Woody’s web of exculpation

Apropos of Nothing is a shocking shrug of a memoir, less concerned with scandal than the affective folderol Woody Allen finds so difficult to understand.

There is a darkness at the heart of Woody Allen. A spoiled, emotionally complacent and selfish man — he states this repeatedly and without compunction throughout Apropos of Nothing, his deceptively casual memoir. He is devoid of insight regarding his own motivations, particularly in relation to the accusations of child abuse levelled at him by his erstwhile lover of 12 years, actress and activist Mia Farrow.

It becomes clear that Allen’s films, among the most brilliantly scripted and innovative yet made, are the celebrated auteur’s attempt to make sense of a world from which he mostly feels alienated. He plays along, but never really belongs.

Apropos of Nothing caused a walkout at Hachette, Allen’s original publisher, and was duly dumped. Staff expressed outrage that Allen had been given a platform even though he was never charged with child abuse of any kind and the evidence remains unconvincing.

As The New York Times reported in 1992, Allen’s adopted daughter and alleged victim, Dylan Farrow, was interviewed nine times by specialists.

Dr John M. Leventhal, head of the hospital team appointed by the Connecticut State Police to investigate her mother’s claims, said Dylan’s statements “contradicted each other and the story she told on a videotape made by Miss Farrow”. These were “not minor inconsistencies … She told us initially that she hadn’t been touched in the vaginal area, and she then told us that she had, then she told us that she hadn’t.”

Allen’s exasperation at what he perceives as Farrow’s hijacking of his story is understandable; the two, like a Hitchcockian take on Abelard and Heloise, will forever be entwined, above and beyond Allen’s colourful life, stellar career (four Academy awards, one Grammy, 10 BAFTAs and so on), and his contented 25-year marriage to Soon-Yi Previn.

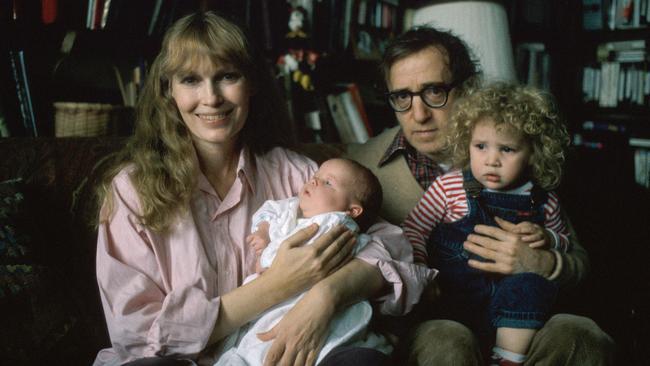

The fulcrum of Farrow’s rage? Allen’s seduction of then-21-year-old psychology major Soon-Yi, Farrow’s adopted daughter. The notorious 1992 Valentine’s card Farrow gave Allen featured a photograph of her family; through each of the children’s hearts, a skewer, and through her own, a knife. An image of Soon-Yi’s face had been taped to the handle.

Farrow’s response to their affair was agonised but also calibrated. By focusing on Allen, she didn’t have to address the far more threatening narrative contained in her daughter’s choice of partner: that Soon-Yi did not like, love or respect Farrow and may have had good reason for doing so.

This narrative brought Farrow’s life choices into question: the multiple husbands, the multiple children (10 adopted, four biological), the strange relationships and marriages, and her astonishing choice to act as a character witness for director Roman Polanski, who in 1977 was arrested and indicted on six counts of criminal behaviour, including drugging and raping a 13-year-old girl.

But in the casting of Allen as a predator, Farrow’s rage was rebranded: no longer cancerous but a manifestation of high maternal value (the lioness protecting her cub).

Later events also call Farrow’s nature, honesty and mothering into question; for example, the claim by Moses Previn, her adopted son, that his adopted sister Tam committed suicide in 2000 after an argument with Farrow, who, in public, stated that Tam had died of “heart problems”; the 2008 death of her adopted daughter Lark from addiction and AIDS-related issues; and the 2016 suicide of her adopted son Thaddeus, who shot himself through the breast.

Bizarrely, the fact three of Farrow’s children have died, in effect, by their own hand is rarely raised by Allen’s detractors, who prefer to focus on his choice of wife. This doggedness almost has a biblical feel. It is as if Allen should be chased with pitchforks and burning torches through newsprint. Whether he is guilty is irrelevant.

It is possible, as has been speculated, that Soon-Yi’s antipathy towards her biological mother was so entrenched that she was unable to connect with Farrow, but it is equally possible that Farrow’s interest in her had always been fundamentally narcissistic.

Allen, too, has never addressed the contempt, conscious and unconscious, towards Farrow that his actions revealed; instead, he praises her “remarkable” beauty, as if that were relevant. Similarly, Farrow’s desire to marry — and conceive with — a “cruel” and “remote” (her words) man without consideration of their baby’s need for a father suggests a self-interest at odds with her public image.

“Mia assured me I could participate in rearing a new child to any extent I cared to,” Allen recalls. “If I wanted to be a hands-on father, great; if not, she’d raise it and I would be the same free soul.”

Farrow, who starred in 13 of Allen’s least interesting films, appeared to be determined to bind herself to Allen at any cost. She could not, he writes, have been “nicer, sweeter, more attentive to my needs. She was not demanding, better informed than me, more cultivated, appropriately libidinous, charming to my friends.” In short, everything was about him.

When she became pregnant, his indifference was pronounced. As Farrow wrote in her 1997 memoir, What Falls Away, he never touched her belly, felt the baby kick or listened to its heartbeat. Despite however many years of exposure, both personal and professional, to this squeamish, precious egotist, Farrow then expressed surprise that Allen appeared “disturbed” by her caesarean scar and by her breastfeeding his only biological child.

Predictably, witnessing a loving maternal-infant dyad had triggered Allen, who remains oblivious to his jealousy of his son. As if reporting aberrant behaviour, he writes, “From his birth, Mia expropriated [Ronan]. She took him into her bedroom, her bed, and insisted on breastfeeding him.”

Such defiance could not be borne by Allen, who, to accommodate his own limited capacities, instructed Farrow to downgrade her intimacy with Ronan. In behaving like a doting mother, she had defected; Allen was no longer the “cynosure” of her attention.

After four or so years of enduring their attachment, Allen became sexually attracted to the more attentive Soon-Yi, who may have reacted with the same affront to her adoptive mother’s preoccupation.

There is also this: even though Allen and Farrow were never married or cohabited, Soon-Yi continues to be ignored and infantilised — by Farrow, her family and by Allen’s detractors — as a “retarded” Korean street child whose ingratitude to her wealthy American saviour is never explicitly stated, only implied. Spanning a quarter of a century, this dismissal of her recollections and opinions is in itself abusive, and the attitude persists.

In response to a 2018 interview with Soon-Yi, one journalist wrote, “And there are more technical facts we must accept: despite their 35-year age difference, there was no rape or incest.”

Well, no more than there was when Farrow, then 19, first slept with 49-year-old Frank Sinatra, her father’s friend whom she later married and, in 2013, validated as the “great love” of her life.

Farrow, as a privileged, willowy and conventionally lovely white 19-year-old, is permitted to have experienced a “great love” for a womaniser twice her age, whereas the 21-year-old Soon-Yi, an unprepossessing short-legged Asian whose mother was “reportedly a prostitute”, is disparaged as having had a “crush” based on a misapprehension.

Soon-Yi’s “warped” marriage has lasted 25 years; Farrow’s “great love” lasted two.

Farrow’s narrative — the same that won her investigative reporter son Ronan a 2018 Pulitzer for his magnificent New Yorker take-down of Harvey Weinstein (another emotionally stunted film mogul) — is that of the patriarchal Jewish lecher and his helpless, mostly Christian, female victims.

In the same vein, the blurb for her adopted daughter Dylan’s novel Hush reads: “How do you speak up in a world where propaganda is a twisted form of magic?”

Moses recalls Farrow “drilling it into our heads like a mantra: Woody was ‘evil,’ ‘a monster,’ ‘the devil,’ and Soon-Yi was ‘dead to us’ … So often did she repeat it that Satchel [told a nanny], ‘My sister is f..king my father.’ He had just turned four.”

Last month, Farrow tweeted a video of Ronan singing Steven Sondheim’s Not While I’m Around, the song she “used to sing to him when he was little”. Much was made of her maternal pride, his artful embarrassment — he has a beautiful voice — and their banter, but no one mentioned the obvious: that the song, from the musical Sweeney Todd and in the context of Allen’s memoir, draws disquieting parallels.

Sung by the opportunistic, duplicitous Mrs Lovett to the orphaned boy she mothers, it goes, “Others can desert you / … Demons’ll charm you / … But / Nothing can harm you / Not while I’m around”. Lovett dreams of marrying the “demon barber” Todd, who is indifferent to her; he still loves his wife, whom Lovett says is dead. When Todd discovers Lovett lied, he kills her, and the orphan she loved avenges her by killing him.

Appropriately, the title of Ronan’s 2019 book is Catch and Kill: Lies, Spies and a Conspiracy to Protect Predators. It was published by Hachette, the company that canned his father’s book.

The most disturbing charges Allen lays against Farrow are that she coached Dylan to lie about the sexual abuse (a possibility raised by at least one specialist, and backed by Moses) and that she had Ronan’s legs broken to conform to her aesthetic ideal.

Allen quotes Moses: “Mia had [Ronan] undergo cosmetic surgery to extend his legs and gain a few inches in height. I told her I couldn’t imagine putting someone through the ordeal for cosmetic reasons. My mother’s response was simple, ‘You need to be tall to have a career in politics.’ ”

The idea that any parent could encourage a healthy child to undergo a surgical procedure as potentially dangerous and agonising as leg-lengthening to (vicariously) achieve her political ambitions is near-incomprehensible.

Attributing his incapacitation to a “bone infection” contracted in Sudan, Ronan has said that he couldn’t wear trousers “for several years because I had these giant metal halos holding my bones together … It ain’t great when you’re trying to live your life and date and be a normal person.”

Photographs appear to support Moses’s allegations. Ronan’s calves seem to be significantly longer than his thighs and oddly disproportionate to his arms, which are those of a short man. If the allegations are true, it means that he risked both life and mobility in an effort to retain maternal approval.

“For all of us, life under my mother’s roof was impossible if you didn’t do exactly what you were told, no matter how questionable the demand,” Moses said.

Publicly, Ronan continues to excoriate his father, but the parallels between his fiance and Allen are staggering. A left-wing Jewish New Yorker and charming stand-up comic, Jon Lovett also shares Allen’s rapid delivery, exaggerated emotionalism, casual attire, homeliness, pallor, dark, rumpled hair and black-rimmed spectacles.

It isn’t difficult to conjecture that marrying a man who looks and sounds like Allen is the only way Ronan will ever be permitted to love his detached father, a man whose ghost he perpetually chases and chastises in the form of others.

Allen, in the end, comes across like a figure in a snow globe: immune to tragedy, uxorious, content in his small, sheltered and predictable universe and protected — not by fame or a sinister cabal of associates, but by his near-Aspergian indifference to the feelings of those he does not love. (In part or entirely, this could be a by-product of ADHD; in the book he mentions taking Adderall.)

Even in his undisputed cinematic genius, Allen remains a miniaturist, mining small stories to big effect, an urban provincial of sorts. His cinematic ambitions long ago plateaued.

Apropos of Nothing is a shocking shrug of a memoir, paradoxically less concerned with scandal than the affective falderal Allen finds so difficult to understand.

Did he molest Dylan? Based on the evidence I’ve read, I do not believe he did, the integrity of #MeToo notwithstanding. The biggest reparation he owes is to Ronan, who, as a direct result of Allen’s narcissism, insensitivity and improvidence, was not only deprived of a father but also was forced prematurely to confront the darkest human suffering through his equally narcissistic mother’s choices.

Antonella Gambotto-Burke’s new book, Apple: Sex, Motherhood and the Recovery of the Feminine, will be published early next year.

Apropos of Nothing

By Woody Allen. Arcade, 400pp, $24.99 (e-book)

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout