William Kentridge, the master of original surprises

WILLIAM Kentridge is anything but the familiar battery hen of the contemporary art business yet he has achieved great acclaim.

IT is almost surprising that William Kentridge - whose work is displayed in an impressive retrospective at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image in Melbourne and a substantial commercial exhibition at Annandale Galleries in Sydney - has achieved the acclaim he now enjoys, because he is anything but the familiar battery hen of the contemporary art business.

But he is proof of a reassuring fact: that even if lucrative careers today can be built on a lack of talent combined with relentless promotion, real ability and originality at some point compel recognition.

It was Kentridge's fortune to be born and grow up in South Africa during the apartheid years, when the country largely was cut off from cultural exchanges with the rest of the world. For this was the time when contemporary art, after the last explosion of modernism in post-war America and then the alternatives of pop cynicism and political engagement in the 1970s, had begun to drift away from civil society to form its own self-contained and self-recycling system known as the art world.

The art business grew exponentially. As art severed its connection with social reality and its content thus became inconsequential, millionaires were able to collect work that was ostensibly radical in one way or another, because such political stances were now no more than charades. I once heard a woman whose husband managed diamond mines in Africa speak of her passion for politically challenging art; whether originating in hypocrisy or stupidity or both, such disconnection is widespread among both private and corporate collectors.

Kentridge developed in an environment in which art was not yet cut off from life and at a time when the tensions of the social fabric that surrounded him, during the apartheid years and the transitional period that followed, were inescapably urgent. They were also complex and could not be reduced to the facile formulas beloved of ideological commentators. Kentridge was on his own, forced to think, and feel, for himself.

Kentridge studied art, but then worked for years in the film industry, which he hated. But in the end the film experience was vitally important, for he discovered, though comparatively late, that he could apply his evident talent for drawing to animation.

Motion quite literally brings the drawings to life: individually, they are solid but workmanlike, always aesthetically interesting but rarely substantial enough to stand on their own as graphic works. But these are the very qualities that lend themselves to highly effective animation: the solidity and unpretentiousness of the individual sketches and the rapidity with which the artist is able to draw them again and again to achieve the effect of filmic movement.

The early films are made using the technique of stop-motion animation: the camera takes a shot of a drawing, then another and so on. But rather than making thousands of separate in-between sketches to achieve the relatively seamless quality of high-production commercial animation -- to say nothing of the slickness of contemporary digital animation -- Kentridge erases and redraws images many times on the same sheet. This is possible with an easily erasable medium such as charcoal, but it leaves a ghostly after-image of each erasure, which undercuts the illusion yet emphasises the idea of movement. The medium is perfectly adapted to the content of the films, which evoke a dreamlike state of consciousness, punctuated by anxiety and apprehension, in a world that is at once all too real and prone to surreal transformation.

In Stereoscope (1999), for example, the figure of a businessman in a chalk-striped suit -- his name is Soho Eckstein, but he is, like the similarly bald stout men in Jeffrey Smart's early work, an alter ego of the artist -- is seen in his office, apparently in command of complex systems and networks of communication and command. But then things start to go subtly wrong; entropy overtakes order, or perhaps grows out of systems that have run out of control. The protagonist is split into twin selves, whose destinies start to diverge: the existence of one becomes crowded to bursting point while the other's becomes a void.

Finally the system itself breaks down and order is replaced by violence and brutality, suggesting both the repression under apartheid (which was abolished in 1994) and the conflicts of ensuing years.

The film evokes the violence in South Africa but never in simplistic or tendentious terms. The nearest it comes to explicit commentary is in the injunction at the end to "give" and to "forgive".

Similarly, Tide Table (2003) shows the same character sitting by a beach in a deckchair, observing children playing and families bathing. From a nearby building, a black generalissimo observes the scene through binoculars. Glimpses of carefree children skimming stones on the water alternate with sinister visions of emaciated cattle or the inside of a clinic, suggesting the plague of AIDS in southern Africa. Meanwhile the shallow waves wash up and down the beach to the foot of Soho's deckchair, their white foam evoked with extraordinary economy and vividness through the inherently abstract medium of charcoal or white chalk.

In another room of the ACMI exhibition, which includes a witty homage (2003) to Georges Melies and his 1902 silent film A Voyage to the Moon, there is a sort of animated self-portrait in which, at first sight, we see the artist drawing a life-size figure of himself and we glimpse the tools of his trade, a charcoal stick and rag. But there is something not right: as he appears to erase the figure, it becomes more fully drawn; and as the film repeats on its loop, we see it begin with Kentridge assembling pieces of torn paper into the whole figure. And then we realise that the whole thing is projected backwards, the original having followed the drawing of the figure to its completion and then destruction; and we understand why the one strangely awkward bit is at the false beginning, when the artist appears to walk into the frame and begin to gather the pieces of the drawing; for he would have had to back out of the frame in the original, and that is hard to do with the same naturalness as walking forward.

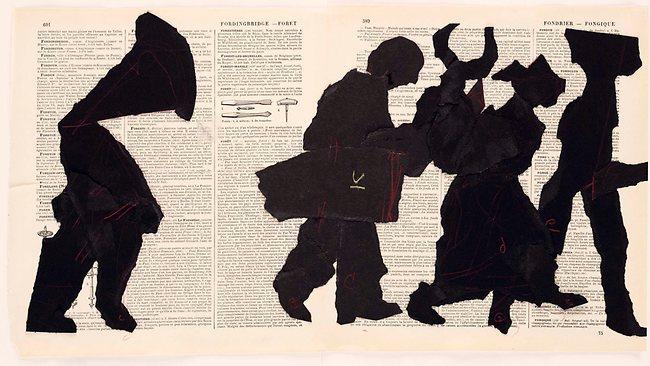

The surreal imagery of the early works becomes more animated and grotesque in the later ones: an ostensibly real world that collapses unexpectedly into the absurd is replaced by an overtly absurd and nightmarish cast of characters who allude obliquely and allegorically rather than directly to the human beings we know. At the same time, as we see in Shadow Procession (1999), displayed in the first room of the exhibition, Kentridge's intuitive approach to his material has led him to discover a pair of powerful and archetypally resonant formal devices, whose conjunction is expressed in the title of the work.

The first of these is the procession. There is probably no more primitive and spontaneous kind of performance than when a group of people form into a line and follow each other - either along a ritually defined pathway or, frequently, simply around in a circle at a cult site - chanting, stamping and moving rhythmically together. A communal bond is formed and the individuals participating are joined in a simple but deeply affecting aesthetic pattern.

The second is the shadow or silhouette, with its associations of fear, memory and dreams: profiles that are only half-recognised without features, or elongated and distorted by anamorphic effects. Kentridge puts these together to make what has become the most distinctive effect of his mature work, the grimly burlesque shadow-march that grinds along with the unrelenting and oppressive animation of a machine. In this amalgam of carnival and shadow-terrors, Kentridge taps into the same archetypal world that gave birth to the Guignol and Punch and Judy puppet shows, and aspects of the commedia dell'arte tradition.

There is something too of the medieval dance of death, the late medieval images in frescoes, illumination and prints of the universality of death, in which monstrous and skeletal figures cavorted with human figures representing all classes and ranks of society.

These reflections on the perennial presence of death thus had social and political implications as well, and so it is with Kentridge's works, among the best of which was a set of films and projections that was the high point of the 2008 Sydney Biennale. They tell of the show trial of Nikolai Bukharin under Stalin in 1937, and while extracts from the transcripts are played on one wall - poignant with the unintentional black humour of small minds engaged in a horror that is far bigger than they are - the various projections evoke an abundance of metaphorical and symbolic commentary, from animated paper cutouts to an anamorphically distorted film of a soldier executing a Cossack dance, and above all the frenetic loop of a danse macabre in which grotesque paper cutouts parody the triumphant parades of Soviet kitsch.

The work is striking because for all its hyperactivity, it is imbued with a deep sense of humanity. The most touching, and yet bitter, moment is when Bukharin appeals in vain to human feeling. His plea is greeted with scorn by his enemies, but it is relevant to all of Kentridge's work, in which a feeling for human beings, both for their confused inner life and their moral and social existences, is never reducible to simplistic political messages. There is a fundamental seriousness to the work, and yet the emphasis is on the pathos of moral predicaments rather than finding villains and directing blame.

There is humanity too in the material form of the work: the improvised and low-tech quality of the films and the cut-out shadow figures, but also the hand-made nature of the drawn images themselves.

They are not digital, not slickly produced, not outsourced to studios. The combination of simplicity, improvisation and poetic conviction in Kentridge's work is spontaneously appealing and shows up the hollowness of a lot of less substantial contemporary product.

The contrast with three new contemporary acquisitions exhibited with some fanfare at the Art Gallery of South Australia is telling: an installation by the Chapman brothers is, unsurprisingly, politically and historically pretentious without being morally serious; a pair of sculptures by Thomas Hirschhorn, intrinsically indifferent and mechanically studded with screws, is simplistic and repetitive; and as for the enormous filmic installation by the "celebrated Russian collective AES+F", it is in every respect the opposite of Kentridge - the quintessence of commercial vacuity, an inane and infinitely complacent celebration of the aesthetic of the advertising industry.

William Kentridge: Five themes

Australian Centre for the Moving Image, Melbourne, to May 27

William Kentridge: Universal Archive (Parts 7-23)

Annandale Galleries, Sydney, to April 21

Correction: In the March 31-April 1 review of the Adelaide Biennial, a drawing by Tom Nicholson after H.J. Johnstone's Evening Shadows and a group of copies after the same picture were wrongly attributed to Jonathan Jones. We apologise for the error.