Weimar breaks down the barriers

ARTISTS of all kinds are in concert on a Berlin theme.

JACQUELINE Strecker was in a line to buy tickets for a cabaret performance at the 2008 Sydney Festival when she had an idea.

The Art Gallery of NSW curator of special exhibitions had just returned from Germany where she had begun securing loans from museums for The Mad Square, an exhibition of German modernism she was planning.

"I had a lot of time to think in the queue," Strecker says. "I had the very big but simple idea of not only looking at the visual arts of this period in Germany, but also looking at the performing arts."

The idea was simple: the theatre, cabaret and music of Weimar Germany are, to the general public, possibly better known than the art of the likes of Max Beckmann and Otto Dix. But the idea was big in the sense that it would involve other cultural institutions around the city, a concept rarely seen these days in the arts world.

As Melbourne Symphony Orchestra managing director Matthew VanBesien explains: "To some degree, arts organisations are much more institutionalised now in a way that is not always conducive to the bare-bones creative mindset."

VanBesien believes the later years of the 20th century saw a "great separation" between different art forms that was not apparent at the start of the century.

The Art Gallery of NSW contacted Cate Blanchett and Andrew Upton, who had recently taken the reins as artistic directors of the Sydney Theatre Company. Strecker showed them images and ran through her concept for the exhibition, as well as the collaborations she was hoping for.

Their response was positive, with Upton noting that their plans for the STC had always included working across art forms. He says it is fertile ground for audiences and the companies involved.

"It's a great thing to do because it gives you a chance to share and build up your audience," Upton says. "But it also opens up the dialogue between the different forms, showing the ways each one deals with similar themes."

After getting a positive response from the STC, Strecker stepped up her efforts with other companies. She was strategic, making sure the companies she contacted were not in competition with one another (which is why Belvoir didn't get a call).

"There were those kinds of sensitivities to consider," she says, noting that competition can also relate to sponsors, with two arts companies sponsored, for instance, by competing airlines. "It wasn't an issue with this, luckily, but it could happen."

Another complication, says Upton, centres on funding bodies set up to ensure each art form is "a separate entity, unable to cross-fertilise".

Strecker also kept her approach to a "fairly tight group, to keep it a focused series of events".

"It can all start to lose its impact if it gets too big," she says.

Meetings with Sydney Opera House management directed her towards Opera Australia and Sydney Symphony. She also got in touch with smaller venues around town such as art dealer Rex Irwin and the German cultural organisation, the Goethe-Institut.

All the organisations Strecker approached were receptive in theory to the idea of Berlin Sydney, as it is known. Strecker says it took persistence to bring everyone together.

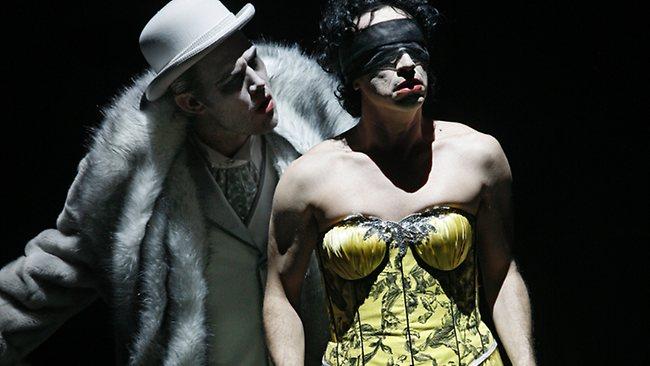

Participating companies were given full programming autonomy. So Berlin Sydney came to include the STC's The Threepenny Opera, opening on September 3, Sydney Symphony's live score to accompany Fritz Lang's Metropolis, and exhibitions at locations including the Museum of Sydney, Goethe-Institut, Dominik Mersch Gallery and the Rex Irwin.

Shortly before the Berlin Sydney brochure went to print, another Sydney venue, the Seymour Centre, contacted Strecker to say it was doing a cabaret set in Berlin and wanted to be included as well.

While VanBesien believes the late 20th century was a time of separation between art forms, Blanchett says things are changing. "Companies are empire building less and collaborating more. It may be a generational thing."

The STC is talking to companies such as the Australian Chamber Orchestra, Sydney Dance Company and Force Majeure about possible collaborations. Even the American-born VanBesien, who arrived in Melbourne 18 months ago, says the MSO has collaborated more with an external company - the National Gallery of Victoria - than he encountered in his five years with the Houston Symphony.

"It wasn't that we didn't have a relationship with the major arts museums in Houston," he says. "But in some ways, because of the competitive nature of the philanthropic landscape there, it makes it harder in certain US markets to collaborate."

VanBesien says in Australia he has found a "tremendous willingness" among companies to discuss ways to help each other and to create projects that wouldn't be possible alone. He's excited about the prospect of "a concert-type presentation with one of the major theatre companies in Australia" next year, and by initial conversations with Melbourne's Immigration Museum and the Australian Centre for the Moving Image.

Geography alone can play a role in collaborations.

Art Gallery of South Australia director Nick Mitzevich says the positioning of the gallery, State Library of South Australia and the South Australian Museum, within steps of each other on Adelaide's North Terrace, allows for "regular dialogue" on issues ranging from administration to philanthropy, as well as well as artistic discussions.

And in Brisbane, the new cultural precinct is staging the largest exhibition of Torres Strait Islands culture, a collaboration between the Queensland Museum, the State Library of Queensland, the Gallery of Modern Art and Queensland Performing Arts Centre. And as with Berlin Sydney, it came down to one man to bring it all together.

Tom Mosby, executive manager of indigenous research and projects at the State Library, came up with the idea when talking to his partner, Queensland Art Gallery director Tony Ellwood, about the excellent TSI holdings in each of the precinct's institutions.

"You're cutting through layers of bureaucracy when you've got two people who can bring something to the table rather quickly," Ellwood says.

He says visitors can follow a chronological flow between the buildings, starting at the museum's 19th century artefacts and finishing with the gallery's contemporary works, "as if it was meant to happen".

The danger, Ellwood says, is if the strategy is forced, lacking the "sincere will" of each partner involved.

There are limits to collaborations. Art galleries have strong after-hours programs - films, talks, music and so on - and these, rather than joining forces with other organisations, can be a priority, he says.

"We would traditionally invest more time and resources to onsite programming," he says, "because we have to drive an audience for more ambitious shows directly into our venue. We need enough activity to get people into the building to purchase a ticket, and then add layers to make it a more pleasurable experience."

In Adelaide, Mitzevich has organised for the Adelaide Film Festival festival to program a series of contemporary British films inside the gallery to coincide with the exhibition British Art Now from London's Saatchi Gallery. It opens this weekend and runs until October 1.

"The challenge for us all is production time," he says. "Sometimes a project lands on your desk and you may want to work with a theatre company or orchestra, but you can't expect them to drop their artistic program. A lot of things need to come together, and production time is critical."

The gallery secured the British exhibition six months ago, and the film festival was well placed to act quickly.

"There's no way we could have worked with an orchestra or opera company," Mitzevich says. "Even if we had all the best intentions, sometimes the form and lead time get in the way. But when all the planets align, it's a beautiful thing."

The Mad Square opens today at the Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney, and runs until November 6.