Skylab panel a fragment of America’s lost space dream

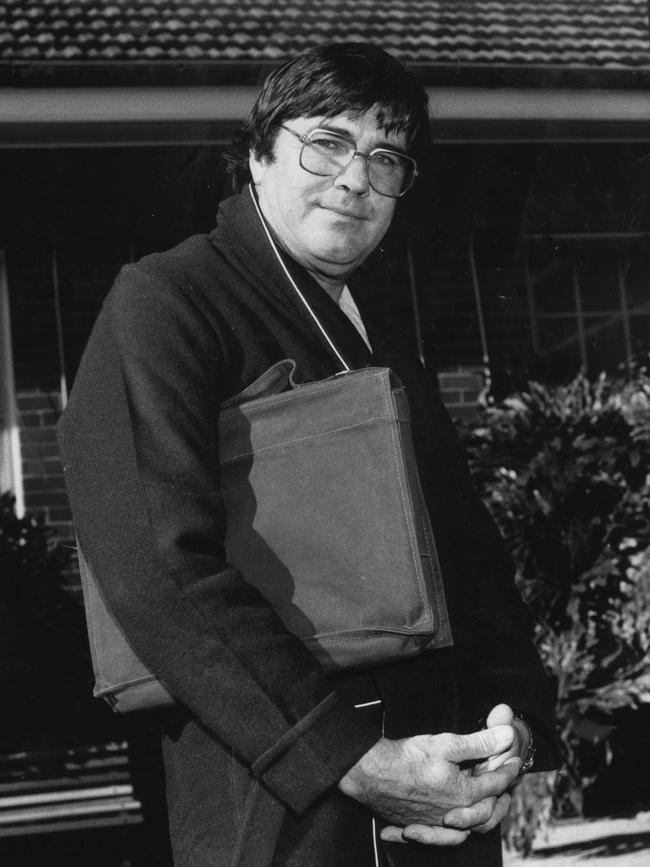

After the space station fell to earth in WA in 1979, a panel ended up in the hands of engineer Ben Lexcen.

An unearthly flash in the night sky traditionally heralds an unidentified flying object. The flying object that lit the heavens over Esperance in the early hours of July 12, 1979, was both identified and expected, although it was a little late, and most of the skywatchers had turned in.

No man-made object had fallen from orbit so large as the 25m, 70-tonne Skylab. The chance of debris hitting anyone was computed at one in 152, which persuaded the National Aeronautics and Space Administration to try steering it away from populated areas by adjusting its orbital inclination.

In fact, Skylab was slower to incinerate than anticipated, and re-entered the earth’s troposphere with a half-dozen echoing sonic booms, showering debris over a wide area.

The largest artefact, a fuel tank that now takes pride of place in the Esperance Museum, was not discovered in bushland for 14 years.

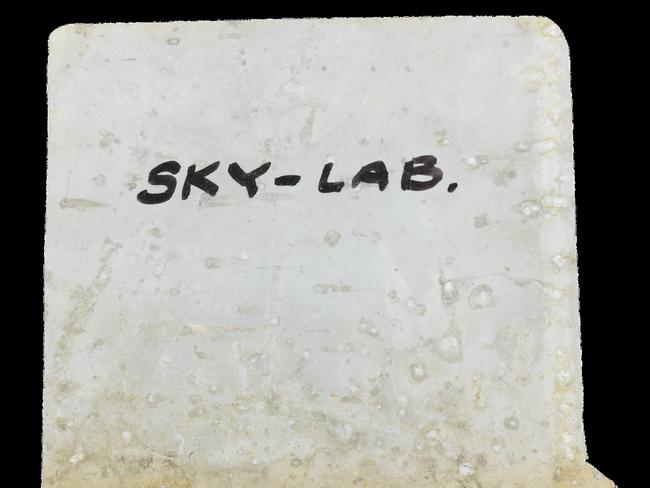

This fragment of honeycombed insulation panel is smaller, about the size of an A4 sheet, but unusual in its lack of charring, and notable for its provenance. It is now in the West Australian Museum in Perth, and was part of a collection of memorabilia accumulated by the late Ben Lexcen, maritime engineer extraordinaire.

At the time of Skylab’s fiery fall, Lexcen’s name was barely known outside sailing circles.

He was at work designing Australia, unsuccessful contestant in the 1980 America’s Cup, preparatory to designing Australia II, legendary winner of 1983. Perhaps it had a symbolic quotient as American ingenuity humbled – which was, of course, Lexcen’s long-term objective.

Skylab, still the only American space station, was assuredly ingenious – a project designed, partly, to use leftover bits of the Apollo program, which had ended in December 1972.

Skylab was a repurposed S-IVB – the third stage of a Saturn V booster – with a docking adapter, a telescope and solar panels.

The interior was fitted out as an “orbital workshop” with facilities for human habitation and experiment.

Skylab was occupied for 24 weeks between May 1973 and February 1974. But delays in the Space Shuttle program then precluded plans to boost it to a higher orbit, leading to interesting questions about the status of its remains.

In Creedence Clearwater Revival’s great song It Came Out of the Sky (1969), the farmer Jody, surrounded by paranoia and exploitation, expects to get paid for what’s landed on his property: “Jody said it’s mine / But you can have it for seventeen million.”

In fact, under the Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies of October 1967, any debris from an American spacecraft automatically becomes property of the US government in the event of landing on that country’s soil, and can be “requested” if it falls anywhere else.

The US explicitly waived that right for Skylab, largely out of mortification.

The January 1978 re-entry of a Soviet satellite with nuclear elements had similarly embarrassed Moscow.

“I was concerned to learn that fragments of Skylab may have landed in Australia,” said president Jimmy Carter at the time. “I am relieved to hear your government’s preliminary assessment that no injuries have resulted.”

A $400 littering fine jokingly levied by the West Australian government went overlooked – it was later paid by a good-humoured Californian disc jockey.

Having snaffled his souvenir of the flash in the sky, Ben Lexcen returned to designing a flash in the sea.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout