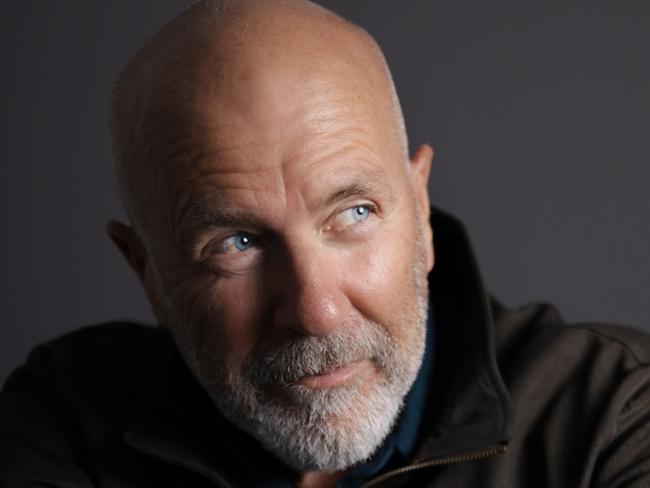

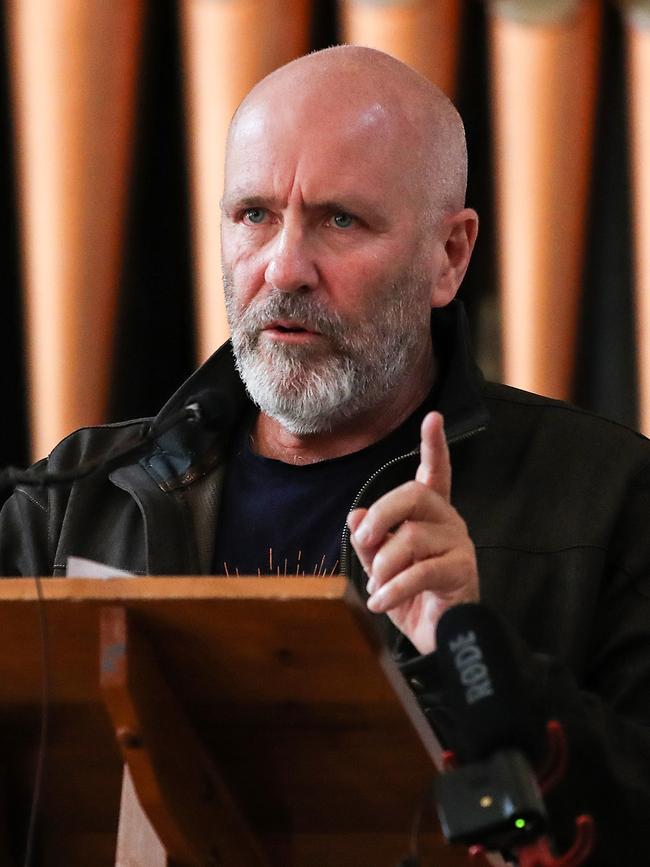

Booker Prize winner Richard Flanagan asks hard questions of his own life

Booker prize winner Richard Flanagan conducts a radical experiment with his new book, Question 7.

How should we think about the radical experiment that is Richard Flanagan’s new book? Imagine the Tasmanian author’s body of work to date as a many-coloured coat, a shimmering patchwork of story. With Question 7 that coat is turned inside out so that the old, familiar patterns are reversed. We can still make out images from theses fictions, though against a darker backing, while the invisible seams of each narrative now appear as a map of tiny stitches.

Question 7 is many things – a defence of literature, a meditation on violence in human history, a complex account of filial piety, a prose-poem sung for the author’s home island – but first and foremost it is an effort to construct narrative from reality instead of imagination, to make something shapely out of the real.

This doesn’t make Question 7 an autofiction, that currently popular yet uneasy mashup of fiction and autobiography that Flanagan has, in the past, expressed reservations about. It is closer to a non-fiction novel, a literary form in which details about the world are arranged with the conscious care and craftsmanship of a creative writer: someone for whom the way one says a thing is as important as the sense those words impart.

The narrative opens in 2012, in Japan, with a description of the author’s travels to research his father’s experience as an Australian prisoner of war during World War II – the story told in Flanagan’s best-known novel, the Booker prizewinning Narrow Road to the Deep North.

But no sooner has Flanagan established the contours of memoir than he swerves into an account of the detonation of the atom bomb over Hiroshima in 1945. The tens of thousands of civilians killed that day, along with those at Nagasaki soon afterward, obliged Japan to surrender instead of fighting to the last.

It was as a result of the Bomb, in other words, that POWs in Japan weren’t murdered as part of scorched earth resistance to an Allied land invasion. Richard Flanagan’s father made it home from war alive thanks to the flight of the Enola Gay – which means the author’s birth 16 years later is premised on destruction of unprecedented scale.

Flanagan will return, again and again, to the moment when a lever was released over Hiroshima, but that particular moral equation remains unsolved.

However restlessly Question 7 travels time and place or experiments with structure and tone, the sustained note here is the discomfort of an author who describes a world filled with information yet devoid of meaning.

If there is any order to such narrative chaos, it emerges from Flanagan’s decision to shape Question 7 according to the same ineluctable laws that govern nuclear fusion. In a daring retrospective swoop, Flanagan describes the dreary London morning in 1933 when the Hungarian polymath Henry Szilard, stopped at traffic lights in Southampton Row, realises in an instant the possibility of a nuclear chain reaction.

Such reactions, Szilard intuits, could revolutionise the production of energy – and form the basis of immensely destructive weapons. What makes Szilard’s world-changing insight even more remarkable is that the imaginative possibility was first granted to the scientist by a novel: H.G. Well’s “scientific romance” of 1914, The World Set Free, which anticipates nuclear weapons the size of footballs, capable of levelling half a city if dropped from above. Flanagan also takes us to the creative genesis of that fiction and finds a work partly inspired by the passionate beginnings of Wells’s affair with fellow writer Rebecca West, an all too human conflagration.

Question 7 is both driven and shaped by a an awed, appalled, sense of the ramifications of human action – that a kiss stolen in an Edwardian parlour could lead to Hiroshima – but it is also fascinated by the ways in which rational and material accounts of the world prove inadequate to tackling such truths. Thus the significance of the book’s title, taken from a story by Chekhov, in which a parody of a children’s math problem is proffered:

“Wednesday, June 17, 1881, a train had to leave station A at 3a.m. in order to reach station B at 11 p.m.; just as the train was about to depart, however, an order came that the train had to reach station B by 7 p.m. Who loves longer, a man or a woman?”

By returning to the non-fiction backing of his novels in these pages – giving “true” accounts of meetings, for example, with some of the elderly prison guards who tortured his father from Narrow Road, or returning to the author’s near-death experience trapped in a kayak on a Gordon River rapid (a far more traumatising reality than the fictional version in Death of a River Guide) – Flanagan furnishes readers with an autobiographical key to his oeuvre.

But he also argues, using these same means, for fiction’s equal standing in the creation of that shared consensual hallucination we call reality.

Geordie Williamson has been chief literary critic of The Australian since 2008.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout