim has to be approved by senior management.

12.25pm: TAL case management

TAL’s Ms van Eeden deals with three cases of policies sold through the retail channel in 2009, 2013 and 2014.

When someone wants to make a claim, TAL does an eligibility check. She concedes this is a very basic check to make sure the person is covered.

If someone wants to claim, they’re sent a claims pack or asked to participate in an interview. Then the claim is assigned to a case manager.

If the case manager needs to, they can get more information such as getting an independent medical examination, further underwriting opinion, undertaking surveillance of the claimant, getting information from treating health professionals, getting information from government departments or the person’s employer or credit reference agencies.

The customer has to give a signed authority for many of those information-gathering steps. And some of those steps are only taken when TAL considers them necessary, depending on the age and medical condition and occupation.

TAL has “roundtable conversations” where it has oversight of the case managers.

Ms van Eeden mentions that she wasn’t around during the earlier processes.

Senior counsel assisting Rowena Orr QC, wants to make sure that Ms van Eeden is going to be able to answer questions about things that happened before the witness started her job.

Ms van Eeden says she’ll be able to assist.

TAL tries to avoid multiple requests for information where possible, she says.

12.18pm: TAL’s Loraine van Eeden appears

We’re back from the break, and TAL general manager of claims Loraine van Eeden takes the stand.

TAL has about 18 per cent of the life insurance market. It sells to super fund trustees and employers as part of a group life insurance arrangement, through financial advisers and directly through comparator websites (the retail channel), and directly to consumers (the direct channel), we’re told.

Income protection cover is a significant part of TAL’s business. Close to half the life insurance policies sold by TAL have included income protection in each of the last five years.

How does a customer apply for a TAL insurance policy, Ms Orr asks.

It uses an “underwriting rules engine” — a software system — to assess online or phone applications.

Sometimes this system refers an application to a human, particularly if it’s a non-standard application.

It’s early days for Ms van Eeden’s evidence, but already, Ms Orr is having to work hard to get agreements to these basic details, with Ms van Eeden saying she hasn’t seen the statements of her colleagues that have provided this information.

12.08pm: PM’s ‘crocodile tears’

Meanwhile, outside the commission, Labor’s Clare O’Neill has said that the Prime Minister Scott Morrison was crying crocodile tears for the victims and never wanted the Royal Commission to happen.

11.57am: Review processes

Who does the medical definition reviews?

TAL has a team that reviews definitions. MLC has created a medical definitions review panel. Suncorp’s executive manager of product management completes the annual review. Westpac has a working group. AMP has a “propositions team”.

Onepath’s product team does its reviews, while MetLife has created a “product policy” to comply with the code.

AIA’s reviews happen through its product definitions review committee.

Zurich has a risk product working group.

CommInsure sets up a working group to review medical definitions.

Triggers across companies for medical definition changes outside formal review processes include market changes, legislative changes, competitor reviews and feedback from stakeholders.

What about reviews for off-sale products?

Many insurers have a similar product for off and on sale products, Ms Orr explains. TAL doesn’t though, and it will provide the next witness to appear at the hearing.

There is now a brief break to change witnesses.

11.50am: Industry issues

Ms Orr is now looking at medical definitions across the industry.

In response to queries from the commission, eight of the 10 largest insurers accepted there had been deficiencies in their response to updating medical definitions.

TAL didn’t have formal processes in place to review medical definitions annually until 2016.

AIA didn’t have a formal definition review policy until last year.

MLC didn’t have a definition review policy until last year.

Zurich didn’t have a formal process to review definitions for off-sale products until 2016 and recognised it had delayed in updating the definition of severe rheumatoid arthritis.

Metlife didn’t have regular reviews of medical definitions until 2016.

AMP didn’t have a formal review of medical definitions until last year.

Suncorp didn’t have a review framework and instead relied on informal processes and ad hoc medical definition updates but now intends to conduct reviews every three years.

Westpac didn’t find any deficiencies and CommInsure said it didn’t find any deficiencies except that its failure to update the heart attack definition was a “commercial misjudgment”.

In October 2016, after the media attention for CommInsure’s trauma policies, the Financial Services Council introduced the Life Insurance Code of Practice, which requires life insurers to review medical definitions in their policies at least every three years.

TAL, MLC, Suncorp, Westpac Onepath and AMP now review definitions annually. MetLife aims to review every 18 months. AIA seeks to review at least every three years but in practice reviews more often. And CMLA and Zurich said they aim to comply with the three year requirement.

11.42am: An apology, but no review

Despite the claim being paid, FOS wrote to CommInsure again, as it was investigating whether there was a systemic issue.

FOS asked CBA about other cases where CommInsure had declined trauma claims for breast cancer.

There were two claims denied because the policy required “radical breast surgery”.

FOS wrote to CommInsure again to say there was a systemic issue.

Ms Troup thinks this was “just an isolated event” and “we haven’t found in other circumstances where we had inappropriately declined a claim”.

Will CommInsure review past claims declined around “radical breast surgery”?

There has been no decision to do a review, and Ms Troup won’t commit to doing one.

She “would like to think about that further”, she tells Ms Orr.

CommInsure has updated its cancer definition and provided training so she thinks there’s a very small chance this will happen again.

Case managers will be told that “radical breast surgery” should be interpreted by level of tissue removed among other considerations.

Ms Troup also offers an apology for the process the insured had to go to while dealing with her health issue.

“I imagine it caused her additional stress and I apologise for that. Her claim should have been paid earlier and with, again apologise for that as well,” Ms Troup says.

Ms Orr is done questioning Ms Troup and Commissioner Hayne tells her she is excused.

11.34am: Claim finally paid

CBA’s Group Customer Relations team was handling the FOS dispute and asked the medical consultant to look at the case again.

The consultant still thought there was no evidence of “radical” surgery “as per the policy intent” — not the policy wording.

But CommInsure didn’t respond to FOS in the required time, which Ms Troup accepts fell below what the community would accept.

CommInsure continued to insist the claim would not be paid.

There was a phone conference with CommInsure and the insured, with CommInsure representatives given authority to settle for up to $84,650 or half the insured sum of $169,305, in recognition “radical” surgery hadn’t been defined.

The claim didn’t settle.

FOS ruled that CommInsure wasn’t entitled to deny the claim because the policy doesn’t define “radical breast surgery” and the applicant provided medical documents saying she had “radical breast surgery”.

CommInsure accepted the recommendation and paid the claim for $169,305 plus interest of $5000.

Ms Troup accepts FOS made the right decision and the company’s claim handling caused the insured distress.

11.29am: More old definitions

Now CommInsure was relying on an 18 year old medical definition and imposing limitations on the definition that weren’t expressed in its policy documents, and not accounting for the insured’s doctors’ opinions.

Ms Troup concedes this was not acceptable, and points to the company’s “processes and procedures”as a point of failure.

She concedes the way CommInsure handled the claim fell short of the standards the community would expect, and accepts CommInusr breached its good faith duty.

The insured complained to FOS.

Another letter from her GP says that if the insured’s condition had occurred about 20 years ago when the policy was taken out, treatment would probably have resulted in a mastectomy, but it’s now current practice that the insured’s condition would be treated with breast conserving surgery and radiotherapy.

Ms Troup concedes medical practice had moved on.

“But the intent of the policy was the exclusion was carcinoma in situ unless it resulted in entire removal of the breast,” she says.

Then in May 2017 the definition was updated. Cancer was defined to include carcinoma in situ of the breast resulting in the removal of the entire breast OR breast conserving surgery and radiotherapy OR breast conserving surgery and chemotherapy.

But CommInsure didn’t backdate the definition. So it didn’t apply to the insured.

Ms Troup thinks the 1998 cancer definition wasn’t out of date.

11.21am: Two doctors letters but claim denied

The insured and her husband wrote to CommInsure and provided further information from the GP and the surgeon. They said that the policy does not define “radical” and speculated that it might mean a mastectomy.

The surgeon added a handwritten note: “The treatment received is radical because radiotherapy was required as an alternative to mastectomy.”

The insured wrote that she understands “the ample nature of my breasts meant that I did not require a mastectomy” and had her breasts been “small” she would have required a mastectomy.

The surgeon confirmed that statement.

The GP also provided a letter saying the patient had “radical breast surgery/treatment”.

The claim was assigned to a new case manager.

The medical consultant again said “radical” breast surgery had not been performed.

The claim was referred to a committee that considered her case and endorsed the recommendation to decline the claim.

CommInsure wrote to the insured: “We appreciate that ‘radical’ surgery is not defined in the relevant product disclosure statement. However radical surgery pertaining to the breast means radical mastectomy which is defined as removal of the entire affected breast.”

The insured had now provided two doctor letters but CommInsure declined the claim.

11.12am: Claim declined

We look at the insured’s claim form, lodged after she developed breast cancer.

She ticked “cancer” and there’s a box to describe symptoms that preceded the diagnosis — a regular mammogram identified the abnormality. She had no symptoms prior to diagnosis.

She had surgery and provided information from her GP, surgeon and radiation oncologist.

The GP said this was a carcinoma in situ, which did not require removal of the entire organ, but surgery was performed to arrest the spread of malignancy.

What surgery was performed? The removal of a portion of breast tissue measuring 33 by 27 by 12mm. The other surgery involved removing 50 by 30 by 8mm of breast tissue.

The CommInsure internal medical consultant said the claim didn’t meet the policy definition of cancer because this was a carcinoma in situ and the treatment didn’t involve “radical breast surgery”.

CommInsure denied the insured’s claim.

CommInsure wrote to the insured, saying carcinoma in situ is excluded “unless leading to radical breast surgery. Therefore it is with regret and without prejudice to any other defences we may have that we have declined your claim”.

The letter didn’t explain why the insured’s treatment was not “radical” breast surgery and it didn’t say anything about what CommInsure considered “radical” breast surgery AND “radical” breast surgery wasn’t defined anywhere in the insured’s policy.

Did this letter provide an adequate explanation for declining the claim?

Ms Troup says at the time the company thought it did — the general understanding of “radical” surgery was a mastectomy — but admits the company didn’t explain that.

11.02am: A new case study

The commission is going to look at another case study of a CommInsure customer who developed breast cancer. With a suppression order in place, she’ll be referred to as “the insured”.

The customer took out a total care plan with Legal and General in 1996, which was acquired by Colonial and became part of CommInsure.

The policy says the “recuperator benefit” pays a lump sum on diagnosis of cancer, except for cancer that occurs within three months of the policy commencing.

The insured took out “recuperator” or trauma cover as part of the policy. The conditions were defined in the policy.

The definitions were updated sometimes and the insured was entitled to rely on the definition that applied at purchase or any updated definition.

There was one definition that applied at purchase in Feb 1996, then it was updated in April 1996 and November 1998, then was not updated again until May 2017, almost 20 years later.

When the insured made her claim the November 1998 definition of cancer was in force: “malignant tumours” including cancers that are completely untreatable.

One of the exclusions was “carcinoma in situ unless leading to radical breast surgery”.

The claim was made in August 2016 and the insured had held the policy for more than 20 years. Again, the definition of cancer in the policy was almost 18 years old.

10.55am: Claims reviewed

Deloitte conducted a review of CommInsure’s claims declined from 2011 to 2016.

Deloitte reviewed a sample of 797 declined claims. There were four possible outcomes for each: to be marked appropriate, appropriate with poor customer experience, a customer financial impact, or an incomplete process.

Deloitte found problems with 41 claims and sent them back to CBA for reassessment.

The reassessment found there were 12 cases where the decision was right, but where there was also a poor customer experience. Eight cases had an incorrect decision leading to financial impact for the customer, and 11 still being reassessed when the report was published. Among those 11, a further two had the correct decision but a poor customer experience.

For a total of 14 cases, 12 from the report plus two from this document, where the decision was correct with poor customer experience, and a total of 16 with a customer financial impact.

CBA remediated the customers.

Deloitte made 29 recommendations such as improving staff training, improving how case managers document their conclusions, improving documents used to communicate with customers, improving how quality assurance reviews worked, improving processes for ex gratia payments.

CommInsure has implemented the 29 recommendations.

Key changes include — claims managers have to do a checklist before they complete a claim, and there’s a training program every time a change is implemented.

10.48am: CommInsure’s dealings with ASIC

Helpfully for those of us following the hearings, Ms Orr now summarises CommInsure’s dealings with ASIC.

- ASIC gave CommInsure advance notice of its findings.

- CommInsure had conversations with ASIC about what would be included in ASIC’s media release — that is the decision to backdate the medical definition for heart attacks to 2012, which ASIC included in the media release.

- FOS told ASIC it thought CommInsure had engaged in serious misconduct, and then ASIC sent CommInsure a letter.

- When ASIC decided CommInsure engaged in misleading conduct it took no enforcement action but agreed on a $300k community benefit payment and gave CommInsure the opportunity to make changes to the media release. CommInsure has never acknowledged until today its ads were misleading.

10.45am: No acknowledgment of wrongdoing

Has CommInsure ever acknowledged its ads were misleading before now?

Ms Troup says the company didn’t entirely agree with ASIC’s concerns.

At that time CommInsure was “still defending our position” but now, “I can see how ASIC’s concerns were legitimate,” Ms Troup says.

Yes, she agrees that the ads were misleading, but CommInsure has not publicly acknowledged that before her evidence today.

Let’s see the final media release.

It has no acknowledgment by CommInsure that the ads may have been misleading, and it doesn’t even have a CommInsure acknowledgment that ASIC’s concerns about the ads were “reasonably held”.

And it has no admission of wrongdoing by CommInsure.

The media release records CommInsure’s $300,000 community benefit payment and a reference to CommInsure commissioning the compliance review of its advertising.

CommInsure then did the review of its ads.

Wasn’t this a very good outcome for CBA?

No, Ms Troup doesn’t think so, because the company thought it had “elements of defence”.

Commissioner Kenneth Hayne interjects again, wanting to know what those defences were.

The context of the advertising, Ms Troup says, and that consumers would understand that an insurance policy has defined terms.

Mr Hayne wants to know if a consumer would think that if the doctor said they had a heart attack, they had a heart attack. Ms Troup concedes that’s reasonable, but insists policies have term.

If CommInsure did something wrong, was it punished, the Commissioner asks.

Yes, the company felt the community benefit $300,000 payment was a form of punishment.

The commissioner puts some perspective around that amount of money. It was Three times the claim of the insured person who forms the basis of the case study, he puts it to Ms Truop. When the punishment for misleading conduct is $2 million for a corporate entity and there were at least four ads, meaning a maximum $8 million punishment, he suggests.

Mr Hayne: “Did CommInsure come out of this process thinking that it had been punished or brought to book?”

Ms Troup: “Yes, we did sir.”

10.36am: CBA’s words, ASIC’s media release

CBA’s James Myerscough replied to ASIC with a draft of a letter resolving the matter between ASIC and CommInsure.

Ms Orr: “So CBA suggested to ASIC what ASIC should say in its media release?”

Ms Troup: “It provided feedback yes.”

Ms Orr: “With a different form of words for ASIC to use in its media release?”

Ms Troup: “Yes.”

Ms Troup was involved in the drafting.

Mr Mullaly’s draft had an acknowledgment by CommInsure that its statements may have been misleading.

The same line in CBA’s draft read: “CommInsure acknowledges that prior to March 2016, ASIC’s concerns could be reasonably held”.

Did ASIC accept CBA’s suggested wording?

Let’s look at a letter from ASIC’s Tim Mullaly to Ms Troup.

Mr Mullaly says the ads contained misleading representations.

And further, ASIC’s concerns extended beyond the four ads because there was substantially similar wording in other ads.

He suggests action to be taken by CommInsure: that the company would acknowledge that ASIC’s concerns “could be reasonably held”.

This is the wording from CommInsure’s draft!

10.27am: Regulator asking the regulated?

Did ASIC take any enforcement action against CommInsure over these ads, asks Ms Orr.

Ms Troup says the two parties “did come to an agreement”.

We look at an email from ASIC’s financial services enforcement boss Tim Mullaly.

Mr Mullaly writes of some wording that would form the basis of a letter between ASIC and CommInsure resolving the letter, and form the basis of an ASIC media release.

The wording had references to CommInsure making misleading and deceptive statements on its websites, making customers think they would get a payment for a heart attack when they would only get a payment for a heart attack meeting certain definitions.

The proposed wording had CommInsure acknowledging the statements may have been misleading, with CommInsure offering a community benefit payment of $300,000 and commissioning an independent review of its advertising.

And ASIC said it had concluded its investigation into CommInsure.

Mr Mullaly added that the body would need to agree with CommInsure the timing of the payment, the recipient and details of the review.

Ms Troup doesn’t remember how the $300,000 figure was decided.

The maximum penalty for a contravention of section 12DB of the ASIC Act for misleading and deceptive conduct was 10,000 penalty units, almost $2m per contravention, MS Orr points out.

Commissioner Kenneth Hayne interjects with a question, for what we think is the first time in this round of hearings.

What does ASIC mean by “let us know whether this is sufficient for CommInsure to resolve”, he wants to know Is this a case of “the regulator asking the regulated” about its alleged breach of the law?

Ms Troup says CommInsure could have continued to defend its position, and ASIC always reserves the right to continue the enforcement action, although this correspondence doesn’t suggest any further enforcement action.

10.20am: Problem pamphlet

The commission sees another pamphlet that was on the CommInsure website from June 2015 to March 2016.

Again, it says that trauma cover pays a lump sum benefit for heart attack.

But there’s some detail this time.

A heading reads: “What is a heart attack?”

Two paragraphs describe how fast the heart beats, explaining a heart attack happens when one or several of the heart’s main arteries are blocked and oxygen-rich blood no longer reaches it.

That’s not how heart attack was defined in the policy, and the page doesn’t refer to the definition of heart attack in the policy, Ms Troup admits.

Yes, someone reading would have been likely to believe CommInsure’s trauma policy covered all heart attacks and the document was misleading, she concedes.

10.16am: Misleading definitions

Let’s look at another page that was on the CBA website, from June 2013 to March 2016.

It says trauma cover can pay a lump sum if someone suffers a heart attack.

There’s no indication that “heart attack” only included some heart attacks, and no reference to “heart attacks of specified severity”, Ms Orr points out.

Ms Troup accepts someone reading the ad would have been likely to believe the trauma policy covered all heart attacks. She accepts this ad misled customers.

We now look at a two-page pamphlet that was on the CommInsure website from June 2015 to March 2016.

The pamphlet says “heart attack” is covered in trauma cover.

By June 2015 the policy didn’t say “heart attack”, it said “heart attack of specified severity”.

But there’s no reference to the definition from the policy, and there’s not even a reference to the PDS.

Yes, someone reading would have thought the trauma policy covered all heart attacks and this pamphlet was also misleading, Ms Troup admits.

10.11am: Consumers misled

Aha — the document is on display.

It’s an extract from the CBA website from Dec. 2012 to March 2016.

It provides information about trauma cover, saying it can pay a lump sum for specified trauma conditions such as cancer, heart attack or stroke.

But there was no indication on these pages that “heart attack” was intended to cover only some types of heart attack.

Ms Troup points out that there was a link to the product disclosure statement. It’s right at the bottom.

But there was no indication that the heart attack should be read as “heart attack of specified severity” on the web pages, Ms Orr says.

Ms Troup accepts someone reading the ad would be likely to believe the trauma policy covered all heart attacks.

Yes, it would be reasonable for a reader to expect CBA has accurately summarised its policy in the ad and not overstated the coverage available. And it’s not reasonable to expect someone to scroll much further down and click on the PDS and find the heart attack definition, Ms Troup admits.

So this ad was misleading to consumers about the coverage of trauma policies for heart attacks, she admits.

9.59am: A glitch and a pause

Ms Orr wants to show the commission a particular document but the court system isn’t co-operating this morning.

Should the hearing stand down for a few minutes?

Commissioner Kenneth Hayne AC QC: “If I sit here and stare balefully at the screen it will work quicker, won’t it, Ms Orr?”

A pause.

Ms Orr: “We think it may be another few minutes, Commissioner.”

Mr Hayne: “Rather than my staring at everybody and causing havoc, if I leave and if you let me know when we’re ready to go.”

We’re having a quick break and waiting.

9.53am: Heart attack ads

And we’re underway.

First up, senior counsel assisting the commission Rowena Orr QC needs to tender several CommInsure draft product design descriptions after her evidence yesterday.

Now she’s going to return to a letter that ASIC sent to CommInsure warning of “serious misconduct”.

She’s already looked at out of date medical definitions that are raised in the letter.

Now she’s going to look at CommInsure’s advertising and promotion of heart attack cover.

Until March 2016 CommInsure heart attack cover only applied to severe heart attacks.

ASIC’s Peter Kell wrote to CommInsure warning that ads on CBA’s website and information given to financial advisers were misleading and deceptive — meaning CBA was breaching its obligation to act in utmost good faith under the Insurance Contracts Act.

The concern was that statements in the ads weren’t sufficiently qualified to allow readers to understand the criteria to meet the heart attack definition.

Mr Kell wrote that ASIC was considering enforcement options.

9.25am: Preview

Good morning and welcome to the fourth day of the insurance round of the financial services royal commission.

This morning CBA will be back in the spotlight, with former CommInsure boss Helen Troup set to return for more grilling from senior counsel assisting the commission Rowena Orr QC.

Ms Troup yesterday admitted that the company made a commercial decision not to backdate new medical definitions as far back as its own experts recommended, for fear it would have to pay out more money in life insurance claims.

The company also misled the Financial Ombudsman Service when one customer complained about not getting a full payout despite suffering a heart attack and ignored the ombudsman’s findings, in behaviour that corporate regulator ASIC labelled “serious misconduct” but failed to take any action against.

Next up will be TAL general manager of claims Loraine van Eeden. TAL is buying Suncorp’s Australian life insurance business for about $725 million.

The hearing will start at 9.45am

8.25am: Heart attack definitions

Defining what constitutes a heart attack was the subject of many questions during Wednesday’s hearing.

7.45am: Witness list

The royal commission has listed just two witnesses due to appear today.

- Helen Troup, from Commonwealth Bank’s CMLA

- Loraine van Eeden from TAL

Royal commission insurance round hearings

Wednesday 12 September: ‘May discriminate, impact profit’

Tuesday 11 Spetember: ‘Warning signs were all there’

Monday 10 September: ‘I’d sack them’

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout