Year of living Beethoven

Two-hundred and fifty years since his birth, the deaf composer still speaks to a universal humanity, but with a new intensity that was previously unknown in music.

Xian Zhang learned to play the piano on an instrument built by her father. It was the mid-1970s in Beijing, the time of the Cultural Revolution when the Communist Party was stamping out the decadent influence of Western art. Classical music — the music of Bach, Mozart and Beethoven — was forbidden.

Zhang’s father worked in a factory that made string instruments, but somehow he was able to find enough of the component parts — including machine-made hammers and keys — to assemble a small upright piano.

“It was the end of the Cultural Revolution, when all Western musical instruments were burned, destroyed,” Zhang says. “Nobody should have kept a private instrument. So that was my parents’ solution to get me one, to get me started.

“The policy was getting a little bit looser, and they really wished that I would have a chance to learn music — my parents were my first teachers, too.”

Like so many music students around the world, Zhang studied Beethoven: simple pieces to begin with, such as the little bagatelle Fur Elise, and then the easier piano sonatas. Later, at Beijing’s Central Conservatory, she pored over the scores of Beethoven’s nine symphonies. Now a conductor on the world stage, Zhang recently has been appointed principal guest conductor of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra. In Melbourne in November, she’ll be conducting Beethoven’s Choral symphony, with its great hymn to humanity, the Ode to Joy.

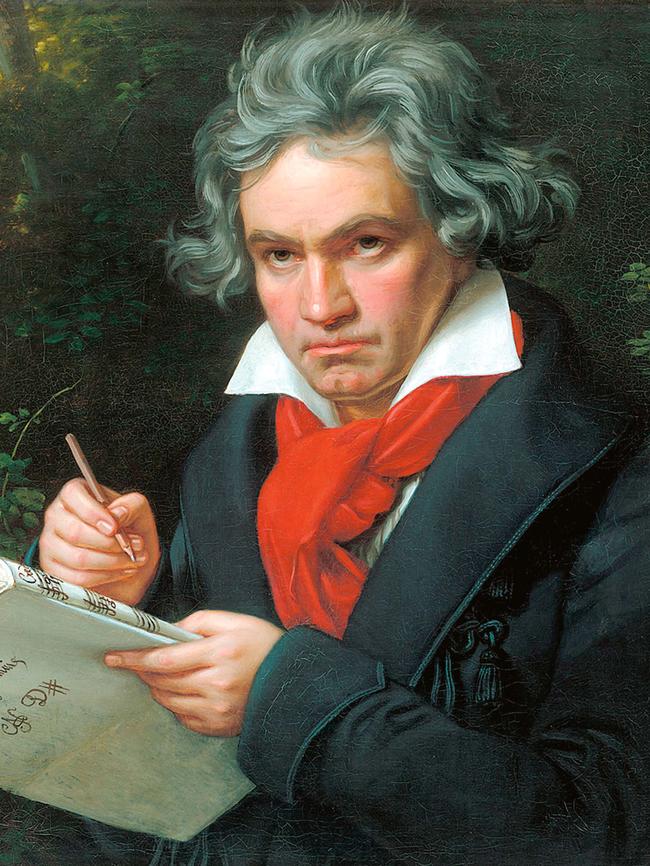

It would be unfair to load on Zhang’s shoulders the global industry that is Beethoven’s 250th anniversary this year. Ludwig van Beethoven, born in Bonn and baptised on December 17, 1770, will be honoured with myriad performances of his piano sonatas, chamber music, concertos and symphonies. His music will be interpreted in dance, echoed in tributes by modern composers, and co-opted for causes such as climate action.

And yet Zhang’s story helps explain why Beethoven’s music is being celebrated so widely and abundantly. Like Bach and Mozart before him, he speaks to a universal humanity, but with a new intensity that was previously unknown in music. We hear it in the gigantic wrestle with God that is the Missa Solemnis. It’s there in the soul-baring moments of his late string quartets. And it’s there in the famous opening motif of the fifth symphony, so aptly described as the sound of Fate knocking on the door — and refusing to leave.

Zhang recalls the first time she conducted the Ode to Joy. Her teacher at the Central Conservatory, Mr Yu, had asked her to rehearse the chorus in preparation for a concert that he was to give of the ninth symphony. Apart from being terrified at the prospect of marshalling 100 singers, the combined effect of their voices hit her like a tidal wave.

“My first contact with the volume and body of voices coming from that huge chorus was overwhelming,” she says. “It’s the power of human beings using our voices and coming together, and that is really the spirit of the piece, the strongest message of the symphony.”

Other leading musicians have had similar experiences with Beethoven. Such is the force of his musical personality that first encounters with him can be as shocking as they are thrilling and life-changing.

Conductor Simone Young, when she was growing up in Sydney, was a cultural omnivore who devoured the collected works of Shakespeare and Dickens as well as Beethoven’s piano sonatas. Her earliest experience of Beethoven’s music was in a piano primer for beginners, which included the melody of the slow movement from the seventh symphony.

Young, recently named chief conductor of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra from 2022, will this year conduct the seventh with that orchestra. In its orchestral version, the Allegretto movement begins with a simple, repetitive melody that grows in stature and volume — the effect of an unstoppable crescendo.

When Young first encountered the piece and played on the piano its insistent, step-like tune, it gave her the creeps. Recently, she found the copy of her childhood piano book, and found that she had marked the page with a pencilled cross — indicating to her teacher, Sister Cecilia, that she’d already studied the piece.

“There was something I found deeply disturbing about that music that, at age five, I put a cross on it, so I wouldn’t have to play it,” she says.

Beethoven is never far from the playlists of symphony orchestras, choruses, string quartets, trios, concert pianists, cellists and violinists. Only groups that are dedicated to repertoire other than the mainstream of classical music — such as specialist baroque or contemporary ensembles — have reason not to play him.

For the past five years, composer Ian Whitney has analysed the (typically low) rate of Australian music performed by the state orchestras and other groups. This year he’s turned his attention to the “bad boy from Bonn”. Indeed, in 2020, Beethoven is pretty much unavoidable.

Richard Tognetti’s Australian Chamber Orchestra is known for its adventurous and eclectic programs, including contemporary music. This year, his orchestra has the highest concentration of Beethoven among the leading music groups. In Whitney’s calculation, almost a quarter, 23.5 per cent, of the ACO’s 2020 performances is Beethoven, starting with an east coast concert tour of the first three symphonies. (The ACO will be augmented with extra players for Beethoven’s breakthrough romantic symphony, the Eroica.)

The West Australian Symphony Orchestra — with a cycle of the five piano concertos, the Missa Solemnis and a concert version of Beethoven’s only opera, Fidelio, among performances of other works — clocks in at 20.3 per cent Beethoven. The Adelaide Symphony Orchestra, where Mark Wigglesworth is conducting a cycle of the nine symphonies, has a Ludwig factor of 13.6 per cent.

Beethoven last year was named the nation’s favourite composer in ABC Classic’s annual listener poll, but even the most fervent devotee may find wall-to-wall Beethoven a Kreutzer too far. Many concert organisers are taking a novel approach to the composer’s music, with the promise that well-known compositions will be illuminated with fresh insights.

WASO’s concert performances of Fidelio, for example, have replaced the opera’s spoken dialogue with a new text by playwright Alison Croggon, to be read on stage by Eryn Jean Norvill. Expect Croggon to give renewed impetus to this rescue opera, in which a woman in disguise as “Fidelio” — fidelity — saves her husband from execution as a political prisoner.

The Australian National Academy of Music in Melbourne is presenting a cycle of Beethoven’s 16 string quartets, performed within a specially made, pop-up concert hall. The Quartetthaus seats only 52 people, with the four musicians seated on a stage that, almost imperceptibly at first, slowly revolves during the performance. Chamber music is made for intimate spaces like this — no seat is more than two metres from the stage — and the revolve allows those in the audience to watch, from different angles, the concentrated interplay between musicians that is such a feature of this genre.

Some performances put Beethoven’s music in contexts the composer surely never imagined. He was born in the same year, 1770, in which James Cook claimed Australia’s east coast for the British crown. That accident of history will reverberate across the intervening quarter-millennium when Beethoven’s Choral symphony is performed by the Sydney Symphony Orchestra with (as yet unspecified) contributions from indigenous elders. Marin Alsop will conduct the concert, called A Global Ode to Joy, as part of an international project on five continents supported by Carnegie Hall’s Weill Music Institute.

The Melbourne Symphony Orchestra is participating in another global initiative, the Pastoral Project, that links Beethoven’s sixth symphony, the Pastoral, with sustainable development and the aims of the Paris Agreement to minimise global warming. The MSO concert on June 5 — World Environment Day — was to have been conducted by Vladimir Ashkenazy, before the shock announcement of the 82-year-old’s retirement last month.

Other performances will introduce choreography or acrobatics where Beethoven never imagined it. The MSO has invited Brisbane’s contemporary circus, Circa, to collaborate on its performances this month of the ninth symphony, prefaced with a new commission from indigenous composer Deborah Cheetham called Dutala, star filled sky.

And the Adelaide Festival is bringing out the Lyon Opera Ballet with a triple bill of contemporary dance works that take as their unlikely inspiration one of Beethoven’s knottiest compositions, the Grosse Fugue. The “big fugue” was originally the final movement of String Quartet No 13 in B flat, but the publisher deemed it so esoteric that he demanded Beethoven replace it with a new ending. Three choreographers have made dances to the fugue’s interlocking parts and relentless dotted rhythms — Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker (in 1992), Maguy Marin (2001) and Lucinda Childs (2016) — and their pieces have been brought together under the title Trois Grandes Fugues.

For composers, Beethoven is an impossible figure to ignore. With the exception of opera, he revolutionised music in almost every genre of the early 19th century. The symphony was a standard four-movement work of classical proportions in the model of Mozart and Haydn until Beethoven tore up the rulebook and, with the Eroica, remade the symphony a kind of psychological quest.

A virtuoso at the piano, before deafness destroyed his career as a performing musician, Beethoven so thoroughly reinvented the possibilities of the still-new instrument that his set of 32 piano sonatas would be called the “New Testament” of keyboard music (the “Old Testament” being the 48 preludes and fugues of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, written for harpsichord). Before Schubert and Schumann produced their magisterial song-cycles, Beethoven produced what is acknowledged as the first major contribution to the genre, An die ferne Geliebte — the “Distant Beloved” of the title sometimes thought to be same as Beethoven’s mysterious “Immortal Beloved”.

It’s not only the grandeur, intimacy and sturm und drang of Beethoven’s music that continues to inspire. Musicians and artists of other stripes respond to him as the archetypal romantic artist: courageous, inspired, uncompromising, proud, suffering, and a little bit mad. He reveals himself in his music, without question, but also in the astonishing document that is the Heiligenstadt Testament. Aware of his worsening deafness, Beethoven wrote from Heiligenstadt a letter to his brothers in which he despairs at his hearing loss. So acute was his social isolation, so grave the impediment to his livelihood as a professional musician, and so diminished his enjoyment of simple pleasures — whether the sound of a flute, or a shepherd’s song — that he was brought to the brink of suicide. But wait — “It was only my art that held me back”.

Had Beethoven killed himself in Heiligenstadt in 1802, when he was 31, we would never have had the glories of the Eroica or Choral symphonies; there would be no Emperor concerto, Razumovsky quartets, or Archduke piano trio; the Appassionata and Hammerklavier piano sonatas would be forever unknown. Having refused death, Beethoven revealed himself as a new kind of creative spirit: the artist as hero.

And he is a hero, still.

Australia’s foremost living composer, Brett Dean, keeps a facsimile copy of the Heiligenstadt Testament on the wall of his flat in London, where he now lives. He regards the document as a talisman, a powerful statement of artistic will.

“It’s hard to know how serious he was about ending it all — there’s a huge amount of ego there,” Dean says. “He knew that he was different, he knew that he was one of a kind. He somehow was able to harness those ideas and energy, to ensure that he didn’t end it all and keep going. He knew that he was onto something special.”

The crisis of Heiligenstadt inspired Dean to write his own composition, Testament, that was originally for the 12 violas of the Berlin Philharmonic — Dean, a viola player, was formerly among their number — and later reworked for chamber orchestra. In it, he directs the string players to play without rosin on their bows, producing a sound that’s not fully present, a “sonic metaphor” for Beethoven’s hearing loss.

Testament will be performed in its chamber orchestra version at the Adelaide Festival in a program called The Sound of History. Dean and the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra are to be joined by Cambridge historian Christopher Clark, who will discuss the social and political currents swirling around Europe in the early 19th century, the time of Beethoven’s Heiligenstadt Testament and Eroica symphony. (Beethoven had dedicated the Eroica to Napoleon before the little corporal had himself crowned emperor, and Beethoven scratched out the tribute in disgust.)

In another busy year for Dean, he is writing a Diabelli variation for Austrian pianist Rudolf Buchbinder — adding to Beethoven’s set of 33 variations on the waltz theme — and also a Beethoven-inspired piano concerto for Jonathan Biss. “So this Beethoven chap keeps following me,” Dean says.

Beethoven was a composer mainly of instrumental music who worked with conventional musical forms — symphony, sonata, concerto — even as he pushed them into ever-more challenging directions. Towards the end of his life, he embraced the chorus — symbol of the collective voice of humanity — and harnessed its power to two of his greatest compositions.

His Missa Solemnis is a setting of the ordinary mass but on a vast scale: a symphonic work for the concert hall, rather than the church. And in the ninth symphony, he broke the norms of symphonic music to include a long fourth movement for chorus and orchestra, a setting of Schiller’s poem, An die Freude, Ode to Joy. It’s as if the orchestra on its own was no longer sufficient to say what Beethoven needed to say, hence the tenor’s declaration when he introduces the singing: “Friends, no more these sounds: let’s have something more joyful.” Enter the chorus.

The Sydney Philharmonia Choir is marking its centenary this year, and will sing both the Choral symphony and the Missa Solemnis in concert with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra. The choir’s artistic director, Brett Weymark, thinks of the mass and the symphony as Beethoven’s “yin and yang”, or the sacred and secular sides of his personality.

“In the Missa Solemnis you hear Beethoven struggling with the idea of an authoritarian God, and when you get to Schiller’s text in the ninth, you have a loving God,” Weymark says.

“The Missa Solemnis in a funny sort of way has always sounded like an animal trapped in a cage: he thrashes at the doors of theology to try and work out what it means. It is a raving sermon from the pulpit.”

Both pieces are extremely difficult to sing. The sopranos and the tenors are high and exposed. The musical lines are complicated and overlapping. Beethoven, who stared down death, who knew the torment of existential despair, who knew that the human spirit can fly on wings of music, does not let his chorus go without a struggle. But the joy, when it comes, is radiant, victorious and universal. That’s why Beethoven is the most beloved of the great composers. It’s why we need him more than ever.