Heaven and earth in Chinese art arrives in Sydney from Taiwan

Artworks fit for an emperor come to Sydney as part of the Heaven and earth in Chinese art exhibition.

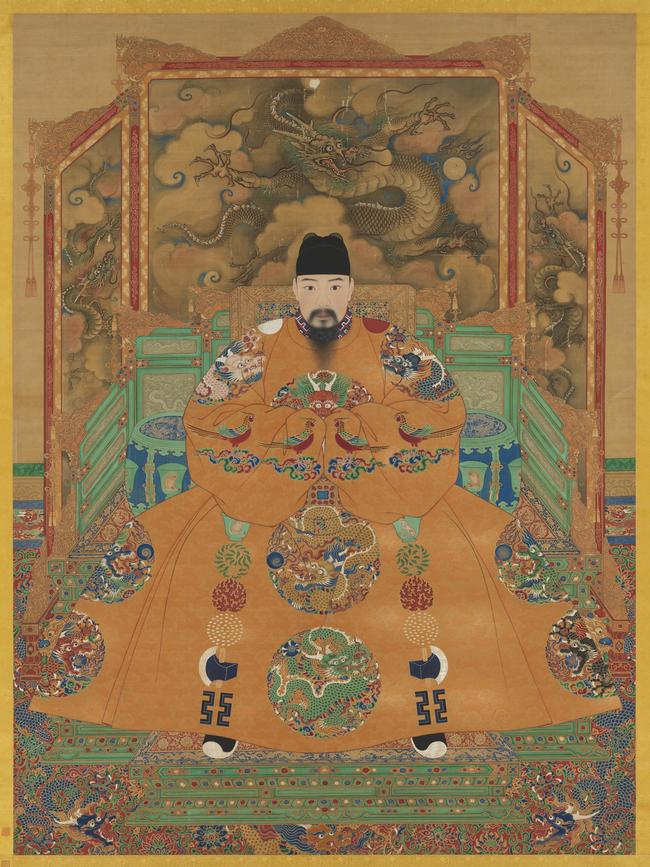

For the many connoisseurs and enthusiasts of Chinese culture, the National Palace Museum in Taipei stands supreme. This is the museum that houses the greatest works commissioned and received by the Chinese emperors, gathered over the millennia.

The genesis of its collection — about 700,000 pieces, the best shown on rotation in the museum in wooded hills on the edge of the city, some of which form part of a new show at the Art Gallery of NSW — is a remarkable story in itself.

There are two Palace Museums today. The original was founded in 1925 in Beijing after valuable items began slipping out of the Forbidden City there following the deposing of the last emperor, Pu Yi. Scholars were recruited and considerable research begun.

In 1931, as the Japanese began to extend their grip on northeast China, the Kuomintang (Nationalist) government evacuated the entire collection for safety to Shanghai, then Nanjing, in about 20,000 crates. After Japan’s full-scale invasion of China began in 1937, the crates were sent off again — some by river, some by rail and road — to the mountainous inland province of Sichuan, where president Chiang Kai-shek made Chongqing his headquarters.

As the Nationalists began losing the ensuing civil war with the communists, the cream of the collection was sent in 1948 by ship, with a naval escort, to Taiwan, where a massive bomb-proof shelter was built to house the works, and a new museum to display them was opened in 1965. Most of the curators of the collection accompanied it to Taiwan.

Although this move was vilified in Mao Zedong’s time as cultural theft, the widespread destruction of China’s heritage during the Cultural Revolution — with many ancient items looted by Red Guards surreptitiously sold to foreign collectors — enabled Taiwan to claim that it had preserved the treasures from damage or theft.

Today there is a close collegiate relationship between this newer museum in Taipei and the original National Palace Museum in Beijing — which retains a similarly vast collection — with frequent exchanges of staff and scholarly analysis.

But Taiwan authorities remain guarded about the prospect of Beijing seeking the return of these celebrated treasures, which is why they insist that any country that seeks to borrow works passes legislation that offers immunity against seizure. The passage by the Australian parliament of the Protection of Cultural Objects on Loan Act in 2013 thus opened the door.

Cao Yin, AGNSW’s curator of Chinese art, herself originally from the mainland, first saw items from the Taipei collection at New York’s Metropolitan Museum in 1996, while she was studying for her PhD in Boston.

“We all knew about the masterworks and treasures in Taiwan,” she says. “As a curator of Chinese art, it’s your ultimate dream to work with them.” Chinese citizens such as Cao, though, were not allowed to visit until 2008, in tour groups, and after 2011 on self-planned visits.

A few years after the protective legislation was passed, the Taipei museum approached Suhanya Raffel, former deputy director of AGNSW and now executive director of the M+ museum in Hong Kong. Cao, the gallery’s China expert, did not hesitate when asked her opinion: “I immediately said yes.”

It is remarkable, she says, how many of these great works have survived through China’s devastating 20th-century wars: “Chinese people were determined to save their heritage.”

Cao spent two weeks in Taipei almost two years ago discussing the selection of artworks. The museum proposed two themes, from which she chose that of heaven and earth — “a core Chinese philosophical idea”, she says, “in which I am a true believer”.

About 1100 years ago the Confucian scholar Zhang Zai wrote in an essay: “Heaven is my father and Earth is my mother, and even such a small creature as I finds a small place in their midst.”

Cao put up her wish list, and was delighted with the proportion the museum approved. Heaven and earth in Chinese art is not only the first time the museum has lent works to Australia but the first time they have been anywhere south of the equator.

The number and range of objects had to fit the lower Asian gallery in Sydney. New cases have been constructed, especially for the freestanding displays.

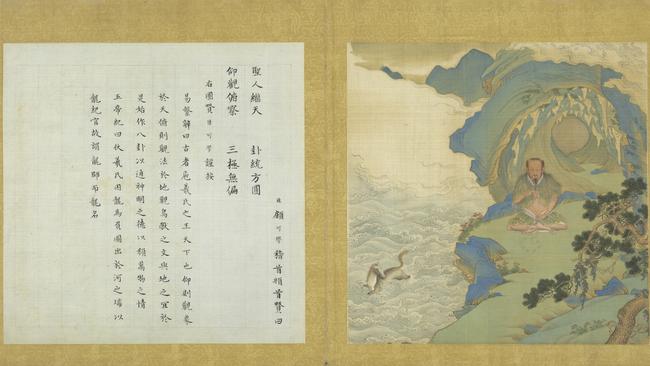

The works include paintings, calligraphy, illustrated books, bronzes, ceramics, jade and wood carvings. They have been divided into five thematic sections: Heaven and Earth, Seasons, Places, Landscape and Humanity.

They include one of the museum’s most popular pieces, which many of its millions of annual visitors — including from mainland China — queue to see: a piece of reddish jasper, smaller than the palm of a hand, carved during the Qing dynasty in the extraordinary likeness of a piece of soy-soaked braised pork.

“I didn’t expect to get it, to be honest,” Cao says of Meat-shaped stone. “It’s one of their three most popular works.”

Another celebrated piece is the olive stone carved by Ch’en Tsu-chang in 1737 into a boat, containing eight passengers, seated on chairs and eating from dishes. Beneath it are inscribed the 300-plus characters from a famous ode composed by Su Shi in 1082 that describes an excursion with friends on the Yangtze river, sailing past the site of the Battle of Red Cliffs. This ode in turn inspired many further Chinese masterworks, including what Cao describes as “one of the 10 greatest works of calligraphy in Chinese history”, which has also been lent for the show.

The exhibition in Sydney also includes priceless ceramics from the Song dynasty from a millennium ago, such as a celadon bowl in the shape of a lotus blossom, the epitome of purity.

Later works demonstrate the influence of Western perspective and techniques, including a painting of the Italian Jesuit genius Giuseppe Castiglione at work in the courts of three 18th-century Qing emperors.

While some Chinese art with which Westerners have become familiar comes from tombs, the pieces in this show “were made for the living”, Cao says — for the delight of emperors and their courts, rather than being consigned for use in the underworld.

The exhibition, she says, explores the way the artists have used diverse media to express their reflections on and responses to nature, at times fleeing chaotic reality. It explores family connections too, with the works of fathers and sons shown on the same shelves. “Every piece has a story to tell.”

Unlike in many dynastic changes around the world, new Chinese emperors did not destroy or relegate the collections of their predecessors. “If you possessed the past, you had more legitimacy,” Cao says. “Emperors’ mandates came not only from heaven but also from maintaining the culture of the ancestors.”

The 87 artworks on display in Sydney are “like Chinese art history 101”, Cao says.

“They represent the best of technique and craftsmanship and cultural meaning, and beauty … some of the most beautiful things ever made by Chinese people.”

Heaven and earth in Chinese art: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei is at the Art Gallery of NSW from Saturday to May 5.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout