Alexander McQueen: designer’s rise and fall

Colin McDowell, who met Alexander McQueen in 1996, remembers the man behind the headlines

‘Fashion commentators are so poncy,” 27-year-old Alexander McQueen told me the first time I interviewed him in March 1996 for The Sunday Times. “They keep saying London’s changing, getting better. That’s a diabolical lie. Look at my studio. Three days after a show and there’s nobody. Not a buyer. There’s nothing in London. If I didn’t have Paris and Milan for selling, where would I be? Great show? Who cares?”

The newspaper had sent me to meet the fledgling fashion star, known to his friends as Lee, in his tiny studio in Hoxton, east London. It was an incongruous space that smelled slightly of damp, yet was filled with the most beautiful clothes. It was four years since his graduation show, and I remember him calling me “sir” (as a teenager he had, apparently, asked his mother, Joyce, for a copy of my book on 20th-century fashion for his birthday, and it was one of his favourite reads).

I interviewed him again seven years later, in 2003. By this time he was an established and powerful figure in international fashion, having been made creative director at Givenchy in October 1996, and later, in 2000, receiving the financial backing of Gucci for his own brand. Amusingly, if my name came up, I was told he now greeted it with a stream of obscene invective, much of it including the f- and c-words. (He even went so far as to ban me from one Givenchy show after an unfavourable review.)

Next week a documentary film called McQueen, devoted to the rise and fall of the designer in both his personal and creative life, premieres in Australia at the Sydney Film Festival. The producers spent a year trawling through 200 archival sources to splice together 111 minutes of never-before-seen home movies, rare interviews and audiotapes made over the course of McQueen’s life. Combined with new commentary from colleagues, partners, friends and, most revealingly, family, the story the documentary chronicles gives a uniquely clear portrait of him.

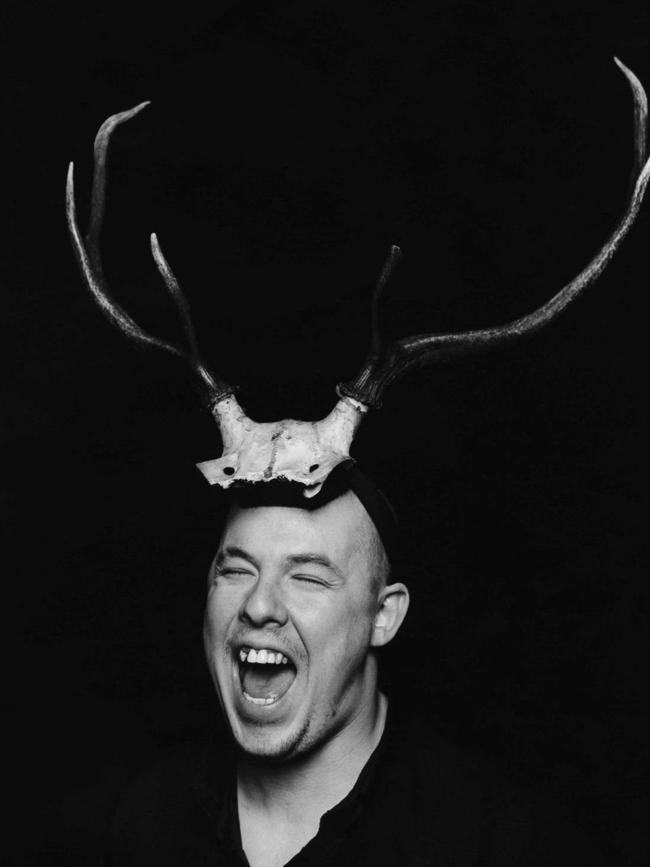

In person, McQueen was shy and tongue-tied, and didn’t like to be filmed or photographed much; the personal footage that makes up the bulk of the film is certainly the exception, not the rule. In fact, during his first few seasons he refused to show his face to the camera during interviews, because he was still on the dole and technically supposed to be unemployed.

He was the youngest of six children and grew up in a tough, working-class east London area. His father was a cabbie, born of a generation where men were meant to be men, and McQueen once described himself to me as the “pink sheep” of his family. In the early shots of him as a schoolboy, we see his absolutely unwavering determination to be a designer. His mother encouraged him in everything he dreamed of, and clearly he adored her. One of the most tragic details of his suicide on February 11, 2010, is that he killed himself on the day before his mother was to be buried.

It was Joyce who suggested he should try to get an apprenticeship with a tailor, which led to his formative time at Savile Row tailors such as Anderson & Sheppard and Gieves & Hawkes.

In the documentary, McQueen’s oldest sister, Janet, and his nephew Gary talk honestly about him and his upbringing, and it is plain his family gave him support, not least when he came out as gay at 18.

But he also witnessed family trouble, including violent attacks on Janet by her first husband — the same man who had sexually abused McQueen as a child and teenager.

When he came to study at Central Saint Martins, it was his aunt Renee who funded his degree. The influential stylist Isabella Blow (who was fashion director of Britain’s Style from 1997 to 2001) famously bought his entire 1992 graduate collection, paying him in instalments of £100 a week. As McQueen says to camera: “When I met Isabella Blow, I said, ‘I just want money.’ I was desperate for money.”

But Issy gave him much more than just that, singing his praises everywhere and wearing his clothes, no matter how outlandish. She was a true eccentric. I saw her often at the shows, and she invited me once or twice to Hilles, her home in the Cotswolds, a zoological kind of place filled with all sorts of aristocracy.

In the morning, she often cooked bacon and eggs for her husband, Detmar, dressed in a Schiaparelli fur coat. McQueen was a regular at Hilles, and he began to learn about educated taste and behaviour from Issy, a bit like Eliza Doolittle and Professor Higgins. The two were inseparable. As McQueen said: “Isabella is my Tweedledee to my Tweedledum.” She introduced him to fashion’s power players and helped to broker his crucial deal with Gucci.

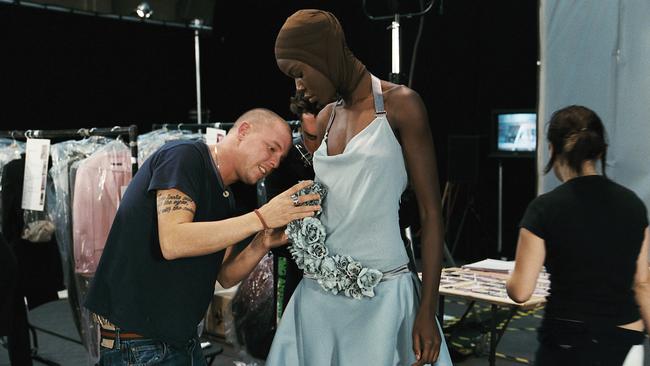

During my years as fashion writer, I frequently found myself at odds with my fellow hacks in that I did not always rate McQueen’s fashion, although I always found the drama of his shows moving. He created some of the most ravishing clothes of the 20th century and set them in situations that overshadowed them: the model Shalom Harlow being sprayed by a robot with black and yellow paint for his No 13 collection in 1999, or the hologram of Kate Moss in Widows of Culloden in 2006, which was recreated for the wildly successful Savage Beauty exhibition devoted to his works.

Paradoxically, one of the most memorable moments came in 1997 when some old cars used to dress the set of It’s a Jungle Out There caught fire due to the antics of student fans gatecrashing the event. None of us had any idea what was going on — McQueen being McQueen, he kept sending models down the catwalk.

Though there was drama, there was not much joy in his shows. As McQueen himself says in the documentary: “It’s like exorcising my ghosts. The shows are about what’s buried in my psyche … I would go to the end of my dark side and pull these horrors out of my soul and put them on the catwalk.”

In later years the pressure of producing so many collections (McQueen ready-to-wear, pre-fall, resort, menswear, the McQ diffusion line and accessories) weighed upon him and he came to rely more heavily on drugs and alcohol. He became increasingly paranoid and self-doubting, and then, as Gary says in the film, after being diagnosed with HIV he began to suffer more seriously from the depression that had always been latent but controllable.

“I think there is more to life than fashion, and I don’t want to be stuck in that,” he says. “I am Alexander McQueen and I can’t leave that at the door at the end of the day. I have to go home with myself.” And that he found increasingly difficult.

Some of his most famous friends and collaborators are notably absent from the documentary: milliner Philip Treacy; socialite Annabelle Neilson; and Sarah Burton, who started as an intern at McQueen and took over as creative director after his death. Despite its length (I would have left at least 20 minutes on the cutting-room floor), the McQueen film is a worthwhile endeavour that leaves a useful record of a Dickensian life — half Great Expectations, half Oliver Twist, quintessentially London, but with a worldwide resonance.

THE SUNDAY TIMES

McQueen screens as part of the Sydney Film Festival on Friday.