The Tasmanian artworks of Lloyd Rees brought him belated success

Lloyd Rees was ignored for most of his career. Now, the painter’s Tasmanian landscapes are on show in this fine exhibition.

One of the most common myths about artists is that they are not appreciated until after their death. This idea seems to have arisen largely from a misunderstanding of Vincent van Gogh’s career: in fact he did not paint masterpieces for years while the world stubbornly ignored him; he produced almost all the works we now admire so much in the last 2½ years of his life while he was living in isolation in the south of France. And in fact as soon as these works were exhibited, in the last months of his life, they met with a favourable reception.

In a longer perspective of art history, it is very rare for great artists not to be recognised. There are virtually no stories of significant artists in the early modern period whose ability was not promptly acknowledged by their contemporaries. In fact stories of the early manifestation and recognition of genius become a regular feature of Renaissance and baroque artist biographies. Even when Caravaggio had a couple of works rejected by commissioners, no one was in doubt of his outstanding talent, and his Death of the Virgin, for example, was instantly snapped up for a princely collection.

Things became more confused with the advent of modernist styles, from impressionism onwards; but at most the unfamiliarity of new ways of painting delayed commercial success by a few years. Claude Monet was poor in his youth, but wealthy in the second half of his life. Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse did not languish in obscurity; the American post-war abstractionists were eagerly embraced and promoted.

The reality across the past 100 years is that the art establishment and audiences for art rapidly came to identify novelty with quality and to follow fashions in art as slavishly as they followed fashions in hemlines. The perverse result of this passion for safety in numbers – Charles Baudelaire was prescient in seeing that “avant-garde” was the slogan of the follower, not the leader – was that they lost the ability to identify and recognise talent. Instead, like the people who run our big public galleries, they all collect from the same shopping list, based on stylistic and ideological fashions.

And so we have, after all, ended up with unrecognised or underappreciated artists over the past century and at the present day, but these are no longer, as in the persistent myth, brave avant-gardists cruelly ignored by a conservative establishment. There is no longer an avant-garde in the great Westfields of contemporary art, and the establishment lives in dread of missing the latest trend or being outdone in virtue signalling.

The artists who are ignored today, and those who are in fact truly countercultural in our present circumstances, are the men and women who ignore fashion and endeavour to master the techniques of their craft and to renew tradition.

The only hope these people have of being eventually recognised by the obtuse and timid functionaries of the art world is to outlive the cycles of fashion. This is what happened with Jeffrey Smart, largely overlooked in the heyday of abstraction, and belatedly discovered to have been more interesting than most of those stubbornly collected by our museums for decades. Something similar happened with Margaret Olley who, though not as substantial as Smart, eventually came to be seen as a living national treasure in her old age.

Lloyd Rees (1895-1988) is another example of the same pattern: an artist ignored for most of his life as clearly an arch-conservative, but belatedly rediscovered, in part thanks to a connection with Brett Whiteley, and then finally, in his 80s and early 90s, celebrated as a visionary.

Rees grew up in Brisbane, where his exceptional talent was clear from his teenage years before World War II. He became a commercial artist in 1917 and moved to Sydney, where he worked for advertising firm Smith & Julius. This was a business owned by Sydney Ure Smith, one of the most important figures in Australian art between the wars. He was himself one of the finest etchers of his time; he was the publisher of Art in Australia, the most important art publication in the country, as well as of The Home, which also carried extensive coverage of art and design. And several artists of the period, including Roland Wakelin and others as well as Rees, earned their bread and butter at Smith & Julius.

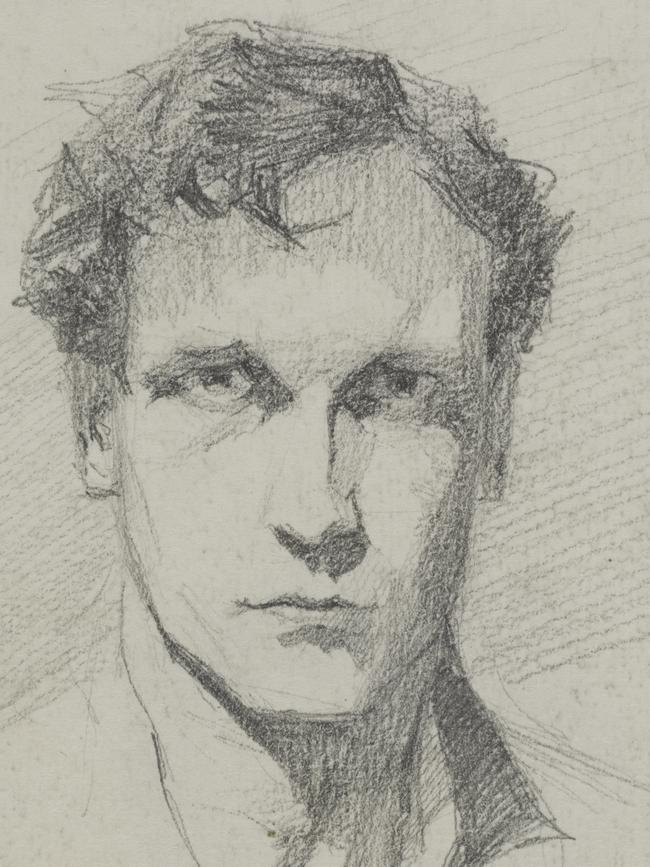

Rees was engaged to Daphne Mayo, who went on to become a distinguished sculptor, in the early 1920s and the two travelled to Rome together. She broke off the engagement in 1925 to devote herself to her work; they remained friends and her bust of the artist in bronze, modelled in 1944, is included in the exhibition.

Rees married Winifred Metcalfe in 1926, but she died the following year giving birth to a stillborn child. He was intensely distressed and suffered a nervous breakdown. Eventually he married Marjory Pollard in 1931, and they lived together until she died in 1988, not long before his own death at the end of the same year.

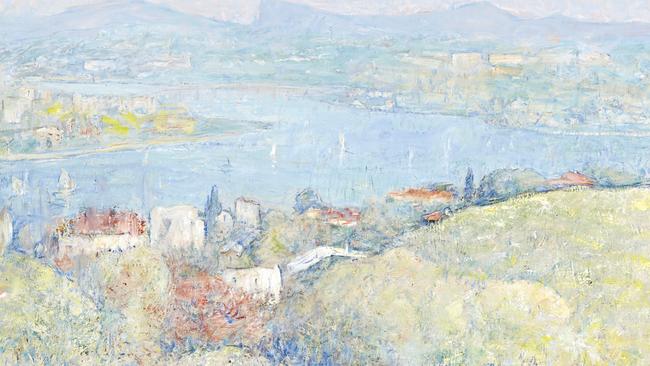

In 1967 their son Alan Rees became the librarian of the University of Tasmania and moved to Hobart, and this led to regular visits and to many paintings of the Derwent River and other Tasmanian scenes; in 1986, already very advanced in years, Rees and his wife finally left the home in Northwood that he had designed himself and moved to Hobart.

It was from the late 1960s that Rees began to be rediscovered as an elder figure of Australian art; the Art Gallery of NSW held a Rees retrospective in 1969, curated by Renee Free, and in 1986 Lou Klepac published Lloyd Rees: Etchings and Lithographs, by Hendrik Kolenberg.

So Rees was not only celebrated late, but it was especially his later work and indeed in many cases his Tasmanian paintings that were admired – thus justifying the perspective of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery’s fine exhibition, curated by Peter Hughes and accompanied by a thorough and useful catalogue including essays by the curator and also a memoir by the artist’s son.

The works that became particularly well known at the end of the artist’s life were the luminous views of light and water, ultimately inspired by his early admiration for JMW Turner but specifically painted at Northwood or in Tasmania. Much was made of the mystical and visionary quality of these pictures, made by an artist whose eyesight was failing in old age; for some commentators it seemed that the quasi-abstraction of these paintings was what redeemed the artist and allowed them to admire him at last.

These same writers would have much greater difficulty with the extraordinary and, at first sight, utterly different pencil drawings that Rees executed in the early 1930s around Sydney Harbour. For those who hadn’t seen them before, these were a revelation in Kolenberg’s retrospective at the Art Gallery of NSW in 2013, and they were the subject of a special exhibition at the Museum of Sydney in 2016, significantly titled Painting with Pencil and accompanied by a beautiful catalogue.

These drawings, executed in the most precise and some might even say pedestrian of media, the graphite pencil, are at first sight the antithesis of abstraction or even of free and painterly expressionism. But in their absolute focus and their sense of complete presence they transcend any simplistic idea of straightforward naturalism. In Rees’s hands the pencil becomes a medium for communing with the very being of the ancient figs and other living or architectural motifs.

We understand why these drawings are so effective when we examine them closely and when we are aware of the materials he was using. As a label in the exhibition reminds us, Rees used only 2B and 3B pencils, the darker and softer ones with a higher proportion of graphite and a lower proportion of clay; he sharpened these to a very fine point and worked with the edge, not the end of that point.

There are thus no lines, or very few, in his drawings; what appear to be contours are in reality boundaries between areas of light and dark, carefully built up by minutely accurate shading with the side of the pencil point. And this is why, despite what looks to the careless eye like microscopic rendering of appearances, Rees’s drawings remain open and suggestive rather than hard and tightly defined, just as Leonardo progressively abolished finite outlines in his drawing and painting.

This phenomenon can be seen in the drawings of this period in the Hobart exhibition, but also even in the very earliest drawings that Rees did as a teenager from photographs of architecture: even at this early date there are no lines; form is defined negatively, so to speak, through the use of shadow. The same is true of the elaborate architectural drawings of later years.

And this becomes particularly significant when we look at what are perhaps the most interesting pictures in the exhibition, and some of the most mysterious: his drawings and paintings of rocks.

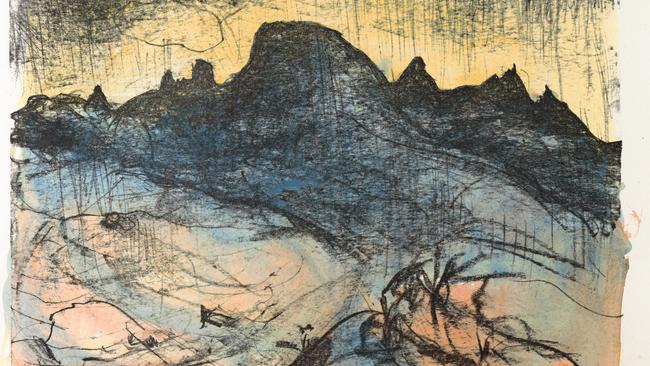

Among the most impressive pictures in the exhibition are the pencil drawing Rocks at North Sydney (1934), the curiously titled oil painting Portrait of Some Rocks (1948), the pen, ink and watercolour drawing The Summit, Mount Wellington (1973), the soft-ground etching A Tasmanian Mountain (1977) and the lithograph Southern Peaks, Tasmania I (1982), represented both in the original black and white and in a hand-coloured version.

In all of these motifs, Rees seems to sense the primal resonance of objects that evoke the unimaginable depths of geological time; whose form is the result not only of immeasurable aeons of accretion but of millions of years of subsequent tectonic motion, seismic violence and the endless weathering of wind and rain; and whose appearance within the artist’s experience is determined by the ever-shifting angle of the sun that illuminates them.

There is thus nothing in our experience more ancient, enduring or perennial, yet even their being is elusive when we try to grasp it; the pencil drawing is wonderfully subtle and precise, but we also see that it is a set of graphite marks on the paper; the ink drawing vividly evokes a silent rocky mass that has stood unchanged through the whole of the existence of mankind, yet there are passages that we also recognise as lines and splashes of black ink.

And even in the large Portrait of Some Rocks, where the motifs are rendered in a masterful combination of form and oil paint, we are struck simultaneously by the presence of the objects and the artifice of paint that has evoked that presence.

Rees’s rocks, no less than his mystical visions of light, remind us that being itself is mysterious, ineffable and ultimately indeterminate.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout