Uighur artist Aniwar Mamat’s Australian show: a fascination with borderlands

Aniwar Mamat’s work is inspired by traditional felt makers in China’s Xinjiang province as well as by the corrugated iron sheets outside his window during Beijing’s Covid lockdown.

Uighur artist Aniwar Mamat was born and raised in western China’s Xinjiang region, home to many of the mostly Muslim minority. When he was 18, in 1980, he had a rare introduction to European art because his mother worked in the state-run library in Urumqi and he had access to the books there.

So, while other Chinese artists were working in a very closed environment with strict censorship controls, Mamat pored over Western art books unavailable to them, including works by Russian artists such as Kazimir Malevich and Wassily Kandinsky.

This unique background stood him in good stead as his own career developed when he moved east to study art at the Tianjin Academy of Fine Arts.

His passion for working in carpet, one of the products of Xinjiang, drew him back to Urumqi in 1981 and the Xinjiang Carpet Research Centre, where he spent four years studying the unique carpet patterns of the region.

In the mid-1980s, as China was opening up to the West, he moved to Beijing to study painting at the College of Fine Arts at Minzu University.

He became a teacher at the Beijing School of Arts and Design, where he met the then Australian ambassador to China Geoff Raby, who was a fan of Mamat’s brother, Askar, and his Grey Wolf Band.

Raby was so excited about the group that he took holidays to bring Askar’s band to play in Australia at the Darwin Music show in 2009, which is when Aniwar Mamat made his first trip to the country.

An enthusiastic collector of contemporary Chinese art since first arriving in Beijing as a young diplomat in 1986 and again when he returned as ambassador in 2007, Raby bought some of Mamat’s works.

In 2015 he took a visiting representative from the National Gallery of Victoria to see the artist’s studio in Beijing and the gallery bought three works.

Mamat, whose status as a contemporary artist in Beijing has only grown over the years, has made his second trip to Australia for the opening of his first exhibition here, curated by Raby at Vermilion Art in Sydney. Raby says it is the first exhibition of contemporary Uighur art in Australia.

Titled Borderlands, it reflects both Mamat’s origins in Xinjiang, (his hometown of Kargilik is near the ancient town of Kashgar, key stopping-off point between China and Europe along the old Silk Road), and the combination of the influences from the east and West in his work.

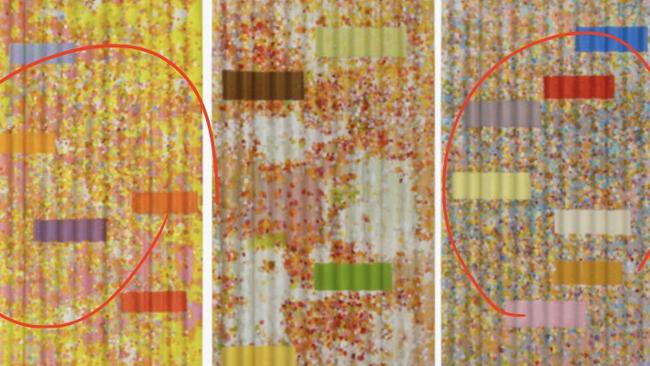

The exhibition covers three phases of his practice. First, there are the brightly coloured traditional works in acrylic and oil on canvas and board, featuring backgrounds sprinkled with dots overlaid by geometric shapes; second, the woollen felt pieces made in Kargilik and Yerkan (also in Xinjiang), that also feature his iconic similar geometric shapes.

The third stage of his work was forged by the isolation of Covid where he was in lockdown in Beijing from 2020, confined to his home, which was surrounded by walls of corrugated metal sheets.

Shopping for materials online, he became interested in tempered glass panels corrugated with the same forms as the walls he was seeing every day during his period of enforced isolation.

These were the basis for his more recent works of colourful dots and geometric shapes painted on to light blue fibreglass, in a series called Sun, Rain, Moving Light.

Mamat says the new medium has taken his work to a new level.

“As I painted on these corrugated surfaces, I quickly discovered the visual instability and extraordinary dynamism of the images they produced,” he tells The Australian.

“This experimentation further highlighted and enriched the independence of my painterly language.”

As for his painting, Mamat says “the uncertain language of boundaries is the core of my exploration”.

“The exhibition title, Borderlands, perfectly encapsulates my pursuit of dynamism in painting and my open-minded understanding of borders and boundaries.”

“Looking back, I realise that the architectural forms and geometric patterns found in traditional textiles from my upbringing have continuously shaped and accompanied the spatial structure of my paintings.”

Raby says: “Although formally trained in the East, in Tianjin and Beijing, Aniwar’s work embraces all the influences he absorbed growing up in the far west.”

“One is first struck by the vividness of the work. The intensity of his colours brings to mind the clarity of light in the desert landscapes of Xinjiang and the brilliance of Persian architecture, as can be seen in the great mosques of Samarkand.”

Raby argues that Mamat’s geometric patterns conjure up the spirit of Islamic art and design “but in Aniwar’s hands, rigid form gives way to freedom of expression”.

Melbourne-based curator Damian Smith says Mamat’s work reflects the influence of early Soviet, or Russian, constructivism, inspired by the works of Kandinsky and Malevich that Mamat saw in the library in Urumqi. He argues that presence is particularly prominent in Mamat’s works in felt: pieces made from local wool and pressed layer upon many layers, are coloured by stencils at each stage.

While Mamat comes from Xinjiang, with its rich history of Islamic minorities, Smith points out that he brings his own European influences to his work.

“In place of arabesques and curlicues, one sees the hard line of modernity imposed on to softer surfaces and backgrounds,” he says.

“Kazimir Malevich’s infamous ‘black square’ has found its way to Xinjiang.”

Smith sees Mamat’s latest pieces on fibreglass as featuring “transient horizontal lozenges gliding across the visual plain (which) bring to light reveries, dalliances and peregrinations within the wide open spaces”.

The exhibition is taking place against the backdrop of tensions between China and the US, and critical attention given to the Chinese treatment of minorities in the region including the Uighurs.

Mamat’s work is deliberately abstract and does not address any political issues. He also rejects requests to provide any neat stories behind his works, arguing that they are open to interpretation, and wanting each viewer to make up their own mind.

As Smith says: “Politics is not the only voice in the room. Aniwar’s is a very human story and what better way to represent Uighur culture than his modern, outward looking, sophisticated, nuanced work.”

Borderlands will be at Vermilion Art in Sydney from April 29 to May 31.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout