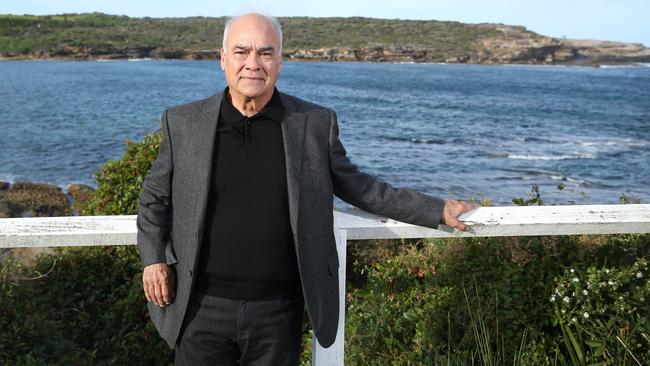

A sense of loss: Gregg opens up about his lost years

The former high-flying executive was found to have broken corporate laws twice. It killed his career, marriage and reputation. Then the convictions were overturned.

He was the numbers man for some of the country’s most prominent companies. But Peter Gregg had little idea that his signature on a minor steel contract – as the then chief financial officer at construction giant Leighton – would result in the death of his career, marriage and reputation.

That was 2011, and the move set off a series of events – catastrophic for Gregg – that saw him pursued by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission and eventually found to have broken the law twice. For the corporate regulator it was an “important decision”, as officials later told Sydney’s shock jock station 2GB.

Then in a dramatic backflip, the Supreme Court overturned both convictions and referenced 23 miscarriages of justice in the regulator’s case against him. A depressed and financially gutted Gregg has been left to pick up the pieces. So, should someone be watching the watchdog?

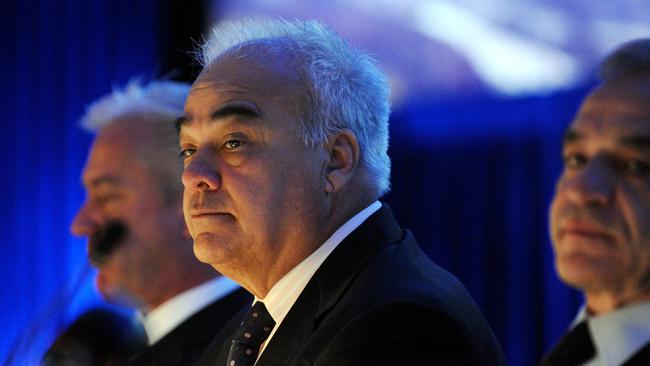

“ASIC was working on the principle of throwing a body on the tarmac,” says Rob Ferguson, former chairman of Primary Health Care, where Gregg had moved to become chief executive at the time the charges were first laid.

Ferguson, who was comparing the regulator’s actions to the hijacking of a TWA flight in 1985, where one passenger was murdered and thrown onto the tarmac to ensure authorities knew the terrorists were serious, says: “They were so vindictive … they were looking to kill him and make him feel like a pariah.” “Guilty until proven innocent is how they worked, and now he can’t seek compensation, and ASIC just moves on,” he adds.

Gregg and the Primary board, which he had led for three years after leaving Leighton, agreed he would resign because ASIC had sought criminal charges, which could, and did, drag on.

Ferguson believes ASIC was after any Leighton executive’s head on a stake because they were under pressure to respond to allegations of corruption and bribery at the construction giant, including with Monaco-based Unaoil, something that had nothing to do with Gregg.

His case involved an agreement with an Indian joint venture partner to buy and sell steel – which the Crown alleged was never genuine.

“They needed to find someone quickly, but Peter was one of the good guys – he was the victim,” says Ferguson. “It was like seeing a herd of wildebeest cross the river and watch a crocodile pick one off.”

In his only interview since his convictions were overturned, it is obvious that the proceedings and five months of wearing an ankle bracelet have left a permanent scar on Gregg.

“For me as a person that strove all the time to do the right thing for the company, for the shareholders and for the employees, it was stunning to be told I was acting fraudulently,” says Gregg. “The impact of that was that they terminated my career forever.”

And it wasn’t just his career.

Gregg’s marriage broke down amid the high profile case, and after he was convicted and placed under house arrest he was refused a request to visit his daughter who was in intensive care after suffering sudden liver failure.

“My personal life was put under quite a bit of stress,” Gregg says. “A lot of relationships suffered as well that were very important and because of the stress I was under, well that’s something I’m having to come to terms with now as well.”

Many people stood very publicly by him.

Qantas former chief Geoff Dixon, as well as former Qantas colleague, Grant Fenn, who now runs Downer EDI, were among them, as were Ron Murray from Murrays Coaches and film producer Bruce Davey.

Gregg had been Qantas CFO for eight years until missing out on the top job, which went to Alan Joyce, after the departure of Dixon. He departed for Leighton.

“The allegations were totally out of character and it was a very difficult time for Peter,” says Dixon of the years of rumours, defamatory press allegations and the two court cases. “I found him to be one of the most outstanding and honest executives I’ve ever dealt with.”

While both charges of contravening the Corporations Act were thrown out on appeal – with Chief Justice Tom Bathurst citing various errors in law – it still remains unclear why ASIC sought criminal charges in the first place on a case with no complainants and why it then pressed for a custodial sentence.

The first case started in November 2017 and finished in October 2018 with a delay getting a jury and pre-trial arguments so close to Christmas 2017. It was financially complex and heard before a judge who appeared to have difficulty with common accounting measures.

In the sentencing remarks, District Court judge Paul Lakatos accepted that the proceedings had left Gregg “a broken man who has been deprived of his sense of self worth in the latter part of his years”. Still, then ASIC commissioner John Price used it as a media opportunity declaring they would not “tolerate” any kind of corporate criminal misconduct.

Sarah Court, ASIC’s deputy chairman, declined to comment on why the regulator had pushed so hard for a custodial sentence and been so public about the first result – she was not working for the regulator at the time – but says it was important for the agency to be seen to be tough.

“The regulator has a job to do to ensure that contravening conduct is deterred,” she adds. “That’s why the regulator makes public comments; to ensure that people know the kind of conduct that regulators are concerned about and the action it will take.”

As for an apology, Court is firm.

“Initially Mr Gregg was found guilty, he was then acquitted. Obviously, that’s had a significant impact on Mr Gregg, and I don’t want to take away from that in the slightest,” Court says. “But the fact that there’s been an acquittal doesn’t mean that ASIC has not done its job, has not investigated it properly. ASIC’s done what people expect ASIC to do, which is to investigate allegations of misconduct and then either refer to the CDPP pay or file civil penalty proceedings.”

But the idea that the regulator can destroy peoples’ lives without consequence does not sit well with many.

Jones Day partner Tim L’Estrange says while regulators have a job to do, cases where executives are accused of not preventing a company’s contraventions are often nuanced.

“The repercussions for an individual are significant,” L’Estrange says of these cases, which can run, like Gregg’s for three to five years. “It will have a huge impact on the person, their family, their career and their health.”

“In the process, the individual’s reputation is likely to be trashed – and yet at the end of the day the regulator‘s case may be thrown out, settled or a modest penalty issued by a court,” says L’Estrange. “But the damage has been done.”

He believes the bar needs to be raised in these cases, which should have careful review.

Gregg is understated when he describes the whole ASIC saga as “unsatisfactory”. “From go to whoa, the time it took, the costs incurred on a financial level and on a personal level and the career impacts have been something that has made me change my life. My job was my life,” he says.

“There is always the sense of loss that you have when you’re grieving for a career that is stripped from you for a reason that it’s really hard to even logically understand now.”

The former high-flying businessman questions how ASIC is allowed to incur costs on what now appears to be a witch hunt – there are rumours it spent $20m chasing Leighton, although the regulator says the figure is far lower. “How is it that the government is allowed to just go on and without any accountability on the cost side incurred,” says Gregg.

Ferguson believes people should have lost their jobs at ASIC over the scandal. “They should be held to account,” he says. “There is a new person (at ASIC) now but this is an institutional problem not a personality problem.”