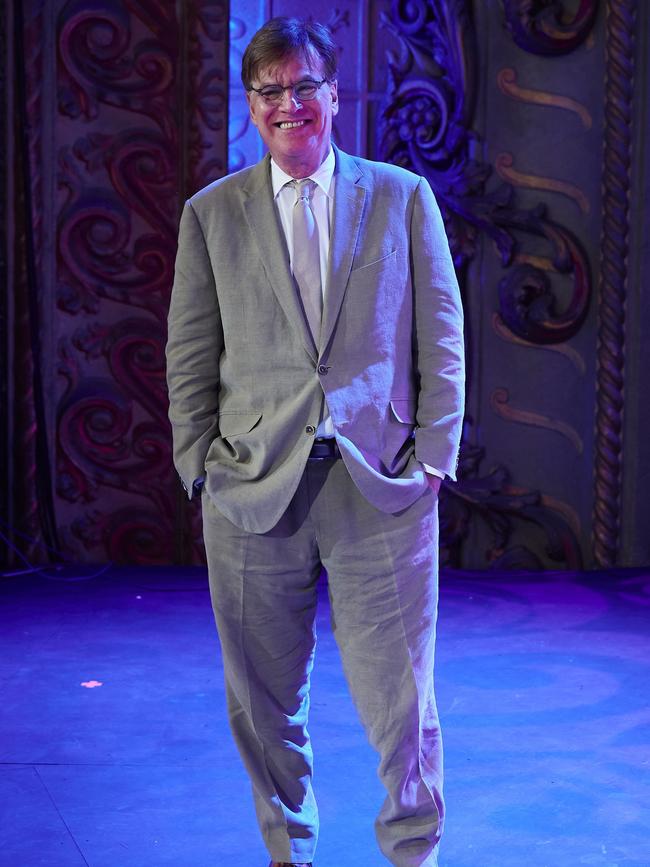

Vivid 2022: Aaron Sorkin has writer’s block

Aaron Sorkin, the prolific - and wordy - playwright and screenwriter, says the world still needs heroes that don’t wear capes.

For Aaron Sorkin, if there is a unifying theme that runs through his plays, television shows and feature films, it is that the future can always be brighter, that there are reasons to be hopeful and the better angels of human nature should win out in the end.

“The common thread, if you ask my friends, would be an idealism, a romanticism and an optimism,” Sorkin, 61, tells The Australian during his only media interview while in Australia for Vivid Sydney. “Even when there really is no reason to be optimistic, I tend to write that way.”

Sorkin’s writing for the stage, television and cinema – including A Few Good Men, Sports Night, The West Wing, The Social Network, Steve Jobs, The Trial of the Chicago 7 and Being the Ricardos – has won him critical acclaim along with an Oscar, Golden Globes, a BAFTA and several Emmys.

The writing, however, has not always come easily. Sorkin, who grew up in New York, performed in high school plays, studied drama at university and worked a series of jobs – small acting parts, bartender, driver – while writing plays. His first big break was A Few Good Men (1992) for the stage and then the screen.

The moment that prompted him to become a screenwriter, and more recently a director, came when his parents took him to see Man of La Mancha on Broadway at age six.

“It was the first show of any kind that I saw and it cast a spell on me,” Sorkin says. “Not only did that theatre become a cathedral but the story itself of Don Quixote would just be this lifelong injection of idealism and romanticism.”

That idealism and romanticism was writ large in the film The American President (1995) and the series The West Wing (1999-2003). They sought to elevate and uplift politics as an honourable profession, where decent people are motivated to do good things while being tested and have setbacks but never lose sight of what drives them.

“In popular culture, our leaders by and large have been portrayed either as Machiavellian or as dolts – it’s either House of Cards or it’s Veep – and so I wondered why there can’t be a show where our political leaders are every bit as competent and committed as the doctors and nurses on a hospital show or the police detectives on a cop show, or the lawyers are on a legal drama, and so that is what I did,” Sorkin says.

The American President mixed romance with drama and light comedy as widower and parent President Andrew Shepherd (Michael Douglas) grappled with gun control and climate change while falling in love with lobbyist Sydney Ellen Wade (Annette Bening). It illuminated the struggle between political principle and pragmatism and was, above all, a film about character and leadership.

That film became the springboard for The West Wing. Martin Sheen, who played chief of staff AJ MacInerney, returned for the series as president Josiah Bartlet. (Sorkin has a stable of actors who have appeared in multiple productions.) The series, focused on the president’s staff and family, honed a Sorkin trademark: fast-paced dialogue as characters walk, and long explanatory monologues.

The West Wing won a slew of awards and critical praise for its highbrow, intelligent storylines that spotlighted the complex world of politics with panache but was criticised for being lofty, unrealistic and mawkish. Yet it continues to strike a chord with new generations because it affirms the virtue of public service.

Given the political polarisation and deep divisions in the US, could a hopeful show like The West Wing be made today?

“I would write it the exact same way,” Sorkin insists. “We’ve never, certainly not in my lifetime, and I don’t think in the last century, been as divided in the US as we are now. I can’t give you a reason to be optimistic. But I think if I was writing that show, I would write it optimistically and romantically and idealistically. I would try to create a world that we would want to live in as opposed to the one that we do live in. It’s basically writing heroes who don’t wear capes.”

The West Wing cast reunited for a get out and vote benefit ahead of the last presidential election and staged an episode from season three (Hartsfield’s Landing) which was shown on HBO Max. But will we get a newly scripted reunion on television?

“We have West Wing reunions in a restaurant,” Sorkin jokes. “If I could think of a reason why these people would get together without it seeming silly, then I would do it just for the chance to revisit those characters and just for the chance to work with those people again.”

So, maybe.

Perhaps no television series has inspired more people to go into public service than The West Wing.

Generations of advisers see themselves as Leo (John Spencer), Josh (Bradley Whitford), Sam (Rob Lowe), Toby (Richard Schiff), CJ (Allison Janney), Will (Joshua Malina), Charlie (Dule Hill) or Donna (Janel Moloney).

But Sorkin says he does not set out to influence an audience or change how politicians, media, military or corporations behave. He explains that trying to achieve social, political or economic change has nothing to do with the rules for writing drama. His fidelity is to storytelling.

“Before it can be influential, before it can be relevant, it has to be good,” he says. “It has to be able to stand on its own as a piece of entertainment – something that you watch with a bucket of popcorn in your lap … I love telling a story, so I am thinking about that. And if I do it well enough, it has a chance – just a chance – to reverberate beyond the screen, beyond the stage, beyond your television set.”

Sports Night (1998-200), Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip (2006-07) and The Newsroom (2012-14) were fictional dramas, whereas Charlie Wilson’s War (2007), Moneyball (2011), Molly’s Game (2017), The Trial of the Chicago 7 (2020) and Being the Ricardos (2021) were based on real people and events.

Non-fiction requires different research and writing but the essential elements of storytelling remain the same. Sorkin explains there are facts in non-fiction stories that must be adhered to but dramatic licence allows aspects of the story to be changed if they speak to a larger truth about what happened and why.

“There is a difference between art and journalism and there’s a difference between truth and accuracy,” he says. “It’s the difference between a photograph and a painting, and even when I’m writing non-fiction, I’m doing a painting.”

Sorkin’s stories are character-driven. It is easy to admire Jeff Daniels as Will McAvoy in The Newsroom, Tom Hanks as Charlie Wilson or Sheen as president Bartlet. Although it is harder to like Jack Nicholson’s Colonel Jessup in A Few Good Men, Mark Zuckerberg in The Social Network (2010) or the Apple co-founder in Steve Jobs (2015), the audience must empathise with and understand them.

“You don’t tell the audience who a character is, you show the audience what a character wants,” he says. “Drama is intention and obstacle: somebody wants something, but something is standing in the way of them getting it. The tactics that a protagonist uses to overcome an obstacle – that’s going to colour-in your character.

“When you are dealing with someone like Mark Zuckerberg or for that matter Steve Jobs, who is not that easy to like … you as the writer can’t judge the character … you have to write that character as if they are making their case to God as to why they should be allowed into heaven.”

Sorkin describes his writing process as “a lot of climbing the walls”. He is a workaholic. He researches extensively, reads dialogue out loud, sits and stands and paces, writes in bursts of energy and brilliance, and often turns in pages late. “I don’t think it is going to inspire anyone,” Sorkin says.

Later this year, Sorkin’s play, Camelot, based on the 1960 musical, opens on Broadway. It follows another story he adapted for the stage, To Kill a Mockingbird, which ran on Broadway and London’s West End. But now he is dealing with an agonising case of writer’s block.

“For the first time in five or six years, I don’t know what I’m doing next,” Sorkin says. “When I don’t have an idea, it’s impossible for me to imagine ever having an idea. So, that is where I am right now. I’m reading a lot of books, magazine articles, newspaper articles, hoping that there’s a spark somewhere where I feel like I have a chance of writing a good movie, and that’s all I am looking for.”

It is a Sorkin trademark to end his shows with answers, wrapping things up, to make things final before fading to black. In four of his shows – Sports Night, The West Wing, Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip and The Newsroom – a final episode in his run as writer was titled: “What Kind of Day Has It Been?” So, I ask: what kind of day has it been?

“You know what kind of day it has been,” Sorkin laughs. “I get to earn a living doing exactly what I love doing and I don’t know how many people there are who can say that the best part of their day is when they go to their job. I got that life. There isn’t a single day that I take that for granted.”

Aaron Sorkin was a guest of Vivid Sydney’s festival of light, music and ideas.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout