How Last Days of the Space Age brought the ‘70s to life

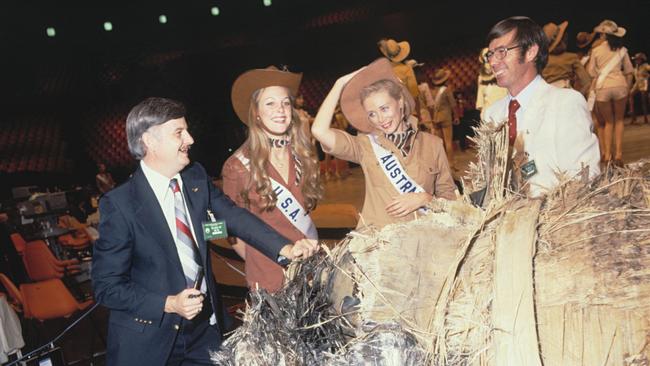

In July 1979, Perth was host to a truly unusual spectacle: the Miss Universe pageant, where poised and glamorous contestants, draped in sequins and silk, vied for attention with an unexpected contender – a hulking slab of space junk.

In July 1979, Perth was host to a truly unusual spectacle: the Miss Universe pageant, where poised and glamorous contestants, draped in sequins and silk, vied for attention with an unexpected contender – a hulking slab of space junk.

This was the year that Skylab, the first US space station, made its fiery descent into Earth’s atmosphere. Launched into orbit in 1973, Skylab was cobbled together with surplus Apollo 13 components, affectionately dubbed “the can” by astronauts. By 1978, the laboratory was beginning to fray at the edges – a surge in solar activity had expanded the Earth’s atmosphere, increasing drag on Skylab and pulling it perilously closer to Earth.

NASA had hoped to extend its life by boosting it into a higher orbit with the soon-to-launch space shuttle, but delays sealed Skylab’s fate, forcing the agency to opt for “death method No. 3 ”: guiding the space station to a controlled descent into the Indian Ocean.

In the weeks leading up to the crash, NASA warned the public about Skylab’s descent. At first there was panic – racing headlines, anxious scientists calculating just how much damage a rogue spacecraft might cause.

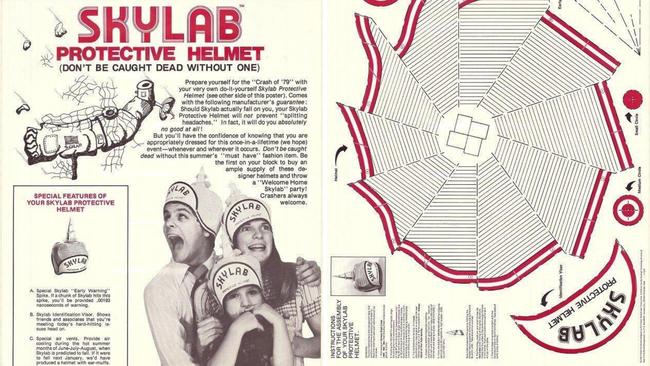

But the fear quickly turned into humour. Bars started serving Skylab cocktails with slogans such as “Drink a couple and you won’t know what hit you”. A North Carolina hotel declared itself an “official Skylab crash zone” and hosted a disco party in celebration. Enterprising opportunists cashed in on the event, selling tat: T-shirts emblazoned with bullseyes, DIY cardboard helmets, and cans of “Skylab repellent”. In Perth, bookmakers opened bets on where Skylab might land. As news spread that Skylab was on a trajectory towards Australia, bookmakers in Perth opened bets on where, precisely, it might touch down.

As it plummeted back to Earth, most of the station disintegrated on re-entry, as expected. What NASA hadn’t counted on was that Skylab would remain intact longer than anticipated – several thousand kilometres farther down its orbital track. Its destination? The West Australian port town of Esperance.

Meanwhile, 800km away, another show was unfolding in Perth – the Miss Universe pageant.

In one of the strangest double bills in history, the charred carcass of one of Skylab’s oxygen tanks was transported to the event, where it shared the stage with the pageant contestants.

This unlikely pairing inspired Last Days of the Space Age, a new eight-part drama series from writer David Chidlow, set to premiere on October 2 on Disney+.

Chidlow was just a wee boy living in North Wales when Skylab crashed, but he tells The Australian over Zoom: “I remember it vividly.”

“They were selling tin hats with targets on them and stuff like that,” he says. “It was crazy because no one knew where this thing was going to crash at all.”

Chidlow emigrated to Melbourne in 1983 when paranoia about the Cold War was at its peak. He remembers building a nuclear fallout shelter with his best friend, Johnno, in the scrub at the end of their cul-de-sac in Frankston. By his own admission, they were “a bit rubbish” at being teenagers.

“We wouldn’t have made a John Hughes film,” he says. Years later, reflecting on his childhood D-Day prepping ventures, Chidlow realised that what he was hiding from wasn’t nuclear war but adulthood itself.

“We were building a cubby, wanting to escape adulthood as it was sort of crashing down,” he says. “This idea of a big thing coming down that you have no control over, representing adulthood crashing in, felt really powerful for me. I connected that to Skylab.”

Two decades ago, Chidlow began writing a script inspired by Skylab, with dreams of making a feature film about a lonely teenage boy who yearns to be an astronaut. That film never materialised but the story wouldn’t leave him.

He continued researching the crash and found himself fascinated by Perth’s cultural landscape at the time, particularly a telecommunications plant strike that paralysed communication in the most isolated city on Earth.

These events coalesced, and Last Days of the Space Age was born. Set against the backdrop of Skylab’s descent, Last Days of the Space Age chronicles the lives of three families in a small coastal community in Perth.

The working-class Bissett family finds itself divided as the husband (played by Chicago Fire’s Jesse Spencer) takes part in the strike, while his wife (Radha Mitchell), in a managerial position at the same company, is a de facto scab.

Meanwhile, a First Nations family, led by matriarch Deborah Mailman, grapples with the weight of their past, and a Vietnamese family that has fled the war struggles to adapt to life in Australia while hiding secret pain.

“The show has a distinct tone – a tension between the absurdity of what’s coming down and the grounded reality of these lives,” says Chidlow, who worked under the tutelage of the great television writer Jimmy McGovern (of Cracker fame). As “a Pom”, he believes humour will always triumph over pathos. “So that it doesn’t become too leaden.”

Chidlow’s fondness for the era also informs the show’s setting. “There’s tension there, and suddenly you have Donny Osmond on stage at Miss Universe and a space station crashing down. I think it gives a sort of punkiness to it.”

Things were changing in the late 1970s. Margaret Thatcher had come to power in Britain, and a second wave of feminism was radically reimagining gender roles – all of which trickle down into the family dynamics in the series.

“It’s a world that, if you squint, looks a little bit like ours,” Chidlow says. “It feels like a good place to go to make a show that allows us to talk about the now and do it just enough removed that we can feel comfortable with that.”

It’s a cliche to say the setting is a character in itself, but watching this series you are struck by how richly suburban Western Australia in the late ’70s has been rendered on screen – and how rare that is.

Nailing the look so it felt authentic, not like chintzy retro slop, took a killer team and a “huge amount” of research, Chidlow says. As a writer, he had already done much of the grunt work, including a one-week sojourn at the State Library in Sydney, poring over old copies of The West Australian under a microfiche reader.

But Chidlow is the first to say he can’t take any credit for how it turned out – that praise is reserved for the power duo of production designer Penny Southgate and costume designer Nina Edwards. He likens his first day on a pre-production set to being in the film Being John Malkovich. “It was like walking into my own brain. Nina and Penny had just laid out the ’70s – it was absolutely extraordinary. And the level of attention to detail grounded it; it felt real and never slipped into a caricature of the ’70s.”

Southgate, perhaps best known for her dreamy, pastel-drenched work on the ABC hit Please Like Me, jumped at the opportunity to work on the show.

“It was a period I grew up with. I had a great sense of nostalgia about it. Most of the research was in here,” she says, with an exaggerated tap to the noggin.

“It was from memory and I think that’s kind of good because it’s not necessarily completely accurate but it gives you a feel, gives you a vibe.”

When memory grew hazy, there were always vintage copies of The Australian Women’s Weekly to fall back on.

Southgate’s nostalgia for the era manifested most vividly in “the classic WASPy Anglo” Bissett house, one of the central sets of the series, which was based on her own childhood home. That house is all angled timber panelling, arches that reminded Southgate of Play School, gaudy wallpaper and a palette of creamy golds and muted greens that sit on the right side of vulgar. “I wanted it to be very warm,” she says. For Southgate, the colours were the trickiest part, and she worked closely with Edwards to ensure the palettes didn’t clash and the costumes didn’t disappear.

For Edwards and her costume department, the greatest challenge was striking the balance between sexy and suburban. When you think of the late ’70s, images of the sultry, shimmering debauchery of Studio 54 typically come to mind. But this was Perth, worlds away from Bianca Jagger riding in on a white pony. “They were very suburban,” Edwards says. “Back then, it was very basic – lots of knits, jeans, pants and T-shirts.

“You have to go into each character. You read the script and do this massive breakdown of each person’s journey. I like to go into the whole background. What do they do on the weekend? What do they like to eat?”

The costume department sourced a good chunk of original pieces from the ‘70s – some treasures from House of Merivale, the first speciality fashion boutique in Australia, crop up in the show – but the team couldn’t rely solely on vintage finds.

The biggest hurdle was sizing: “There was no vintage I could find that was over a size 12,” Edwards says. So? “We made a hell of a lot of things. We had a workroom set up permanently.”

From there it was an endless cycle of sourcing vintage and new fabrics to make everything from school uniforms, slinky jumpsuits, power plant overalls and a costume for a kangaroo mascot.

One dress, a Gucci-inspired emerald green jumpsuit worn by a Miss Universe contestant from the Soviet Union, needed five copies because of a scene where she gets drenched in red paint.

Dressing the beauty queens in a manner that reflected their culture was a mammoth undertaking. “I just started buying and buying and buying and buying glitzy things from overseas – prom dresses, wedding dresses,” Edwards says. “I started thinking: ‘God, we’re not going to get this’, because there were just so many costumes.”

Edwards, like Southgate, also mined her past for inspiration, starting with her childhood Barbie dolls. “Before I made my own clothes, I made clothes for my Barbie,” she says. The tiny, hand-stitched velvet bomber jackets and other wacky outfits are still with her, “a time capsule from the ’70s”, she says.

While her specialty is costuming for period dramas, with recent credits including the World War II-set drama While the Men are Away, she confides that costuming the ’70s is her favourite work assignment. “I was a young kid in the ’70s. I know it. I wore it. I lived it,” she says.

“It just puts a smile on everyone’s faces. Whenever I’ve done a ’70s job and you’ve got to do the fittings, the actors just get so into it. Especially the men.” Why is that? “Probably because they just wear the same jeans, pants and T-shirt every day of their life. In the ’70s they get to put on some heeled shoes or boots, and some crazy jackets, and they love it.”

She says lead actor Spencer was “lucky because he didn’t have to wear short shorts”, while the rest of the men did. Did he look ridiculous? “No. It’s more that the director was worried he was going to be the hot guy from Chicago Fire in short shorts.”

Spencer, however, didn’t feel lucky at all. He felt left out. “I was really into wearing them!” he says. “They’re like the old footy shorts they used to wear and I wanted to wear the footy socks of the local Perth team … I got denied on that.”

Returning to Australia after years of working in the US was more than a professional move for Spencer; it was a deeply personal one. “It brought the Aussie out in me,” he says. “It was the colour and the clothes and every little detail on set down to the taps.

“I was looking at those taps with the symbol on top, and it was just flashbacks of memory.”

The nostalgic comforts of these everyday details, though striking, are not the core of Last Days of the Space Age. What makes this show resonate, Spencer says, are the universal threads that bind the story together: “Families fighting each other and fighting for each other.”

He expresses confidence that the show has the potential to attract a global audience, though he adds with a laugh: “They might have to put subtitles on some of the colloquialisms.”

Last Days of the Space Age will stream on Disney + from October 2.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout