Betty Churcher’s blockbuster life: woman taught nation to see

Australia’s art whisperer, Betty Churcher, got her final wish.

Australia’s art whisperer, Betty Churcher, got her final wish.

“I don’t want to live beyond 85,” she told me squarely with a spirited cackle as we shared lunch last March in her sunlit loungeroom full of paintings that spoke of her singular passion “for the unadulterated magic of art”.

Her statuesque body already failing, she was determined not to become a burden on her four sons, who were gathered around her when she slipped away on Monday night, aged 84, from cancer.

As clever with words as she was with the stub of her pencil, Churcher conjured an image of her own elderly mother impatient for her daughter’s arrival “with vacuum cleaner and polisher” to clean the house. “And I thought I’d never do this to my own children,” she said with a laugh.

With a sliver of sight in eyes dulled by macular degeneration and her piercing, intelligent mind, she confessed to things I couldn’t publish, illuminated details I’d never noticed in iconic Australian images, and stepped me through an extraordinary career that began in Brisbane with a child’s sketchbook and swept her to the country’s cultural pinnacle as director of the National Gallery of Australia.

Her artist husband, Roy Churcher, who died in December, was then in the early stages of dementia and she fretted at what would happen when she could no longer drive them both around. He stayed in the background, physically strong, content to fetch and carry at her prodding.

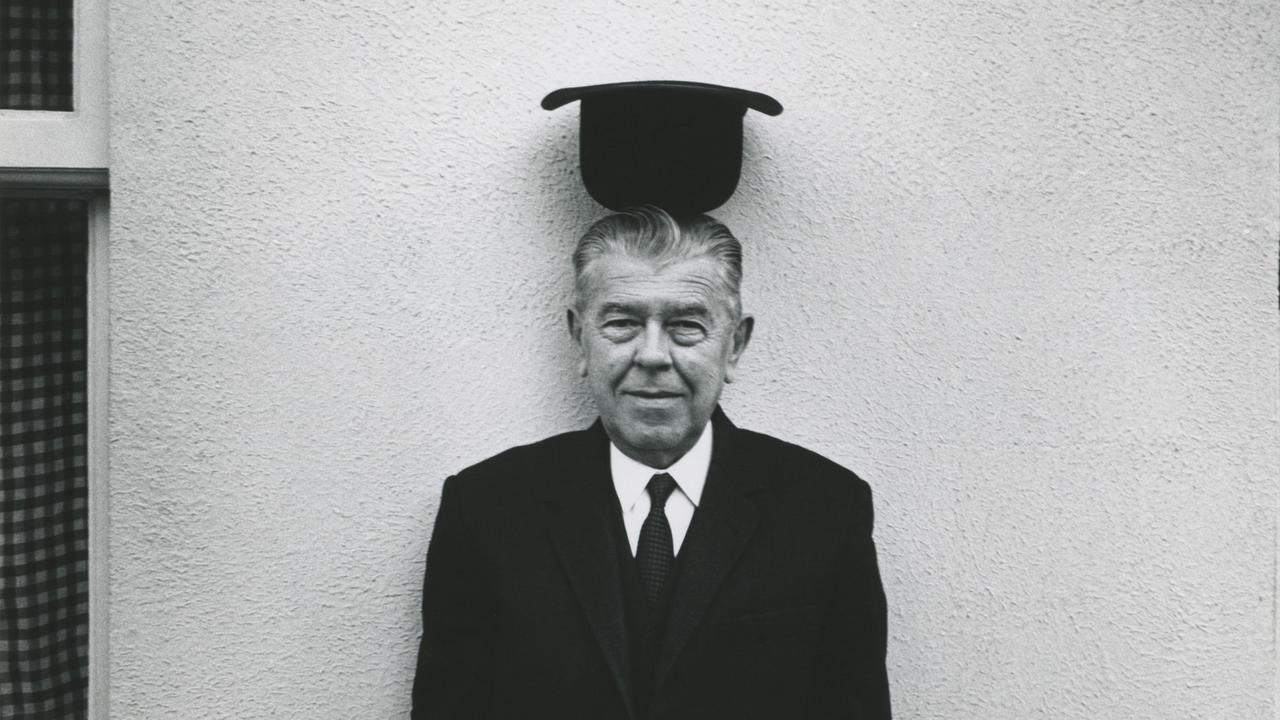

Her sculptural face with its helmet of grey hair seemed ageless, even though she likened herself to an old Ferguson tractor: “Don’t look under the hood.”

Self-deprecating, droll and wise, she was a great seductress even confined to the dining room chair where she sat, since she could no longer walk any distance, relying on her unbridled enthusiasm for bringing art within reach of us all.

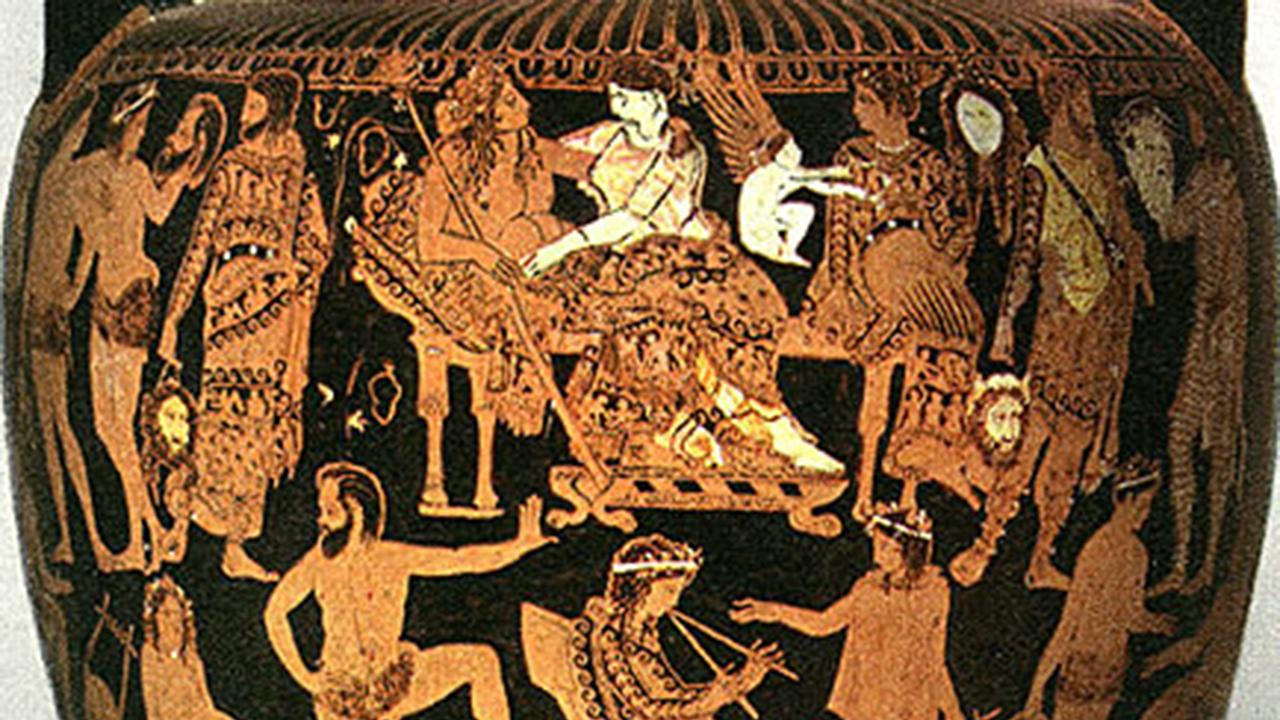

She won over prime ministers. “Keating was terrific. A connoisseur. He was always trying to encourage me to buy late classical works which weren’t relevant to the gallery, but he knew how much everything went for at auction because he read all the catalogues.”

International peers adored her. The director of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor, told me that when the words “Mrs Churcher is on the telephone were spoken … the effect was like an electric charge. ‘Betty! How wonderful!’ was the first thought … But then came the second thought: ‘What does she want?’… and it always ended one way: ‘Betty, you can have what you want’. (She) is and always was irrefusable.”

But mostly she mesmerised the public. They flocked to the galleries she ran in Perth and Canberra; they watched her ABC television programs, Take Five and Hidden Treasures, then towards the end they read her Notebooks, each illustrating cherished works with sketches done often from a wheelchair.

We did a drawing of each other as we sat at the table in the fading afternoon light. “I don’t look old,” she spotted the flaw in mine immediately. “If you use mine you’ve got to use yours,” she insisted. Later, as she leafed through Australian Notebooks, she picked apart her own sketches: “See what I did wrong”.

Her commentary carried nuggets of enlightenment, which was a gift that distinguished her in the classroom where she taught briefly before engaging the wider community as an interpreter of art. When her son, the artist Peter Churcher, came to her for criticism she strived for honesty. “I can’t see the point in him sending his work if I don’t.”

She steered the talents of granddaughter Charlotte with similar frankness, encouraging them both to let their pictures or prose speak louder than the artistry behind every work.

She felt her husband Roy “should have agonised more”.

“Teaching underpinned me,” she said of the blockbuster exhibitions she lured to Canberra hoping desperately that others might fall in love with a Vermeer, a Rembrandt or a Titian just as she had been awestruck in her childhood by Blandford Fletcher’s painting Evicted at the Brisbane gallery.

Australian artist William Robinson, who taught drawing to apprentice hairdressers alongside Churcher in the late 1950s, emailed her before her death. “You had a profound influence on me … I heard what you said to your students … and I took in every word you said to me about art and life.”

Her career happened almost by accident.

She gave up painting to raise her family because she knew she couldn’t devote equal levels of emotional intensity to both.

In a series of emails we exchanged after our day together, she described how she’d initially knocked back the National Gallery job in 1990 when Canberra tried to lure her from the Art Gallery of Western Australia, where she’d been installed by the late billionaire Robert Holmes a Court in 1987. “Then a good 10 days later Robert did something … it was the straw that broke the camel’s back.

“I remember sitting at my desk with my head in my hands …. then I reached for the phone and the rest is history.”

Later, she sent me a coda to this tale. “The pilots were on strike so they wanted to fly me across on a Hercules. I couldn’t face the long journey in one of those great rattlers so I said ‘No’.”

Of course they found her a commercial flight. “This points to the fact that I had no burning ambition for the top job, as it was called,” she wrote.

All she cared about, she told me, was running a gallery as well as she possibly could, engaging her audience, lifting them up, inspiring them with her “abiding passion” for remarkable works of art.

As we sat in her loungeroom overlooking gentle hills that dipped towards a trickle of the Yass River not far from Canberra in southern NSW, she was philosophical about death.

“I’m beginning to dread the nights,” she conceded.

She was not a Buddhist, but accepting life’s cycle infused her desire to do everything she could with the time she had.

“Until you can face the vulnerability and temporary nature of life you’ll never be happy,” she said. “I don’t regret a thing.”