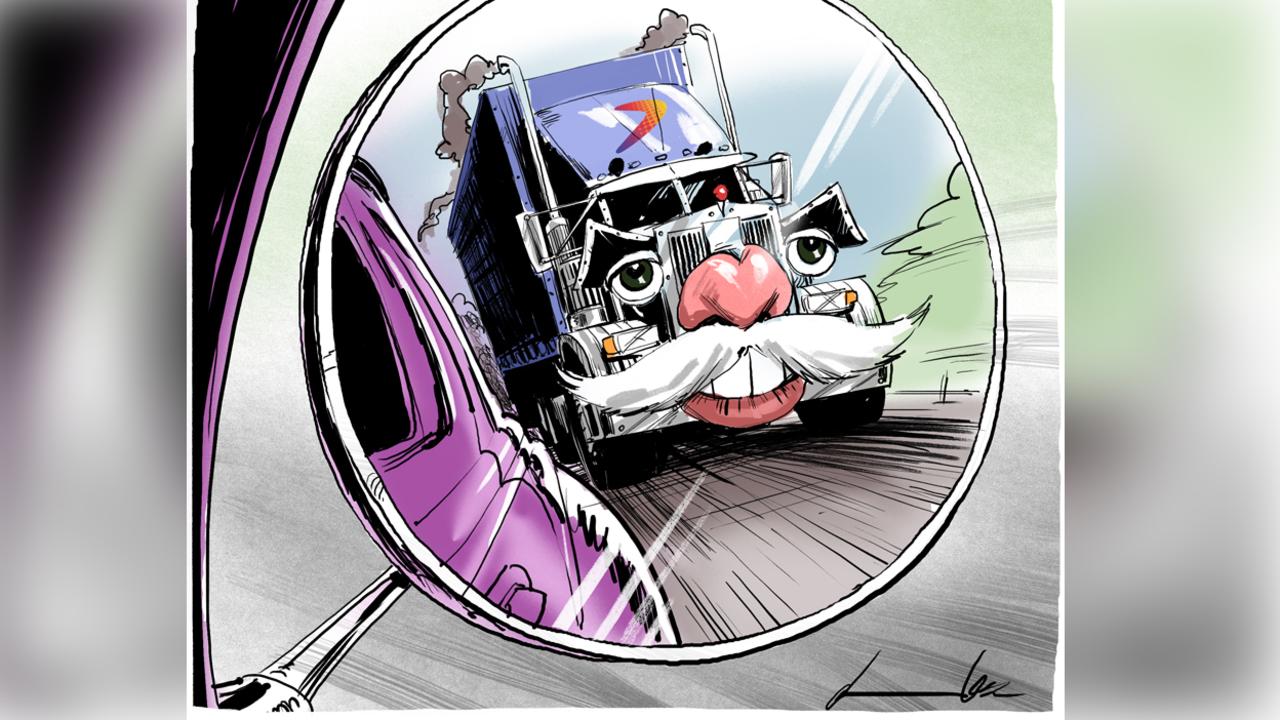

ASIC scores one against corporate high-flyer Peter Gregg

Peter Gregg’s conviction will show that even corporate high-flyers are held accountable when they break the law.

Peter Gregg was the wrong person at the wrong company at the wrong time when he joined the executive ranks of Leighton towards the end of the Wal King era in 2010, and yesterday’s conviction comes at the worst possible time for the high-profile corporate executive.

With the financial services royal commission preparing its final report, big business’s standing in the community is at a low, the federal government desperately searching for a winning issue and corporate regulators are falling over themselves in the rush to get some high profile scalps to place on top of the totem pole.

This one landed happily at the feet of ASIC boss James Shipton, with the action starting during the time of his predecessor Greg Medcraft, when Gregg stood down as chief of Primary Health Care to fight the case last year.

The message will now be sent high and wide from Prime Minister Scott Morrison down that even corporate high-flyers are held accountable when they break the law.

This is just the sort of story the government and certainly ASIC will rightly relish.

For Gregg, the scenario, from a corporate reputation, political and public relations front, could not be worse.

That is the reality facing an obviously shaken Gregg no matter what the final outcome of the court saga will be.

He will now look at a potential to appeal yesterday’s conviction on two counts of falsifying company books.

To this day the highly regarded and likeable Gregg is convinced what he did was OK and no doubt there is more information on what went on which is yet to see the light of day.

But, for ASIC, a high-profile criminal conviction could not have come at a better time after it copped a hiding in the royal commission for being too soft.

For the man himself, his many friends in corporate Australia yesterday expressed nothing but sadness and support.

This said, there will now be many others around the company who must be asking themselves questions.

The breaches occurred in 2011 in an era where executives were held accountable while today, from royal commissioner Ken Hayne down, are asking boards of directors just what they were thinking at the time.

The Leighton board at the time included some luminaries including former RBA chief Ian McFarlane. Brambles chair and long-time Westfield director Stephen Johns was chair, and Bob Humphris was also a long-time director and later chair.

Just what the then Leighton board was up to at the time is yet to be seriously examined.

Gregg came to Leighton first as a director in 2006, taking the role from his old Qantas boss Geoff Dixon at a time when the company was flying high.

He was appointed chief financial officer in October 2009 after the current Transurban boss Scott Charlton left and Gregg was reappointed to the board in December 2010.

Long-term chief Wal King ran the show for 24 years, over which time the company’s market value increased from $70 million to $11 billion, its total shareholder return was 21.8 per cent a year and revenues grew from $1.3bn to $18.6bn.

His expansion around the world through Asia and the Middle East fuelled an extraordinary expansion before the company was taken over in 2014 by Spanish-based ACS.

King’s belated departure also left a sometimes poisonous governance climate within the company with a turnover in chief executives and company and myriad executive fiefdoms being protected.

Whatever happened with Gregg, anyone who has filled the post of chief financial officer will tell you it’s one of the most high- pressure jobs in a company.

Gregg did it with aplomb for eight years at Qantas, where he played a strategy role while also forming close bonds with the late financial guru David Coe who was an integral part of the failed corporate buyout of the airline in 2007. He has maintained a strong relationship with former boss Geoff Dixon.

Gregg finally achieved his ambition to run a company when he was appointed as chief executive of Primary in 2015.

Sims’s ports case

ACCC boss Rod Sims is conceptually 100 per cent correct in the logic of his case against NSW Ports but in practical terms his law case will be a struggle.

Don’t tell Port of Newcastle this because it was out banging the drums about the economic boon to the state if it was able to ramp up its container handling.

It’s spruiking would have more credibility if its owners knew nothing about the Port Botany terms when they acquired the asset.

They knew exactly what they were buying, which was effectively a coal terminal monopoly with, at the time, unfettered rights to charge coal companies like a wounded bull.

They knew the restrictions on containers and there is nothing to stop them expanding — it just costs them more money, which can be paid out of the monopoly rent on the coal charges.

The logic in the ACCC case is governments must think about the long-term competitive impact of their asset sales and not just the immediate windfalls.

That’s a smart suggestion not often followed by greedy politicians from John Howard down.

But Rod Sims is bound by the terms of his legislation, which is presumably why he didn’t block Transurban’s bid for WestConnex when the monopoly toll road operator already controlled seven of Sydney’s nine toll roads.

The NSW Ports case is presumably based on the fact the Port of Newcastle must pay a penalty per container for each unit which lands in its port over a set threshold.

Ironically, the terms were reputedly inserted at the behest of one-time Newcastle manager, Hastings, which was a rival bidder for Botany.

Hastings, of course, is no longer a player in the Port of Newcastle, which is managed by Macquarie and owned by China Merchants and The Infrastructure Fund.

Botany was sold in 2013 for $5 billion, Newcastle in 2014 for $1.8bn and Melbourne in 2016 for $11bn.

Melbourne is the biggest container port in Australia and its sale was done in textbook terms with full consultation with the ACCC which means the government has more control over port pricing and the lease terms say the government can’t subsidise a rival port in 15 years.

The NSW monopoly at Botany and Kembla lasts for 99 years.

At the time of its sale, Botany was running at about one-third capacity and the NSW government figured when it hit capacity the next port would be Kembla, which suited the rail requirements around the Moorebank intermodal terminal. If the then NSW premier Mike Baird made a mistake it was in selling Kembla with Botany and not in separate lots and without control on pricing.

Newcastle, of course, has run into its own competition issues, which means Glencore has won a pricing ruling requiring ACCC arbitration on any disputes.

This shows the ACCC is taking with one hand while the law is giving with another.

As a regulator Sims understands the importance of the demonstration impact and his port action against IFM Investors and AustralianSuper will ring the warning bell on all government asset sales. Certainly buyers will be asking the questions.

The real perpetrator of any wrong doing, the NSW government, is cleared through Crown immunity.

The ACCC must prove the NSW government deal had a substantial impact on competition, which is no easy task given Newcastle can trade containers all it likes if it manages to get shipping companies to actually stop in the port, and if it wasn’t making out like a bandit on its coal charges. The dispute will now head to court.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout