Australia needs to back its manufacturing wins with capital and a coherent policy

Governments of all stripes have tried to halt the seemingly inexorable decline of Australian manufacturing for two decades. The recent Olympics could have just been the clue.

In April this year, a tiny satellite developed by Adelaide-based Fleet Space Technologies was launched atop a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, to join a constellation of its colleagues orbiting the globe and helping to look for critical minerals.

In Queensland, Gilmour Space Technologies is aiming to soon offer the ability to launch payloads into low earth orbit using its 25m, Australian-designed-and-built Eris orbital launch vehicles. Back on earth, Redarc has grown over four decades into one of the pre-eminent aftermarket 4WD and recreational vehicle accessories suppliers internationally. It’s now expanding into defence and space in anticipation of the huge opportunities to come from defence shipbuilding programs in coming years.

This is an article from The List: Innovators 2024, which is announced in full on October 18.

All are examples of Australian manufacturing success stories, and there are many more like them. The reality, however, is there are still far too few.

For the past two decades, governments of all stripes have tried to halt the seemingly inexorable decline of Australian manufacturing, with the shuttering of vehicle production by Mitsubishi, Holden, Ford and Toyota – all within 10 years – the most public examples.

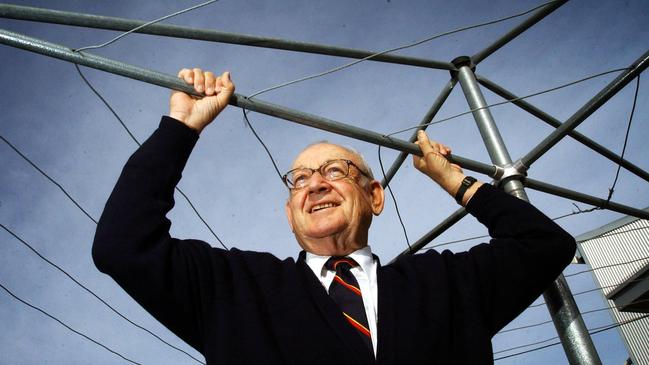

Manufacturer Hills Industries, born out of the development and manufacture of the iconic Hills hoist – such a staple of Australian life it featured in the closing ceremony of the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games – was an early bellwether of the headwinds facing the industry. After growing from a backyard business in 1940s Adelaide, the company diversified into manufacturing tools, steel products, rainwater tanks and more. During the 1990s, and more severely into the 2000s, it found itself unable to compete with cheaper imports from Asia and dwindled rapidly, becoming a shadow of its former self.

Its fortunes stand as a stark example that, as a high-wage jurisdiction, Australia cannot compete on price in a globalised economy. This was proved by the exit of car manufacturing, where the industry had been a mainstay, particularly in South Australia, since the 1950s.

Overall figures around the state of manufacturing in Australia make grim reading. A federal government report released late last year, Sovereign, smart, sustainable: Driving advanced manufacturing in Australia, strikes a sombre tone.

“In the 1960s, manufacturing represented approximately 30 per cent of both Australia’s gross domestic product (GDP) and employment,” the report says. “It is now 5.2 per cent of GDP and 6.5 per cent of employment. Australia can and must reverse this decline to secure our domestic capability and to become a globally competitive exporter.”

One of the difficulties with manufacturing, argue industry experts such as the Advanced Manufacturing Growth Centre’s managing director, Jens Goennemann, is that it is not a monolithic sector like mining, where one-size-fits-all policies, such as tax incentives, might work.

The government’s report recognises this, and also that the sector is dominated by many smaller companies. “Small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs) make up the majority of Australian manufacturers,” the report says. “Their ability to adopt Industry 4.0 technologies

can be hampered by lack of investment capital.

“The Australian government can help address this barrier by leaning into its ‘Buy Australian’ procurement policy, and by ensuring funding programs are easily navigable by SMEs. This will bring ‘bang for the buck’ in government procurement, and lead to increased levels of private investment.”

The report recognises the need to improve in areas such as skills development and collaboration between research institutions and business – once again, conclusions that are old news to those working in the sector.

The Future Made in Australia program, launched with much fanfare earlier this year, focuses heavily on areas such as value-adding minerals. Also under its remit are already-announced programs such as Hydrogen Headstart and the $1bn Solar Sunshot program, which sought to develop an Australian-based solar panel manufacturing industry with a focus on the NSW Hunter Region, to replace jobs lost from the closure of coal-fired power stations.

Eminent economist Chris Richardson derided that idea as “spectacularly dumb”, given Australia would be looking to compete with well-established players in countries such as China with vastly more expertise and a lower cost base.

“It’s just a waste of money,” he said at the time of the policy launch. “It’s the equivalent of asking taxpayers to smoke $100 notes.” Dr Goennemann points to examples of successful programs overseas. One, Germany’s Fraunhofer Institute, employs more than 32,000 people – mainly scientists and engineers – who focus on research in key future technologies then transfer those findings to industry.

But here in Australia there has not been a consistent or effective industry policy at a national level over the past decade, Dr Goennemann says.

“Good policy should be developed in collaboration with those it aims to assist,” he says. “However, Australia’s past policies have been piecemeal at best, consisting of a disjointed range of initiatives that provide temporary sugar hits rather than fostering well-informed, long-term industry and capability transformation.

“Efforts to replicate successful and impactful overseas initiatives have been short-term or lacking in strong political leadership. Frequent elections contribute to shifting priorities, and fast rotations of public servants in the industry department inevitably undermine continuity in any industry program and create knowledge gaps.”

Dr Goennemann says politicians also need to get over the idea that picking winners is a bad strategy.

“Our Olympic athletes have just returned from Australia’s most successful games ever and it wasn’t by chance,’’ he says. “It was because the Australian Institute of Sport identified and supported potential winners. Being overly egalitarian doesn’t win medals.”

He goes on to say a vital part of the national manufacturing strategy must be an industry-led body to co-ordinate programs and policies: “There should be an independent, centralised information and co-ordination body that federal, state and local government can tap into to ensure all initiatives from all levels of government are pointing at common goals.

“Secondly, we should undertake a complete mapping of Australian manufacturing capability against the Future Made in Australia aims. This would allow us to better understand the skills we have and what we do with them, and conversely, where we should improve our national capabilities.

“Third, we need to address the ugly truth that many highly capable Australian manufacturers struggle to scale due to difficulties in raising capital and a lack of access to effective funding mechanisms. We need an industry-led co-investment fund to help scale, retain and grow local manufacturers.”

Dr Goennemann cautions that “lucky Australia stands at a crossroads”.

“One path leads to a future reliant on commodities, for which much of the demand will wane,” he says. “When our luck runs out, and we have done little to nothing, we will look back on impactful decisions we failed to make when we had the chance, leaving our children and grandchildren worse off.

“The other path leads to a future supported by a nation of highly capable manufacturers who can deploy their skills to create complex and competitive products.”

One industry expert looking to position the nation to take advantage of the next phase of manufacturing innovation is Giselle Rampersad, Dean of Education at Flinders University’s College of Science and Engineering.

Professor Rampersad is leading a number of major defence research projects, including one to develop a digital twin of a shock absorber in collaboration with manufacturer Supashock. It envisages a two-way flow of data between the physical device and its digital counterpart, allowing for preventive maintenance.

She is also involved in the development of the university’s Factory of the Future at the Tonsley Innovation District – the site of the former Mitsubishi factory – where the end goal is to create 4000 jobs over five years, with a focus on defence.

One of the goals of the facility is to reduce the risk of testing new processes. “Participating businesses can already test the feasibility of new and advanced manufacturing technologies from a technical perspective, and gauge end-user responses through research activity, testing, trial and evaluation,” Professor Rampersad says. “This approach seeks to optimise human and technology performance, so that businesses can easily apply successful innovations to production processes at their own manufacturing site.”

The site will also provide a conduit for university researchers and industry to work together, something Australia has traditionally failed to do well.

Professor Rampersad says while Australia does have high labour costs, countries such as Germany show this is not necessarily an insurmountable barrier.

“In Germany … they have been able to use advanced robotics in car manufacturing and have actually seen an increase in the size of the automotive workforce,” she says. “Boosting the number of manufacturers involved in innovative activities is crucial for Australia to achieve sustainable, high-value manufacturing practices at a scale necessary to meet future economic, societal and ecological responsibilities.”

On the skills development front, the university offers a diploma of digital technologies focused on robotics and advanced manufacturing. Degree apprenticeships, common in the UK, are also something Flinders University is now delivering in mechanical engineering.

Professor Rampersad says the latest pandemic was a litmus test for the nation’s preparedness for the future, and it found us wanting. “We saw our vulnerabilities in the Covid-19 period,” she says, “where our weaknesses in manufacturing led to supply chain vulnerabilities impacting nearly every aspect of our economy, from construction materials impacting the housing crisis to pharmaceutical manufacturing [causing] a delay in vaccines at the start of pandemic.”

The government’s advanced manufacturing report recommends the creation of a federal national advanced manufacturing commissioner, as well as the establishment of a series of “significant government-owned advanced manufacturing common user facilities in strategic locations across Australia”. To date, neither recommendation has come to pass, and many other recommendations are arguably fairly broad motherhood statements. The opportunity is, once again, ours to lose.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout