Australian billionaire Ed Craven on what keeps him ambitious

Yes, 29-year-old billionaire Ed Craven now takes more in traditional currency than crypto, but it’s not like he’s losing his edge, or his ambition.

Ed Craven is heading for the straight and narrow.

Where his Stake.com global gambling giant was once a cryptocurrency-only online casino and betting empire, the business has been transformed into one now suddenly taking 70 per cent in boring old traditional, or “fiat” currency.

Stake, domiciled in the Caribbean tax haven of Curaçao and often shrouded in secrecy, has started applying for and gaining government-issued gambling licences around the world. It could even lodge paperwork for an Australian bookmaking licence this year.

It’s not that the 29-year-old billionaire Craven – who owns the majority of Stake with his American business partner, Bijan Tehrani – is losing his edge, or his ambition.

Not content with building one of the world’s biggest gambling operations from a low-key art deco building in Melbourne’s CBD, he and Tehrani already have established another technology “unicorn” in streaming service Kick.

All they want to do with Kick is to take on and one day beat Amazon-owned live streaming platform Twitch, and to a lesser extent YouTube.

It sounds daunting, especially given one analyst in 2023 slapped a $US46bn ($72bn) overall valuation on Twitch. But the quietly-spoken Craven confidently asserts he will beat those global giants at their own game one day. Just like he has in the betting sector.

Beyond that, he and Tehrani have even bigger plans for their business empire to one day be “the Australian version of Disney”.

That doesn’t necessarily mean theme parks, but following the lead of Disney (which now owns a US gambling brand, ESPN BET) in building out their holdings via their Australian-domiciled Easygo services arm into a wider entertainment empire.

Easygo has its own gaming studios, Twist and Massive, to build iGames such as slot and casino games for Stake and other online gambling companies. Massive has a target of building 24 new games annually.

It has also established the Carrot remote gaming server business, a backend system to host and manage online casino games.

Craven calls the new business’s contribution to the overall Easygo company “astonishing” after just a year of operation.

For now, though, much of Craven’s attention is on his two global concerns: the transformation – and legitimisation – of Stake, and the emergence of Kick.

That is a lot for any entrepreneur to have on their plate, let alone one who also holds the title of Australia’s youngest billionaire.

But in an interview with The List, Craven admits he has been chastened by some of the difficulties he’s experienced with Kick, and the controversies he has had to deal with both there and also at Stake. Like most other entrepreneurs, he has – for the first time in his still-fledging career – faced some ups and downs, and had to learn quick lessons.

“I think with Kick, and entering this live-streaming space, has certainly been one of the more humbling experiences,” Craven reflects.

“I think, probably, we approached this thinking it would be easy. We’ve managed to conquer this big market share in the gaming space [with Stake] and thought, ’well, this live-streaming space comparatively is not that complicated’.

“But very quickly you realise … you have to make all the same mistakes again, go through all the potholes, through the lows, and ride the highs again. You end up stretching yourself very thin.”

Craven estimates Kick has about a 14 per cent market share in the live-streaming market against Twitch’s 86 per cent. It isn’t close to breaking even yet, but is averaging between 500,000 to 700,000 viewers per day worldwide on 4000 to 7000 concurrent live channels, with 2.2 billion hours watched since it launched in October 2022. There are 54 million accounts on the platform, and Craven says it is strongest in Spanish- and Arabic-speaking markets, and in Turkey.

Certainly in revenue and profit terms, Stake is far bigger than Kick and demands more of Craven’s time – though he does host his own Kick streaming show on Saturday nights, and admits to being absorbed in the platform’s potential.

“Naturally, I think the best decision as a business owner is to continue to emphasise the most time there [at Stake]. But Kick is fascinating. It’s such an incredibly fun industry. I absolutely love it. It’s so exciting and there is never a dull moment. So I think in terms of free time on the weekends for me, it definitely soaks that up very quickly.”

The financial numbers around Stake are staggering, especially given Craven and Tehrani, now 31, only launched it in 2017 with an idea of simply running an online casino using cryptocurrency, which was then in its infancy.

The pair met during high school on a popular fantasy dragon-slaying website called Runescape, got busted operating an illegal casino within the game, and were banned in 2011 – all while still teenagers.

They parlayed that experience into a cryptocurrency-friendly dice game called Primedice that launched in 2012, keeping their profit margins low and incentives high to attract players.

After a rocky start when it was haemorrhaging money almost immediately, losing the pair between $10,000 and $20,000 per game, Primedice began making profits. By September 2014, Primedice had recorded its billionth bet.

Craven and Tehrani would later survive a $1m hack attack, and still hadn’t met each other before the latter travelled to Australia for the first time in 2016.

Tehrani now has Australian residency and splits his time between the US and Australia. He is not yet eligible for the Richest 250, but is undertaking the necessary processes to eventually gain citizenship.

In just eight years, Stake has become a behemoth. There are about 21 million Stake account holders around the world, and it had gross revenue – the difference between the amount wagered by punters and the amount won – of more than $US4.5bn ($7.05bn) in 2024.

The Financial Times reported in 2023 that Stake’s gross revenue was then almost $US2.6 billion.

Figures seen by The List suggest Stake’s net profits easily exceed the $1bn mark. Craven says Canada is a big market for the company (outside Ontario, where it is trying to gain a licence), as is India and South American countries including Brazil and Colombia. He is also keen to expand in big African markets such as Nigeria, and potentially in Asia as well.

In Australia, EasyGoSolutions Pty Ltd, an entity that provides services to Stake and Kick, made a pre-tax profit of $308m in 2023 and paid more than $100m in corporate tax, documents lodged with the Australian Securities and Investments Commission showed.

Easygo’s $206m net profit that year was one of the biggest by a privately-owned Australian business and came after it made net profits of $74m and $76m in 2022 and 2021 respectively.

Revenue in 2024 is estimated to be more than $500m, and net profit at least $260m.

Easygo has about 500 staff in Australia, and there are at least 1200 employees across Craven’s wider business empire including offices in Serbia, Italy, Brazil, Peru and Colombia.

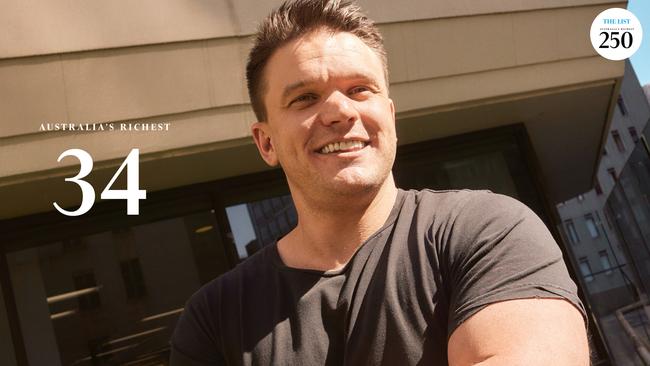

It all adds up to a big fortune on paper for Craven, who places 34th this year on The List with estimated wealth of $4.53bn.

Stake has now gained mainstream government-issued licences in markets including Brazil, Italy, Peru and Colombia. Its Denmark licence is pending approval (in January it acquired the licenced MocinoPlay there), as is one in Canada’s Ontario province.

Rumours abound that Stake wants a licence in Australia, fed by Craven’s presence in Darwin – where online bookmakers are regulated – in February, where he met regulators and territory government officials.

Craven plays a straight bat to questions about Stake operating in Australia as a potential rival to the likes of Sportsbet, Ladbrokes and Tabcorp, and smaller ASX-listed firms such as BlueBet and PointsBet (Craven’s business has a shareholding in the latter).

“We have a lot going on globally. We’ve obtained seven licences in the last 25 months; six in the last six months alone,” he says.

“Australia right now would be a large undertaking. But of course, it’s an exciting project and an exciting prospect potentially getting involved.”

An entry to Australia would not feature cryptocurrency betting given its longstanding ban here, but Craven points out Stake now has plenty of experience and success in taking regulated bets in traditional currency.

That is at least in part due to government regulations effectively “catching up” to companies like Stake. With regulation comes taxes that flow to governments, and usually also contracts with sports with which betting companies have markets for their matches and contests. (In Australia these are known as “race fields fees” or “product fees”.)

“A lot of the gaming market was heavily focused on countries like the UK, on entry into the United States, on countries like Australia,” Craven explains.

“Where Stake did things a little bit differently [was] realising that the whole world was open for business in a pre-regulated framework. And these markets were potentially incredibly lucrative.

“And now governments and regulators are starting to say ’hold on a second, we need to be involved here’. And we are incredibly cooperative with that and have been fortunate to be involved in these discussions. So making sure that we’re ahead of the curve and working alongside what these frameworks are going to look like as early as possible is incredibly important for the longevity of the business over the next 10, 20 and 30 years.”

Craven can also see growth opportunities for Stake in going after market share in the regulated part of its sector, given it is reaching saturation point in the cryptocurrency betting mass market.

“We’re very confident that Stake doesn’t have as much room to grow in crypto as it does in traditional payment methods. So we did put a lot of emphasis in these last two to three years on pivoting from crypto, understanding that the opportunity to grow there wasn’t as large as, say, entering more traditional markets,” he says.

“At the same time, we still very much protect our crypto market share and keep a close eye on that. So we’re not losing focus on maintaining that unique selling point, which we’ve had from the get-go.”

There’s almost always a whiff of controversy about most gambling companies. In Stake’s case, its notoriety has come from its secretive nature, its predominantly operation in unregulated markets (or, as Craven calls them, “pre-regulation”) and that it is licensed in Curaçao, a Caribbean tax haven.

The fact it started by just taking bets in cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin and Dogecoin from punters – a means of gambling banned in Australia – has also raised eyebrows. As has some controversial advertising featuring Stake branding.

In February, Stake attracted headlines when its branding was seen on social media advertising and posts for UK adult content creator Bonnie Blue, who had posted videos about visiting a university in Nottingham to have sex with 18-year-olds.

Related or not, Stake said in March it was withdrawing from the UK market where it was operating via a white label firm based on the Isle of Man called TGP Europe.

“We have no association with Bonnie Blue, no sponsorship with her,” Craven says. He explains that Stake branding was superimposed on her content – likely by an affiliate earning income from clicks associated with her or the Stake brand – and appropriate steps were taken to have it removed once Craven became aware.

Regarding Stake’s UK exit, Craven says: “We’ve had a relationship with TGP for three and a bit years. But at the end of the day, we decided it wasn’t worth pursuing. The effort is better spent elsewhere. The UK contributed less than 0.1 per cent of our business. So we came to an agreement to part ways.”

The 2025 edition of The List – Australia’s Richest 250 is published on Friday in The Australian and online at www.richest250.com.au

He says Stake could re-enter the UK market at a later date but only with a “better and more competitive product offering”. It will continue to sponsor struggling English Premier League team Everton, because its games are telecast around the world.

Kick, meanwhile, has also had its challenges. The business was started soon after Twitch banned streaming live gambling on its platform in 2022. Before then, Canadian star rapper Drake had often livestreamed his Stake gambling sessions on Twitch.

Kick offered multimillion dollar contracts to top streamers and takes just 5 per cent of all streamers’ earnings, compared to the 50-50 split on Twitch. That has helped to attract some Twitch stars and lesser-known content creators, who say they earn more on Craven and Tehrani’s platform. Craven, a keen streaming fan since his teenage years, often donates money himself to Kick streamers.

While Kick grew quickly, it had clear issues with what seemed to be – by accident or design – a more relaxed approach to regulating content. It resulted in negative headlines including Kick being described as a “playground for degenerates” which allowed anti Semitism, racism and sexism to run rife.

Craven admits to being “caught off-guard” by the size of the issue in trying to control and monitor content on a platform with tens of thousands of daily active streamers.

“How the platform is used is very different from, say, a gaming company, where there are only very few aspects you can use. It’s something that opens up a whole range of problems which we did not even know would ever possibly exist,” he says.

“And the resourcing and the talent and the set of skills you need to be able to solve that is very different. So we’ve had to adapt to this very different way of doing business and build the company up, and simultaneously learn all these lessons which our competitors had been learning for the last 10 to 20 years.”

He claims Kick has “leant very, very heavily into artificial intelligence to try to help with the moderating and proactively take down these [offensive or problematic] streams which are going to cause us problems, before they become problems.

“It’s the one thing that doesn’t get reported. For every person that causes a negative headline, there are hundreds, if not thousands, proactively taken down, and well and truly ahead of [issues].

“I think the last six months especially, we’ve really tightened things up and got ourselves to a place where we’re very confident that we’re balancing not only people’s ability to create amazing content, which people find entertaining, but also ensuring that it’s not utilising the platform for the wrong means.”

Craven has also rejected suggestions that the reason he created Kick was to promote Stake by paying streamers to gamble live on the site. “I don’t blame people for making that assumption. But we are not doing it for that reason.”

He gives an example of Turkey, where he claims Kick has secured about 80 per cent of the Turkish-speaking market and where no gambling is streamed.

Within the livestream market, Kick claims to also about 40 per cent of Spanish speakers and 90 per cent of the fledgling Arabic market, plus a good presence in Poland.

But it is that 14 per cent overall market share versus Twitch that he is most closely watching.

As a believer in the network effect – when the value of a platform product increases because the number of users increases, causing the network itself to grow – Craven ambitiously forecasts Kick to rival and one day surpass its far bigger rival.

“If we can cross that 50 per cent mark, then things will grow exponentially. We certainly want that bigger market share [than Twitch] one day. And I think we can get there.”

All of this will be done from Australia, where Craven spends most of his time. He jokes that his lawyers and accountants tell him he’d be better off domiciled overseas, but wants Easygo to become one of the biggest tech companies in Australia.

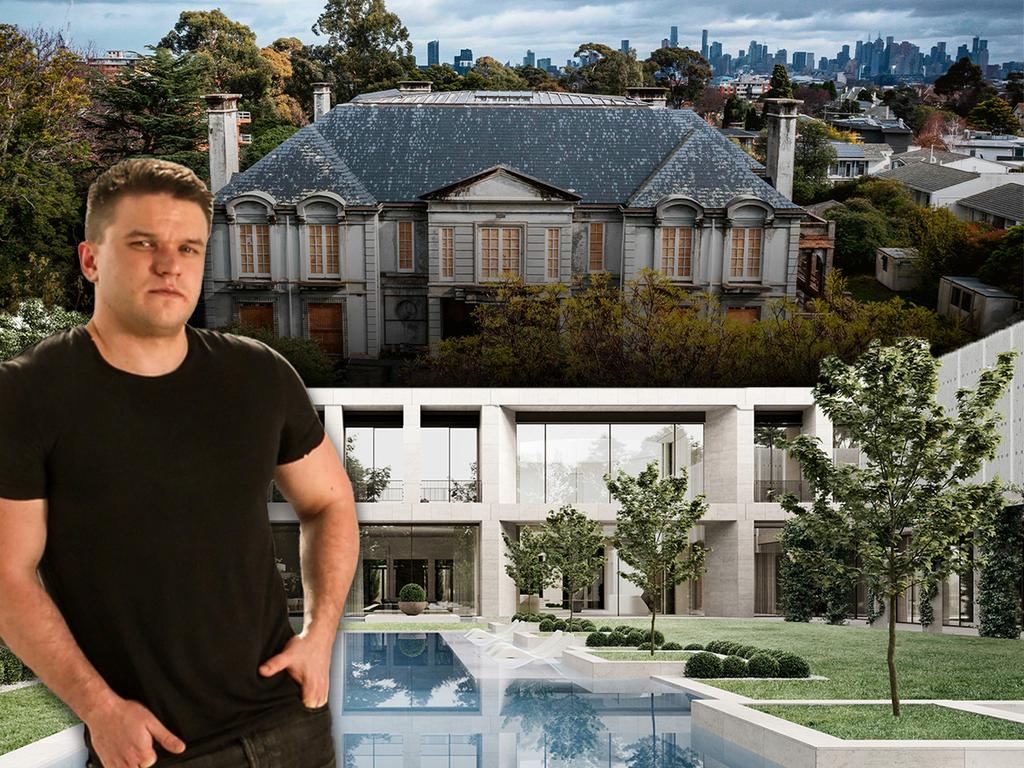

He’s also got the not-so-small matter of the massive $145m overhaul of the Toorak “ghost mansion” he bought in Melbourne for about $80m in 2022. “It’s slow and steady there. Like Kick, it ended up being a lot to bite off, for sure, but it’s fine,” Craven jokes.

Ultimately, his biggest plan is to keep growing Stake and Kick and see where else the business can take him in the entertainment space. He might just end up building another big global brand in his 30s and beyond.

“Now we don’t just look at things and say ‘let’s expand into all these amazing markets throughout the gambling world’. We go, ‘what other verticals of entertainment can we enter?’.

“We’ve proven ourselves a couple of times now. So what other opportunities are out there? I think that’s super exciting.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout