Written application revealed in manuscript exhibition's treasures

THE National Library of Australia's exhibition of manuscripts is full of exquisite treasures - just ignore the inane comments of other visitors.

FELLOW visitors to galleries can be annoying in so many ways. Some people feel compelled to announce in a firm and even emphatic way to their companions that they like a particular picture: not that it is interesting or striking or beautiful, but that they like it, a tacit demand for agreement.

It's even worse when they declare that they like it for some reason that is completely inappropriate or just wrong. I overheard a woman assuring her friend in the NGA Renaissance exhibition that she loved one portrait because its background was abstract when it was simply unfinished.

The remarkable exhibition of manuscripts from the Berlin Library offers some very specific opportunities for visitors to irritate each other, since by its very nature the show demands the viewer's undistracted attention. The most obvious is when someone tries to read the texts aloud to their companion, although the annoyance in this case is in inverse proportion to the erudition of the reader. Much worse are those who earnestly inform their friends of the information they have just learnt from glancing at the explanatory label. Worst of all is making loud and irrelevant observations about the period, the author or the handwriting.

It is worth taking these annoyances in one's stride, though, because the exhibition is full of treasures, from medieval illuminations to modern autographs, with a whole section devoted to musical manuscripts, in which those with a greater knowledge of music than I possess can ponder the relation between the musical sensibility of a composer and the hand - rapid and summary or minutely precise - in which he notates his musical creations.

The main body of the manuscripts exhibited here comes from the collection assembled by Ludwig Darmstedter (1846-1927), a chemist and historian of science who made a considerable fortune by inventing the process for extracting lanolin from wool. This allowed him to pursue his passion for manuscripts, including literary ones, but with a particular interest in documents relating to the history of science. Darmstedter eventually acquired more than 190,000 manuscripts, which he gave to the Berlin Staatsbibliothek in 1907.

From this vast collection, a selection has been made and complemented with additional works, especially in the earliest period of manuscripts and incunabula. There are 100 items altogether in the exhibition, a considerable number when you consider the time needed to absorb any one of them properly. For this reason it is especially useful that the manuscripts are reproduced in a comprehensive catalogue with full entries dealing with the individual and the circumstances of the piece of writing; some pieces, especially in foreign languages, need to be examined at leisure, perhaps with a magnifying glass and dictionary.

The earliest works in the exhibition are medieval manuscripts, but the oldest item is not, as one might expect, a religious text. It is a precious Carolingian parchment of the Aeneid -- a passage from Book IV in which Dido reproaches the departing Aeneas and he replies rather coldly that his destiny is elsewhere, and that their lovemaking did not amount to the marriage she took it for - written in an early form of the simplified hand called Carolingian minuscule.

More than 11 centuries old and still in excellent condition, this sheet reminds us how durable written documents can be, while also vulnerable to fire, flood and other vicissitudes. Parchment, made from sheep or goat skins, is tougher than the papyrus used earlier in antiquity, particularly more resistant to damp conditions. Early paper was also very stable, unlike the acidic papers of the industrial age, which become brittle and discoloured with age. Even today in the age of digital records, we are confronted with the disquieting thought that our files are vulnerable to electromagnetic accidents.

The next group of manuscripts is from the 13th century, leaving behind the barbarian invasions and the struggle for survival that followed the age of Charlemagne, at the height of medieval civilisation in the gothic period. A little later is the first page of the Purgatorio, from a couple of decades after Dante's death. The historiated initial P contains a picture of the poet with an incongruously bearded Virgil as his guide, looking out at a sailing boat -- a literal illustration of the opening metaphor, per correr miglior acqua alza le vele / omai la navicella del mio ingegno: "to run on better waters the ship of my mind raises now its sails".

There are bibles, books of hours, the Codex of Justinian and countless other fascinating things in this early section, including a tabulation of hand signs for counting devised by the Venerable Bede (in which, oddly enough, the number one is signified by the upheld palm with only the little finger bent). There is also a diagram of the human figure overlaid with the 12 signs of the zodiac, a common enough image in medieval and Renaissance books, and of fundamental importance to contemporary ideas of medicine, for the stars were held to exert decisive influences over specific parts of the body; this theory was accepted even by the Church, which only condemned the use of astrology for the purposes of divination.

In the next section we enter the different world of the Renaissance, which evolves again as it passes into the 17th century and the heroic age of the Scientific Revolution. From the beginning, though, we find ourselves in a more personal and intellectually critical world than that of the medieval mind, which tended to be collective, traditional and accretive in its approach to knowledge.

Almost suddenly, it seems - although in reality the transition was more complex - we find ourselves reading individual voices, addressing other individuals; indeed the first document is a letter of apology from Marsilio Ficino to his patron, Lorenzo the Magnificent. We enter here into a world of ideas and personal relationships, of connections and networks of intellectuals that becomes all the more important as the pace of scientific discovery accelerates, and as information and hypotheses are shared in a private manner that avoids potential problems of censorship.

This network has often been called the Republic of Letters, in which the word "letters" is used in the sense of men of letters, not in the sense of messages sent in the mail, although the Republic of Letters was also a fundamentally epistolary system.

Here then, we can read manuscripts by Erasmus, Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo, Descartes and Newton among others - giants who created the scientific foundations of our contemporary world. Each document has its own interest and its own story, from Descartes writing to Mersenne of an argument in Galileo that toute cette proposition est tres fausse - "this whole proposition is quite false" - and to Isaac Newton, informing two acquaintances that he has had them elected as members of the Royal Society, of which he was president.

A broader question worth considering about all these documents is the language in which they were written. The scholarly language of the Middle Ages was Latin, so that there were no language barriers between universities, which were incidentally among the great inventions of the Middle Ages: a young man from Poland or Scotland could attend lectures in Bologna or Paris (where the Latin Quarter owes its name to its Latin-speaking student population at the time).

The Renaissance retained Latin as a scholarly language, and indeed they had no alternative at first, since none of the vernacular languages was yet developed enough to deal with sophisticated intellectual matters. The humanists of the 14th and 15th centuries concentrated on improving the quality of contemporary Latin and purging it of medievalisms, but at the same time the vernaculars were also evolving rapidly as the vehicle for much contemporary literature.

Thus Latin was originally the language of the Republic of Letters, especially between correspondents who did not know each other's native tongues. The Dutch Erasmus writes to the German Fugger in Latin - but Kepler also writes to the Emperor in Latin, although both were German. This began to change with the evolution first of Italian and then of French. Descartes, as we have seen, wrote in French as well as in Latin, and made a particular point of publishing the Discourse on Method in French in 1637.

Certain modern languages began to acquire their own international reach; thus we find Wallenstein, the Catholic military commander in the Thirty Years' War, writing to a French general in Italian which may suggest that it had become, for various reasons, something of a military lingua franca. French too, by the 18th century, became an international language of intellectual exchange, largely superseding Latin except in certain scholarly fields or for particular official purposes.

French was the preferred language of Frederick the Great - a letter to him from Voltaire is included in the exhibition - and had a particular importance among the educated classes of central Europe and Russia. It is interesting to see that Alexander von Humboldt, the German naturalist, accompanies his sketch of a South American monkey with an informal description written in French as well as a technical taxonomic characterisation in Latin.

German was a relatively late developer, in spite of early masterpieces such as Luther's translation of the Bible, and achieved maturity as a modern language in an enormous explosion of creativity around the end of the 18th and the early 19th centuries. After this period, there are many important documents in German, from Schliemann on the discovery of Troy to Kafka apologising to a publisher. By now German was the language of educated people in Prague.

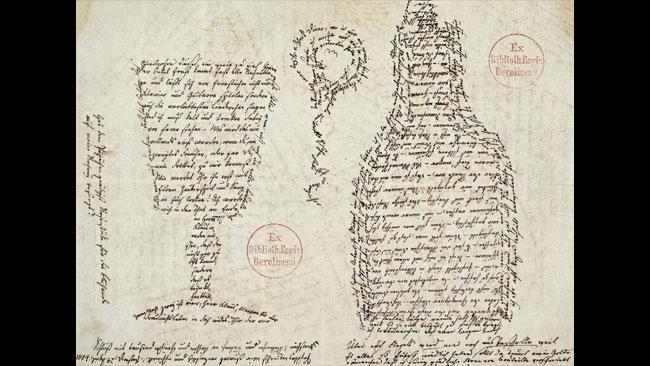

Even in cases where one cannot read the language of the text -- there is a letter by Dostoevsky in Russian -- one of the great interests of the exhibition is in the expressive quality of the handwriting. Hegel, we are hardly surprised to discover, writes in a tiny, dense hand with all letters connected and much underlining; Nietzsche in an open, free hand with space between lines and discontinuities between letters. Simon Bolivar expresses his thoughts in a broad, sweeping script.

Some more mundane things are worthy of consideration, too, such as forms of salutation, always one of the hardest things to get right in foreign languages. There is the recurring theme, as we have seen in passing, of apology: and even when letters are not apologetic in themselves, it is almost a literary convention for them to begin with the expression of regret at the tardiness of a reply. And while some letters speak of great ideas and discoveries, others deal with passing but urgent concerns; the genre is essentially occasional and inherently brings us back to the circumstances of writing.

Handwritten: Ten centuries of manuscript

National Library of Australia, Canberra,

to March 18