Exhibition: Alexander McQueen, Mind, Mythos, Muse. National Gallery of Victoria

A new NGV exhibition showcases the late designer’s creations by placing them alongside works by the artists who inspired him.

It’s a tale of two cities, two collections, and two philanthropists. But one monumental designer. From Los Angeles to Melbourne, the exhibition “Alexander McQueen, Mind, Mythos, Muse” attempts to enter and unpick the encyclopaedic brain of the late designer, an unparalleled giant of contemporary fashion over two decades and at the end and start of two centuries.

This month, the exhibition will open at Melbourne’s National Gallery of Victoria after a six-month run at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. It will be the same show in principle and intent, only twice as big and even more dazzling.

-

Discover the world’s best fashion, design, food and travel in the December issue of WISH magazine.

-

The central intent of the show is to highlight not only the beauty and technical wizardry inherent in McQueen’s work, but to put it in the context of his influences and inspirations.

“We really wanted to do something that added to the greater knowledge of McQueen,” Clarissa M. Esguerra, LACMA associate curator, costume & textiles, tells WISH. “There are so many books, so many publications, documentaries, exhibitions – what can we do that’s adding something new to this?

“McQueen was such a student of art and art history and the world. He clearly has encyclopaedic sources of inspiration that span time, place, artists, mediums. And we have that in our permanent collections. What better way to show him than contextualised in art history?”

Working purely with pieces from its own fashion collection, Esguerra and co-curator Michaela Hansen, curatorial assistant, costume & textiles, collaborated with other departments within the museum to bring to life the rich inner workings of McQueen’s design process. And while the pairings are not necessarily the exact artefacts McQueen referenced, they form an acknowledgment of what the curators call “the interdisciplinary impulse that defined his career”.

That process has been mirrored in Melbourne, says Katie Somerville, NGV senior curator of fashion & textiles.

“For us it has been the most wonderful sense of destiny, that this other institution that we’ve always wanted to work with on the other side of the world just happened to have this incredible strength in McQueen and we do, too,” Somerville told WISH.

Similarly, Somerville and her colleagues called upon other departments within the NGV – including painting and drawing, Asian art and photography – to enhance the world within McQueen’s mind.

Visiting the first iteration of the exhibition at LACMA earlier this year brought the concept to life. The first piece of McQueen’s work you encountered was from his final, incomplete, collection of Autumn/Winter 2010/11, which came to be known as Angels and Demons. Designer Sarah Burton completed the collection following McQueen’s death by his own hand in February 2010. The gold-and-ivory jacket is made of jacquard woven with winged angels. Flanking the jacket are three marble sculpture fragments from c. 1460, each of winged cherubs. A dress from the the collection features imagery from Hieronymous Bosch digitally composited in the jacquard; similar colours and imagery are visible in the painting alongside it, by fellow Dutchman Jan Mandijn from the School of Bosch.

Elsewhere, 17th-century Tibetan Buddhist temple hangings and a Chinese trunk are patterned with geometric polychromatic designs that are reworked into a two-tone dress from McQueen; a belt from the Neptune collection of Spring/Summer 2006 features two confronting hippocamps, the mythical beast that is half horse, half fish, beside which are seen a 3rd-century earthenware Italian version, and another from the 16th century featuring a gilt seahorse and a turbo shell.

It’s like seeing a world open up around you.

“McQueen’s work, when you situate it within art history, is a case study of artistic process,” says Esguerra. “We’re just visually expanding what is told in a single garment.”

Both LAMCA and the NGV have enviable collections of McQueen, the largest in a public institution in North America and Australia, respectively. This is thanks to the donations of two fashion-focused philanthropists, American collector Regina J. Drucker, and Melbourne’s Krystyna Campbell-Pretty.

“They’re like our sister institution,” Somerville says of LACMA, “mirroring incredible McQueen holdings as do we, this amazing art collection, as do we. And we have these two extraordinary women who through their philanthropy have had a transformative impact on our collections.”

The NGV has almost 50 McQueen pieces; added to those from LACMA, that will bring the exhibition total to around 110, seen alongside some 70 artworks and artefacts from both institutions.

Where the LACMA presentation was clean, minimal even, with a colonnade-style set in white, the NGV will offer a more immersive experience, incorporating LED screens, soundscapes and additional documentary photography.

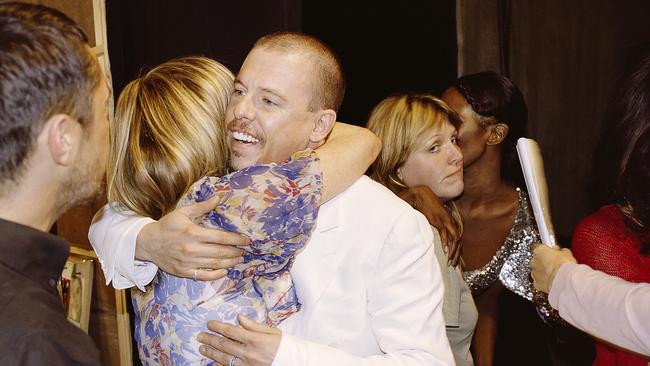

“We’re working closely with photographer Robert Fairer, who documented all but a handful of McQueen’s collections, particularly from the perspective of backstage in preparation for the models going out [on the catwalk], and sometimes as they came back. We’re able to incorporate these amazing photos in the publication and in the exhibition as well where we have this work in our collection.”

There are four sections of the exhibition. Mythos looks at the influence of religions and mythology, including those hippocamps and Bosch-inspired works. It’s followed by Fashioned Narratives, which homes in on McQueen’s unique approach to building his own worlds and stories. Within this section are nods to his personal history, including pieces from In Memory of Elizabeth How, Salem, 1692 (Autumn/Winter 2007/8). Named for an ancestor who was executed in the Salem Witch Trials, the collection includes a velvet column dress embellished with silver bugle beading cascading like locks of hair, a nod to the hair being shorn from women accused of witchcraft so that no signs of Satan could be hidden beneath. This visual motif is mirrored in a 1922 artwork by Ernst Barlach, Lilith, Adam’s First Wife, in which her hair falls in a similar fashion.

In the Widows of Culloden collection (Autumn/Winter 2006/7), McQueen draws on his Scottish heritage, including his clan tartan, and remembers the British violence enacted upon the Scottish in the Battle of Culloden of 1746. Esguerra calls this “one of his most important collections”.

“Both [McQueen] and his mother were fascinated by family history, and [this collection shows] his very strong desire to make sure people are aware that while there’s a lot of romanticising that goes on, there’s a brutal history between the British and the Scots.”

The depth of design detail McQueen undertook in every piece is staggering. A coin-trimmed top and trouser ensemble, from the Eye collection of Spring 2000, apparently had the LACMA team perplexed. “He wanted to talk about ways in which designers in the late ’90s and early 2000s were often borrowing from cultures outside of their own, and he was thinking about the Arab community in London,” says Esguerra. They showed the coins to the experts in Middle Eastern art at LACMA to try to work out their origin or meaning, “only to find it’s a faux Arabic script of McQueen’s name”, Esguerra confirms with a laugh.

While she concedes that death is a constant theme in McQueen’s work, often associated with his skull-print pieces, “we found a lot of hope and humour and playfulness in his work as well”.

Somerville calls McQueen a “consummate storyteller”, adding that sometimes these are completely fictionalised stories that inform his collections. “As was the case with The Girl Who Lived in the Tree (Autumn/Winter 2008/09) – a mix between princess fairytales, colonial India and incredible textiles.”

Victorian dresses printed with anchors and crowns and with military embellishments nod to the imperialism of the time, and stand alongside a 1950s-style dress by McQueen, marking the period following India’s independence.

“It’s a difficult collection to discuss,” says Esguerra, “because there are so many ranging influences in this story he created about a girl who lived in a tree, this feral creature as he called her, living in the darkness of the branches, and it wasn’t until she had the courage to come down that she came to the light. It was inspired by a 600-year-old elm tree [in McQueen’s East Sussex garden].” One strapless black dress was also inspired by A Midsummer Night’s Dream, said to be a favourite play of McQueen, and in the woven jacquard skirt you can make out the donkey-headed Bottom, a direct reference to Arthur Rackman’s illustration of the same.

The mannequin’s headpiece is a cross between antlers and branches, created by LA designer Michael Schmidt, who created a number of headpieces for the LACMA show, and another 50 for its Melbourne sojourn.

Esguerra recounts the installation period of the exhibition, while social distancing was still in play in LA. Schmidt was installing the headpiece, made of wire coated with bark, and decided something was missing. “He climbs up on the ladder and puts this one green leaf for hope, saying, ‘We have to give it life.’”

In the Evolution and Existence section, “we step back and look at the way he drew his inspiration from big existential cycles of life’s trials and the tribulations of humanity, issues around death, desperation, and this idea of the ecological implications of what we’re doing environmentally to the planet,” says Somerville. “I think that’s why he’s so pertinent and relevant and speaks to people so directly to this day, that these issues are bigger than all of us and still so relevant.”

There are examples of McQueen’s work from the collection Dance of the Twisted Bull (Spring/Summer 2002), which was inspired by bullfighting, flamenco dancing and Spain, “and thinking about soft flesh and performance and death”, says Esguerra. The designer was specifically inspired by Spanish painter Francisco Goya y Lucientes, whose painting of a bullfight sits alongside a black strapless dress by McQueen topped by a bullhorn hat from Schmidt, but also a suite of ink images by Picasso, themselves inspired by Goya.

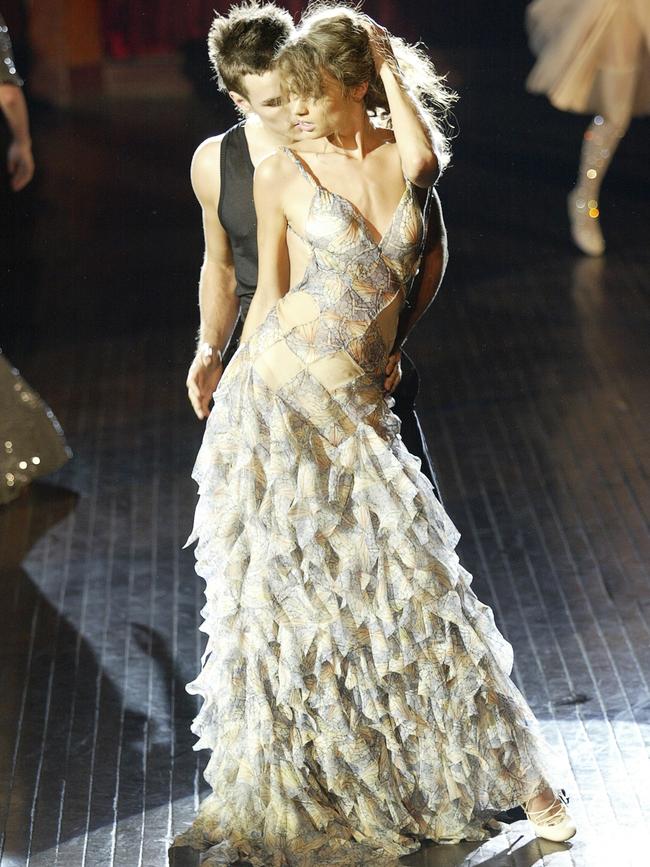

The Deliverance collection of Spring/Summer 2004, presented on the catwalk as a choreographed dance piece by Michael Clarke, was in part inspired by the 1969 film They Shoot Horses Don’t They?, about a Depression-era dance marathon that becomes for some a dance to the death. Scenes from the film play alongside custom mannequins in dance poses wearing 1930s-inspired silk dresses and shorter panelled flip dresses in jersey.

Of course, the Plato’s Atlantis collection, McQueen’s final fully realised catwalk collection from Spring/Summer 2010, looms large in this section. The engineered digital print dresses – which pushed the boundaries of this new technology at the time – often replicate reptilian skins, while leather details appear to form part-carapaces.

“The whole premise of the show was him reflecting on the state of the planet,” says Somerville, “and that perhaps if we continue in this way we might really be faced with having to do reverse evolution, returning ourselves to reptilian sea creatures in order to survive.”

Alongside the dresses “we’ve got some extraordinary historical and contemporary ceramics that have this wonderful reptilian and sea creature imagery, but also photography that relates to Antarctica and the Arctic and how they play a role in terms of our captured imagination around [rising] sea levels.”

Technique and Innovation moves away from conceptual storytelling to focus on McQueen’s mastery in tailoring and construction from his time on Savile Row and working in costume design. Pieces are organised by method, including surface decoration and deconstruction, and are partnered with historical garments from as far back as the Victorian era as reference points. McQueen’s styles range from perfectly feminine 1920s-inspired sequinned cabaret dresses through to sharply tailored skirt suits with perfectly aligned mini checks, which Esguerra describes as a “master feat of tailoring”.

Like Esguerra, Somerville hopes the show will ultimately present McQueen in a new light.

“There are two things we hope people really come away with,” she says. “This sense of how extraordinary he was conceptually in terms of synthesising all these incredibly disparate sources, whether it was music, contemporary sculpture, cinema or Christian relics, to come together into these incredible pieces, but also the extraordinary technical capacity he had.”

-

In the studio with LA designer Michael Schmidt

The walls of Michael Schmidt’s studio in the Arts District of Los Angeles are covered with magazine pages and photographs of celebrities captured in his captivating ensembles. Tina Turner belting out a tune in a broad chainmail dress. Lady Gaga on the cover of Rolling Stone seemingly wearing nothing but bubbles. Lil Nas X in the gold carapace that was just one layer of his Met Gala look in 2021.

“That was a fun one,” Schmidt tells WISH. “Armour, but make it tear-away.”

While the main gig for the designer and his team is showstopping looks for the entertainment industry, he was also asked to create the headpieces for “Alexander McQueen: Mind, Mythos, Muse” – a final flourish to augment the clothes and silhouettes on show. The initial brief was just for LACMA, but when WISH visits him in late August he is in the throes of finishing an additional 50 pieces for the NGV’s iteration.

Schmidt brings to the exhibition not only his prodigious talent for “adapting unusual materials to the body”, but a more personal element.

“[McQueen] was an acquaintance of mine, and I was always astonished by his humour and reflectiveness and wit, of course,” he says. “He was in London, I was in New York, but when he was in town I would see him. He’s never out of mind. This is not a masturbatory exercise; I’m doing this hoping that he would love it.”

While McQueen would undoubtedly have been chuffed with the way the headpieces continue to tell his multilayered stories, Schmidt takes a broader view of the project.

“Each collection was unique unto itself and was telling a story and I’m trying to keep within that feeling, respecting his wishes. But then his vocabulary was so large, of materials and styles, I’m feeling a bit of freedom to take an idea from one collection and put it in another, because then you end up with an overall narrative of his story.

“When you consider his entire career, it’s a language, and that language is interchangeable and only reflects back on McQueen. He’s one of those few designers whose ideas are so forward thinking and so unusual and so previously unseen that they’re distinctly his.”

The pieces Schmidt made for the LACMA show used a typically wide and unusual range of materials, such as wire wrapped in bark for the antler-branch piece, and gold leaf bunched together as a kind of fur hat. Pieces for the Plato’s Atlantis section used candy wrappers and plastic six-pack rings.

“That is one of my favourite collections, which is a hard thing to say. Being the story of evolution and us ultimately reverting back to the sea, I said, what would a woman who has gone through this process embellish herself with? Things she finds in her environment, which would unfortunately be trash. But you’ve still got to make it beautiful.”

Around the studio are the pieces being prepped for Melbourne. They include crystal flower garlands, a branched coral style covered in Swarovski crystals, and another with strips of gold-leaf hessian wrapped around the head with crystal extrusions forming a mohawk. A chainmail head covering has short spikes that Schmidt runs his hands through: “McQueen loved chainmail as much as I do, so this was one that I just wanted to play around with, the abstract concept of fur, but an anemone kind of vibe.”

Over on the wall are small concept drawings. Pointing out one of them, Schmidt says, “These moths are robotic and they actually flutter. I’m very, very excited about that one. And this one is a mobile where the birds actually circle about the head.”

He’s experimenting with pine cones and porcupine quills, moss, and even a resin model of a sabretooth tiger skull.

“While these are showy pieces that we’re doing because his clothing demands that, you have to have pieces that will hold up to it and help tell the story. As much as I adored him and worship his brilliance, I have to approach it from my own viewpoint. That’s what makes it not only about what inspired him, but the others he inspired, of which there are legion. I am simply one of the lucky ones who get to contribute to telling the story.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout