Tibetans on show at Red Gate but other Beijing spaces facing shut down

Brian Wallace is on the move again in Beijing as his studio space faces demolition to make way for an apartment block.

Brian Wallace is a veteran of the ups and downs of the Chinese art world. The Australian gallerist is excited about hosting a new exhibition of young Tibetan artists at his Red Gate Gallery, part of Beijing’s gritty 798 urban art district. But he’s disappointed that a studio space he has had for 17 years on the city’s outskirts is about to make way for apartment blocks.

Wallace has been running the Red Gate Gallery in various locations in Beijing since 1991. He is hosting Tibet Now, showing works by 10 artists. It is his first exhibition of Tibetan artists in 10 years. At his previous exhibition of Tibetan art, Return to Lhasa, in 2008, some young Tibetan attendees were trailed by police.

The Tibetan art scene has since developed significantly and some artists have acquired substantial international followings.

Looking at the works in his studio, tucked away in a corner of the busy former Beijing factory zone, Wallace says each artist offers a unique vision. “You could do a wonderful solo show with each of the artists,” he says. “But by bringing them together it reflects the diversity of their practice.”

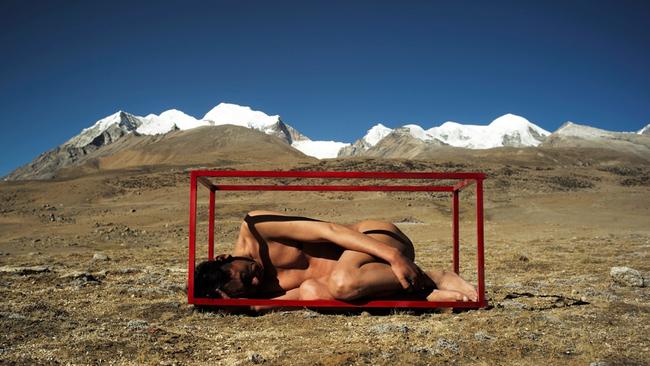

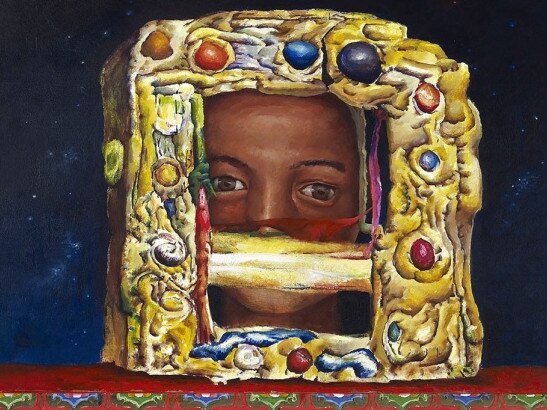

One of the artists, Norbu Tsering, is displaying a photograph of himself naked in a box against the backdrop of the barren Tibetan landscape with snow-covered mountains. The work is called Sky Burial. A work by another artist, Tsering Nyandak, depicts a Tibetan girl looking through a window that resembles a painted frame, with the bars of the window across her mouth. This is Starry Starry Night.

“There are a whole range of topics in the works, ranging from the environment to tradition, consumerism and globalisation,” Wallace says. “But a theme I am getting coming through from some of the work is a feeling of isolation.”

Some of the works show the harshness of agrarian life in Tibet. The influence of Buddhism also comes through. One artist, Karma Tenzin, shows a Buddhist figure made of coloured buttons that seem to fly around in the background like butterflies. Another, Kalsang Norbu, has a series of Buddhist figures in the middle of butterfly wings.

Wallace recalls the tension a decade ago when he realised some young Tibetans showing work at his gallery were being followed.

“Nothing happened but the security police presence was sort of an acknowledgment that everything was not that free and easy,” he recalls.

He believes Chinese authorities are starting to recognise the importance of developing a thriving cultural scene, particularly in the country’s capital. But the artists also know how to navigate changing official sensitivities.

Wallace has just learned that the studio space he organised 17 years ago for a residency program for young artists to spend time in Beijing is about to be demolished.

As many as 60 young artists a year come through his residency program, staying for a few weeks in an apartment he has organised, and gaining access to the studio in outer Beijing.

But as land prices skyrocket in the Chinese capital, the old factory areas that have been such a haven for its artists — including one that hosted an Ai Weiwei studio — are being demolished to make way for urban development.

“The bulldozers are almost at the door,” Wallace says. “The studio is going to be demolished. We have just been given formal notice. We knew it might happen, but it has come up a bit faster than expected.”

He is scrambling to organise other apartments with big work spaces for the next wave of artists coming through the residency program. While the Red Gate Gallery is his shopfront, Wallace’s residency program is one of his great passions.

Seventeen years ago, he started helping Australian artists who came to Beijing on programs sponsored by Asialink. He worked with friends to find them apartments, then studio spaces. It grew into a more active organised program of residences.

“We have had about 1000 artists coming through the program,” he says. “It used to be all Australian but now we get people from all over the world. Australia only represents about 20 per cent of the artists we see now.”

Born in the mid north coast NSW town of Taree, Wallace first came to China as a backpacker in 1984 and ended up, after a few trips back to Australia, making Beijing his home.

Since then he has had a box seat in the evolution of contemporary art in China. As a student in Beijing in the 1980s, he made friends with many Chinese artists. At the time there were no galleries, so Wallace and his friends would organise spaces for artists to hold exhibitions.

After he decided to remain in Beijing, he opened the Red Gate Gallery in 1991. It has led him to become a mentor to many foreign and Chinese artists who pass through the Chinese capital, the heart of the country’s arts scene.

After 27 years in the capital, Wallace has strong ties with a growing number of young Chinese artists making very different statements to the early generation of Chinese artists who emerged when China was beginning to enjoy increasing prosperity.

“Back in the 80s, when things were opening up, it was the first time that Chinese artists could get a lot of information about the international scene, rather than just reading about it in a poorly reproduced book,” Wallace says.

“They absorbed everything from overseas. They tried everything, they regurgitated it. They absorbed all of it, but then they moved on to become more confident in their own contemporary Chinese practice.

“Many of that generation had a very different life experience to these young Chinese artists in the system now. Their families would have been affected by the Cultural Revolution, so their life experiences were very different.”

Wallace says many of the younger generation of Chinese artists may be more technically skilled, “but their comments on life are far more shallow”.

Younger Chinese artists, he says, have ridden the boom in the popularity of Chinese art that has swept the Western world in the past two decades.

“Everything has just got better and better for them,” he says.

Even so, he describes Tibetan artists and other Chinese artists shown in his gallery as part of a new generation that has something to say.

“There are a couple of artists we know who we can see are going to be important artists in 20 years time because they are starting out in such a strong way,” Wallace says.

“They are talking about newer but still important issues — issues of what is happening today — which are very different to those of the older generation of Chinese artists.”

During his time in Beijing, Wallace also has encountered an increasing number of Chinese-born artists who migrated to Australia, then returned to China, or who move regularly between the two countries.

One of those is Sydney-based Guan Wei, whose work is showing in Beijing.

“He has got the best of both worlds,” Wallace says. “He can be up here in the Chinese art scene, but he has got very good dealers in Australia.”

Wallace says he has encountered surprisingly few problems with Chinese authorities during his years in Beijing. There was one case, ahead of the 2008 Beijing Olympics, when he had a studio closer to the city and a local official visited to see whether the venue could be used during the Games.

At the time, Wallace was putting up paintings that included a reference to the sensitive issue of the Tiananmen Square demonstrations of 1989.

“We were hanging a show which was quite tough and involved some work about Tiananmen Square,” he recalls. “He told me that the paintings had to come down. He said he would lose his job if the exhibition went ahead. He was quite civil but firm. So we had to take them down.

“But it was the day before the opening and all the invitations were already sent out. So we went ahead with the party with spotlights on the blank walls.”

One of his latest challenges is raising funds for residencies for Chinese artists to spend time overseas, including in Australia. He uses crowd-funding to gather resources for overseas trips.

Wallace says the boom in Chinese art reached a peak in 2008, when almost anything from the country was selling. The market has since come off the boil as a result of the global economic slowdown and a crackdown against corruption in China.

“Times are becoming tougher,” he says. “A lot of artists aren’t selling like artists did 10 or 15 years ago, when the market was booming. And for the first time they are being faced with evictions. It is really challenging for them.

“A lot of kids went into the academies which provided commercial training. They said, ‘Art is hot. We are going to make a lot of money out of it.’ But that has gone away.”

And now they are losing their studio spaces as the bulldozers move in. “It is getting back to artists who are really artists,” he says. “Who see art as their calling, as the life they have chosen to have.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout