Jacob Elordi shines through fog of war in the Narrow Road to the Deep North

Australian star Jacob Elordi didn’t hesitate when Snowtown director Justin Kurzel came calling – even if it meant monastic living in pursuit of cinematic truth.

When Jacob Elordi was a teenager and an aspiring actor, he saw Justin Kurzel’s Snowtown and afterwards wrote the filmmaker’s name down on a piece of paper. A small act of manifestation from a boy in Brisbane with big dreams and a jawline destined for global superstardom.

A decade later, now one of the most in-demand actors on the planet – Bottega Veneta campaigns, Euphoria fame, a turn as Elvis, and the star of one of Netflix’s biggest-ever films, The Kissing Booth (just don’t ask him about that …) – he finally got the letter he’d been hoping for. It was Kurzel, asking if he’d want to star in his new project. Elordi didn’t hesitate.

“He could’ve handed me whatever,” he grins. “I’m such an enormous fan that it wouldn’t matter.”

“Whatever” turned out to be the sprawling five-part series, The Narrow Road to the Deep North, an adaptation of Richard Flanagan’s Booker-winning novel and Kurzel’s first foray into television.

I meet the director and his leading man in a hotel room at the Park Hyatt in Sydney. Kurzel is dressed in a T-shirt from not-for-profit organisation NOFF, which reads, “Eating Salmon? Killing Tasmania”. Elordi, meanwhile – all six foot five of him – is zipped into a silky Willy Chavarria tracksuit, with a gold cross zip dangling at his chest like a communion medal.

The Narrow Road to the Deep North is a harrowing and lyrical novel about the 13,000 Australian prisoners of war who, in 1943, were forced to work on what became known as the Death Railway – a 415-kilometre track carved through the jungles of Burma and Thailand under the command of the Imperial Japanese Army. They were denied medical attention, starved and brutalised by guards. Nearly 100,000 Allied POWs (including some 3000 Australians) and Asian slave labourers perished during its construction.

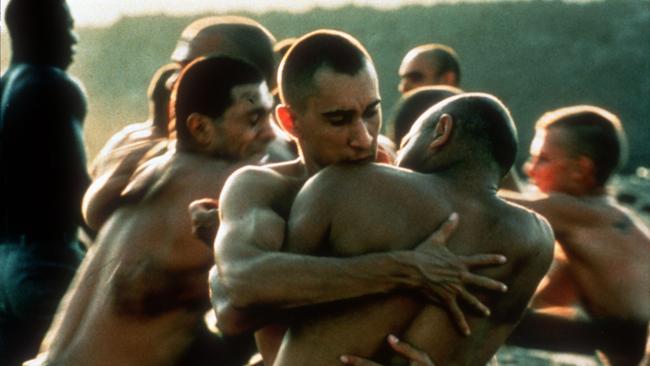

Kurzel, a longtime friend of the author, says he never wanted to make a literal war film. “I thought what was really beautiful and interesting about the book was that it’s all told through memory,” he says. He was interested in the bond the men shared – how it helped them survive the horror. “I wanted to keep the lens on how these boys survived it through their connection, intimacy, and sort of love with each other. That was at the forefront.”

The director knows a thing or two about the male psyche in extremis. He made his name with films about violent men in crisis – Snowtown, The True History of the Kelly Gang, Nitram. And while the show is unflinching and, at times, unbearably gruesome, there’s a tenderness here that feels new for him.

The Narrow Road does not look like the war films we’re used to. The way the soldiers are filmed is almost sensual – the closest comparison would be Claire Denis’s 1999 wartime romance, Beau Travail (“One of my favourite films,” says Kurzel).

“Richard describes the jungle as this ghoulish, gothic place where they lit fires around the edge of the POW camp and tigers would come out in the night. It conjured up something very different from what I’d seen before with these types of films.”

Kurzel admits that, at times, he was overwhelmed by the story and the scale of what the men were building. But conversations with Flanagan assured him the story was in the minutiae. “It’s about what they (the soldiers) saw, it’s about the way the man’s hand is resting on another man’s shoulder. It’s about the one grain of rice. It was all about bringing the camera in much closer,” Kurzel says.

“That started something for me. It released me from having to worry about hitting a certain visual ambition for it, or a literalness. We’ve got all these big war moments. It was really about: How do you go into this very human experience?”

The Narrow Road unfolds across three timelines, following Dorrigo Evans, a soldier-surgeon portrayed in his youth by Elordi and by Ciarán Hinds in later years.

Before the war, Dorrigo is engaged to the well-bred but mismatched Ella (Olivia DeJonge), while embarking on a passionate romance with his uncle’s vivacious and “too young” wife, Amy (Odessa Young). Their bond deepens over a Sappho poem, You burn me.

Amy’s influence on Dorrigo goes beyond romance. Kurzel says her memory becomes “part of Dorrigo’s survival”, providing the emotional strength he needs to keep going.

“She’s the thing that allows him to wake up every day, to find some kind of hope,” Kurzel explains. By the 1980s, Dorrigo is a surgeon and reluctant national hero, haunted by survivor’s guilt, and still thinking about Amy.

Dorrigo embodies the kind of man Australians have historically lionised – unreadable, masculine, silent in the face of suffering. Elordi, who speaks softly and solemnly, says he “took what is inherent to the text about him, which is this kind of stoic nature”.

“He keeps his soul deep within him and doesn’t speak too much.”

He tried to understand Dorrigo by looking to Flanagan – and his own father. “Men of a certain time and era are just inherently like that. My father is quite similar to that. For me, it was an interesting investigation into that because I’m not necessarily that kind of man.

“I’m two generations away from it. But I have a lot of those qualities buried in me in certain places. So for me it was an ongoing exploration of self and the men I’ve known in my life, and the men that Richard has written so richly in the text. There was no point where I was like, ‘Ah yes, this is his emotional core, this is who he was’ – it was an ongoing process.”

Elordi and co-star Thomas Weatherall, who broke out in Netflix hit Heartbreak High, spent time with Flanagan, visiting him in Tasmania for hiking expeditions. “He’s a truly wonderful man. The way he tells stories is so rich and detailed. There’s always a profound point, and then you get a follow-up email a week later.”

It wasn’t just emotional grunt work. To truly capture the men’s suffering, Elordi, Weatherall, and the others shed an extraordinary amount of weight. “The bodies were really important,” Kurzel says. “How they disintegrate was a huge part of the narrative, and what those boys looked like against the darkness of the forest.”

The audience watches as the men, once strong, seem to wither – emaciated frames, jutting ribs and hollowed cheeks.

A few days before sitting down with Elordi and Kurzel, I was with a friend whose cousin, Christian Byers, plays one of the POWs in the series. The friend admitted he didn’t know much about the show, but mentioned that in the lead-up to filming, they would go to the pub together where everyone would sink beers with cheerful abandon, while Byers sat glumly in the corner, nursing a plate of steamed greens in a desperate bid to lose weight. At this, both Elordi and Kurzel burst out laughing.

“He was eating?!” Elordi says, mock-scandalised. “That sounds like Christian … I’m surprised he could even make it to the pub.”

For Elordi, the routine was closer to monastic: “Talk to Justin, go to work, shoot, go home, collapse, sleep, intermittently wake up all through the evening thinking about what you’re going to do the next day. Wake up, go in, do it again.”

“It – consumes your whole life,” he says, not unhappily. And is that something he thrives on? “I kind of knew that heading into a Kurzel project. I’ve read stories, so I knew it was going to be all my time, which is how I work anyway.”

Elordi began preparing for the role a year before filming even started. “You want it to consume you because you only have a few months to do this thing and to live in this other world,” he says, pausing. “It’s not as dicky as you become this thing. But you become a part of the ongoing creative process, which is the real magical moment – when your life goes by the wayside and you become this flow. But that to me, just privately, is my greatest joy. There’s no real, like, harrowing weight you carry with you.”

The Narrow Road to the Deep North was inspired by memories of Flanagan’s father, Archie, one of the POWs who survived the ordeal and died just after the author finished his manuscript. “It put an enormous weight on making it,” Kurzel admits.

But the director also has a personal connection to the story: his grandfather was a Rat of Tobruk, and he grew up around him and “this fog of war that existed in his later years” – “I definitely felt kind of what that was as a kid.”

Kurzel adds that films such as Gallipoli and Breaker Morant were his favourites growing up. “They had a huge influence on me. The legacy of war in Australia – what it is and how it’s been portrayed in cinema – was hanging there.”

And while Breaker Morant may have been formative for Kurzel, it was Snowtown – his own hideous breakout about South Australia’s notorious “bodies in barrels” murders – that shaped Elordi.

The Narrow Road is the first major Australian production in which the actor has taken part since becoming an international superstar, but would he really, as he says, have signed on to anything Kurzel sent his way? Absolutely, yes. “He hasn’t made a film that I don’t like.”

“It’s not so reckless when you know what his cinematic sensibility is, and that’s how you judge what your filmmaking experience is going to be. I just knew it was going to be something that I wanted to be a part of. That’s the kind of cinema that I want to contribute to and play in.”

The Narrow Road to the Deep North arrives on Prime Video on April 18.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout